On Dec. 9, the U.S. vetoed a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for a “humanitarian ceasefire” in Gaza. While this move was, in one sense, dramatic—the U.S. broke with its allies and cast the sole vote against the resolution—it was also routine. For a half century, the U.S. has used its veto power to halt or delay dozens of resolutions seen as unfavorable to Israel.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

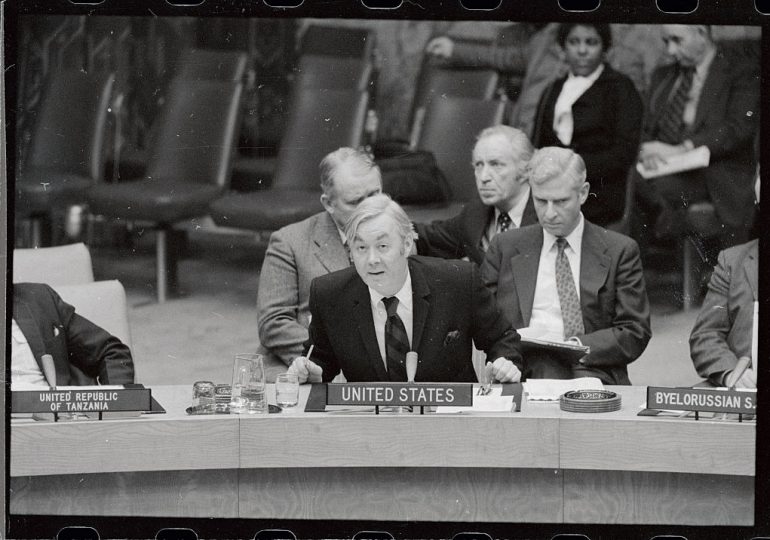

When this practice began in the 1970s, it garnered considerable national attention, with debates roiling the State Department and public alike. One such incident — which landed its key participant, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Daniel Patrick Moynihan, on the cover of TIME magazine — shows how much Americans used to care about how the U.N. viewed Israel and the U.S. and why perhaps they still should.

In 1964, 77 countries from Latin America, Africa, and Asia formed the “Group of 77,” which quickly asserted itself as a majority bloc in the U.N. General Assembly (UNGA). Most of the G-77 shared one of two commonalities: they were either former colonies or were poorer than the industrialized nations of North America and Western Europe. Because of this shared colonial and economic history, the G-77’s agenda initially focused on unraveling the cultural and economic legacies of the imperial age, and shifting political, cultural, and economic power away from the old imperial centers and toward the Group of 77.

This push left the U.S. isolated in the UNGA, and regularly on the losing side of votes. The U.S. faced skepticism from the G-77 countries because of its own history of empire, its alliance with former European colonial powers, and its Cold War anti-communist efforts in places like Vietnam, which seemed to many in the G-77 like empire in a different form. The U.S. and its European allies were also the wealthiest states in the world, and they resisted efforts by the G-77 to rebalance the global economy in its favor. The fissure ran deep: the G-77’s worldview fundamentally contrasted with the U.S.’s vision.

Read More: U.S. Receives Backlash For Vetoing U.N. Resolution Calling for Gaza Ceasefire

As the G-77’s alternative agenda for the UNGA began to manifest itself in the 1970s, it increasingly generated alarm in the U.S. Americans saw their country as a global leader in the fight against tyranny, and they refused to swallow the fact that a majority of governments around the world instead saw the U.S. as a source of tyranny.

For some, like U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, the alarm stemmed from more than wounded feelings. While Kissinger had almost no sympathy for the G-77’s worldview, he worried about the risk the emerging bloc posed to U.S. security and prosperity. The U.S. and its allies had significant advantages in wealth and industrial capacity, but the G-77, potentially in alliance with the Soviet Union, could team up to block U.S. access to critical supplies of raw materials, including oil. This scenario was anything but far-fetched by 1975.

The 1970s represented a new era for the global distribution of power. In 1973, Arab oil producers had implemented an embargo against the U.S. for its support of Israel in that year’s Arab-Israeli War. The embargo, which lasted six months, stood as a stark reminder of the dangerous possibilities of a world united against the U.S. There was, as Kissinger told a group of congressmen in the summer of 1975, “a practical necessity to change the direction we are headed,” and to improve U.S. prestige among G-77 nations. The world appeared to be drifting away from the U.S., a trend which needed to be reversed.

That shaped how Kissinger approached a no-win debate in the UNGA that eventually produced Resolution 3379 on Nov. 10, 1975, arguably the most divisive in the body’s history. It labeled Zionism “a form of racism and racial discrimination,” explicitly linking Israel, and the ideology behind its founding, with European imperialism and white supremacy. They all, the document proclaimed, shared “the same racist structure.”

That the U.S. would oppose the resolution — and that it would pass anyway — was never in question. The debate offered no opportunity for the type of compromise Kissinger was looking for and he hoped to move past it quickly.

For Ambassador Moynihan, however, the resolution was precisely the place to confront the broader changes afoot at the U.N. It would not be through compromise, as Kissinger suggested, but through strident defiance.

In the ambassador’s eyes, 3379 was more than just an attack on Israel’s legitimacy. It was an attack on democracy itself. Where the G-77 saw a foreign population forcibly taking land from Palestinian Arabs with the support of the old imperial powers, Moynihan saw an embattled bastion of democracy surrounded by dictatorial regimes. As he spoke out against the resolution, Moynihan received significant public support in the U.S..

His view resonated with some Americans for ideological reasons — the fact that Israel elected its government while most of its enemies did not — and with others because of race. The latter group saw Israelis, regardless of their actual ancestry, as more like white Americans than their Arab enemies. One writer in National Review noted in 1970, for example, that Israel was among a group of “white enclaves… destined for a crucial role in the history of Western civilization.” All of Moynihan’s supporters believed America’s position in the U.N. mattered and required defending.

As the resolution neared passage, Kissinger instructed Moynihan to tone down the speech he’d deliver in response. Kissinger wanted the U.S. to oppose the resolution, but he also felt that “we can’t have our whole foreign policy revolve around it.”

The ambassador ignored him. Soon after the resolution passed, Moynihan rose and declared: “the United States… does not acknowledge… will not abide by… will never acquiesce in this infamous act.” The resolution, he continued, granted “symbolic amnesty – and more – to the murderers of six million Jews.”

The fiery speech was wildly popular at home. Tens of thousands assembled in Times Square to protest the resolution, while editorials across the country excoriated the vote, and letters poured into the White House condemning the resolution and praising Moynihan. Polls indicated that 70% of Americans supported the ambassador for, as TIME put it, “giving them hell at the UN.”

Read More: How India Became Pro-Israel

Kissinger was furious. Moynihan had ignored his instructions and refused to cut the “symbolic amnesty” line. In response, he began to try to engineer the insubordinate ambassador’s exit. Leaks and counter leaks ensued, and Moynihan resigned in January of 1976, using his time in the U.N. as a foundation for a successful run for Senate that year.

The story was major national news. Americans believed that resolutions passed or not passed in the U.N. were important matters with implications for how the U.S.’s vision of the world was received by other countries. They believed that the U.N. was a reflection of global realities and, if it suggested the U.S. was isolated, that merited either a thoughtful accommodation, or a strenuous response — depending on one’s camp.

This is clearly no longer the case. While the U.S. government’s support for Israel remains a deeply divisive topic, few Americans pay any attention to the U.N. Going it alone, or close to alone, is an expected and accepted reality, one roughly a half century old.

In one respect this is understandable. The U.S. is more than powerful enough to ignore sentiment in the U.N. and proceed in whatever way it thinks is just. Yet, at the same time, the U.S. positions itself as a different kind of power, one that works through building consensus and through loyalty to common democratic values and appeals to human rights. That raises the question of whether such an image can survive when the U.S. routinely defies broad majorities in the U.N.

Americans in the 1970s doubted it could. At the very least, the question warrants debate today.

The U.S. has to consider whether it can achieve its broader agenda while being so regularly isolated from the rest of the world on such an important issue. If not, then some adjustment to the will of the global majority would appear to be in order. Anything less, as Kissinger once warned, could carry with it more than just moral hazard. While the G-77 is no longer the force it once was, and anti-American oil embargoes appear a thing of the past, it takes but a mere glance at the day’s headlines to see that there are other potential strategic, economic, and environmental risks of isolation in 2024 that cannot be as easily dismissed.

Sean T. Byrnes is a writer, teacher, and historian who lives in middle Tennessee. He’s the author of Disunited Nations: U.S. Foreign Policy, Anti-Americanism, and the Rise of the New Right. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

Leave a comment