Sixty years ago this month, TIME named Martin Luther King Jr. 1963’s Man of the Year, making him the first solo Black American to hold the title, which was later renamed Person of the Year. After the March on Washington and King’s iconic, nationally-televised speech, he was a fitting recipient of a title given to the person who had done the most to influence news in the prior year. Through the pages of the feature, readers came to know a King who was imperfect, mercurial, and whose leadership was “more inspirational than administrative.” This King was also extraordinarily human.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

In short, this portrayal sounds nothing like something one would read about King in 2024.

The dichotomy reveals that has King has become mythologized—with major consequences for democracy today. Deifying King creates a contrast between him and social movement leaders in the present. That enables critics to scorn their tactics and deride their movements as being un-King-like.

It also discourages the hard activism necessary to create social change. As Dianne Nash, a founding leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), worried would happen, the public adoration of King leaves Americans waiting for the next transcendent, once-in-a-generation leader to emerge. They don’t understand that the civil rights gains of the 1960s came from years of concerted activism by a cadre of leaders, none of whom lacked flaws or escaped criticism in the moment.

Read more: Don’t Forget That Martin Luther King Jr. Was Once Denounced as an Extremist

Despite the reverence with which King is remembered, he was actually highly divisive during his life. In 1963, only 35% of white Americans had a favorable view of the reverend, a favorability rating that would drop even further in the last years of his life.

Media discussion of King reflected this reality, including the Man of the Year profile.

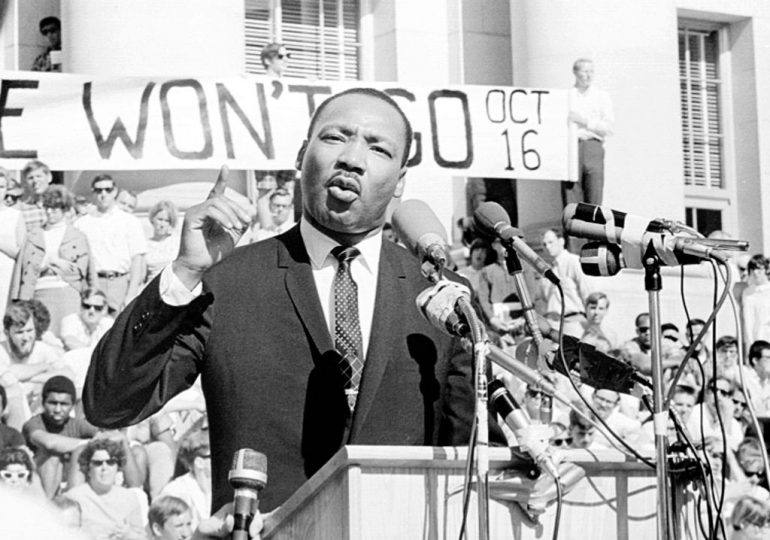

The seven-page Man of the Year feature, titled “America’s Gandhi: Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,” included photos of King in some of the pivotal moments of the Civil Rights struggle, from his arrest in Birmingham in 1963 to his meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Yet the accompanying feature, though largely positive about the civil rights movement, was anything but a hagiography of King himself.

In fact, reporter Marsh Clark conveyed outright skepticism about King’s leadership of the movement. Despite his prominence, King had “neither the quiet brilliance nor the sharp administrative capabilities of the N.A.A.C.P.’s Roy Wilkins.” He also lacked “the sophistication” and experience in dealing with business leaders that could be attributed to the National Urban League’s Whitney Young Jr., as well as “the inventiveness” of CORE’s James Farmer, “the raw militancy” of SNCC’s John Lewis, and “the bristling wit” of author James Baldwin.

Instead, King possessed “a raw-nerved sensitivity that bordered on self-destruction.” Clark described his style as “funeral conservatism.” The civil rights leader had “very little sense of humor” and the use of metaphors in his speeches was “downright embarrassing.” Clark conveyed how King’s “apparent lack of imagination” in plotting the Albany campaign—which ended in failure—had brought him to “his lowest ebb in the Negro movement.”

The portrayal certainly wasn’t all bad. Clark conveyed that King had “an indescribable capacity for empathy that was the touchstone of leadership” and discussed his gift for inspiring the masses. He also recounted King’s firm commitment to non-violence, even as white people reacted brutally to civil rights activism.

Broadly, Clark’s portrayal left open the question of whether King was worthy of being seen as the preeminent force in the civil rights movement.

This skeptical depiction is jarring to modern eyes, but it was consistent with media narratives about King at the time in the North and South alike.

Journalists continually questioned his leadership, substance, and tactics. In a 1963 story about the Birmingham campaign, for example, TIME had described King as “the Negroes’ inspirational but sometimes inept leader.” The Washington Post similarly opened a profile by describing a “considerably less noble and considerably more realistic picture than Dr. King’s public image as the American Gandhi.” It went on to depict the civil rights leader as “inflexible” and a “poor administrator.”

Read more: 10 Historians on What People Still Don’t Know About Martin Luther King Jr.

In addition to questioning his ability, the media, especially but not exclusively in the South, often charged that King was inciting violence, treating his philosophy of nonviolence with skepticism. In one story, the New York Times described King’s plan to take on racism in the North with dubiousness, describing the “inherent contradiction in Dr. King’s summons to Negroes to act ‘peacefully but forcefully to cripple the operations of an oppressive society.’” This coverage damaged King’s legitimacy.

And it wasn’t just King who confronted media scrutiny and skepticism in the early 1960s—it was the entire civil rights movement. News reports described civil rights protesters as “militant,” “outside agitators,” “disruptive,” and “unwise.” For example, in coverage of the nonviolent Birmingham campaign, the Washington Post reported, “Negroes overwhelmed local police officers by sheer force of numbers and swarmed into the downtown area.” This description made the demonstration sound more like an out-of-control mob than a well-organized, peaceful protest.

Newspapers also perpetuated conspiracy theories about alleged communist ties held by King and the movement more broadly. For example, a 1963 Boston Globe article quoted Mississippi Governor Ross R. Barnett alleging civil rights protests were a conspiracy “to divide and conquer our country from within.”

Following TIME’s feature, King shared his gripes about what he perceived to be the article’s low blows with close confidantes, particularly the slights about his sense of style, humorlessness, and embarrassing metaphors.

In public, however, he was gracious, writing to TIME’s co-founder Henry Luce to express his gratitude for the honor—one “to be shared by the millions of courageous people who have been caught up in the gallant spirit of the entire freedom movement, even to offering their bodies as personal sacrifices to achieve the human dignity we all seek.” King also made sure to compliment Clark’s “seriousness of purpose, dedication to his job and skillful ability as an interviewer and writer.”

What explains the great gap between how Clark and other reporters saw King during his life and the mythologized hero celebrated each January?

King’s assassination in 1968 ignited a 15-year battle to create a national holiday commemorating his birthday. While Coretta Scott King and members of the Congressional Black Caucus fought for the federal holiday, conservative white political leaders like Congressman Gene Taylor (R-Mo.), Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), and Congressman John Ashbrook (R-Ohio) continually fought back. This fight laid the groundwork for a process through which the controversial, radical King who fought against the triple evils of racism, militarism, and capitalism disappeared and a whitewashed version of King, palatable to moderates and conservatives, took his place.

The concessions about King’s legacy worked. In 1983, Ronald Reagan begrudgingly signed a bill establishing the celebration of the civil rights leader’s birthday as a national holiday. But the King institutionalized by Reagan, one characterized by colorblindness, individualism, and American exceptionalism, became central to a long, successful campaign of historical revisionism by right-wing conservatives, designed to ensure that Americans would remember a King void of complexity and context.

That is evident from the gap between the depiction of King in the media in the 1960s, and the celebration of him in 2024. That chasm also illustrates how the sanitized understanding of King distorts how Americans understand social movements in the present. By seeing King as the saintly patron of colorblindness and peace, beloved by all, an exceptional hero that the U.S. had not seen before and will never see again, it becomes possible to create a cultural disdain for civil disobedience in the present.

Those opposed to movements like Black Lives Matter can juxtapose social disruption with the “proper” protests of King’s time. When highways are blocked by protesters, when activists fill congressional offices in sit-ins, when protesters rally en masse, many Americans denounce these movements for their “divisive” and disruptive tactics. They contrast these “bad” movements with the “good” King and the civil rights movement.

For example, a recent editorial decried anti-war activists’ disruptive strategies as “the exact opposite” of those taken by King and his colleagues, who used “orderly and utterly peaceful protests to appeal to the better angels of Americans’ souls.”

This revisionist history enables politicians to roll back civil rights gains from voting rights to affirmative action and repress and silence contemporary democratic dissent.

And it’s all based on a distorted perception of the past. The non-violent tactics practiced by King were called into question and faced similar claims in the 1960s.

Resurrecting the contemporary media portrayals of King also reveals that great leaders often are hated, vilified, and characterized as domestic threats. These leaders do not necessarily get star treatment from the media.

Understanding this reality can enable Americans in the present to get more curious about contemporary movements and interrogate feelings of antipathy toward their tactics.

If Americans comprehend that the great leaders of the past were recognizably human, that the idyllic social movements of American nostalgia were once wildly unpopular, they can see that such efforts are not relics of another time. They are still present in the U.S. in 2024. The question is whether Americans can recognize them?

Hajar Yazdiha is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southern California. She is author of the book The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

Leave a comment