The evening James Baldwin stood in the pulpit of a New Orleans church in 1963, he carried little more than a single sheet of paper with his sporadic handwriting in blue ink on it. He began as he had always done: In silence, being engulfed by the applause of the room. A sort of expectation each one has arrived with.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

In a picture taken of him that evening by photographer Mario Jorrin, Baldwin’s body stood erect. He wears a dark suit. A white shirt, a black tie, and bends his chin toward the podium. The ceiling of the sanctuary seemed to climb toward the heavens as people stood crowded along the walls. There was hardly any room, a thing Baldwin had become used to since releasing The Fire Next Time earlier that year. That night, the faces of the attendees would bend toward one another—some laughed, some were stern, some were focused on the man at the pulpit, and others stared into nothing. They had all come to hear “God’s Black revolutionary mouth,” as Amiri Baraka called Baldwin.

Read More: James Baldwin Insisted We Tell the Truth About This Country. The Truth Is, We’ve Been Here Before

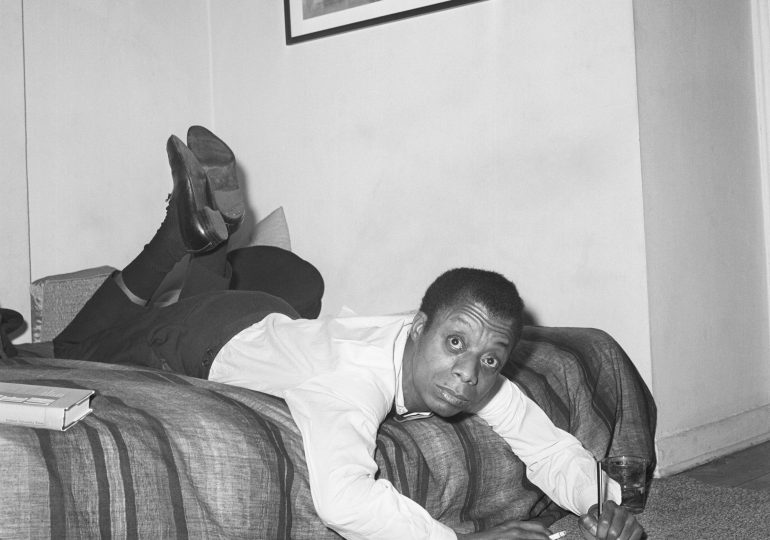

Baldwin’s frame was small, his clothes often hugged his skin. In most pictures that I have laying in my house, Baldwin smiles. I have chosen this for a reason. For years, it seemed that we have only known the angry Baldwin. That Baldwin’s thunderous appeal was only meant to break us down until we have nothing left. A foolish thing to believe any lover would do. There are four pictures, actually, four in which his cheeks spread far until they show his teeth. And yet, I know this too is a created thing. I have wanted to see him smile more than he cries. I have wanted to see him happy rather than sad. But I cannot deny this: that evening, Baldwin carried more than a paper and pen. He carried a broken heart.

A soul-crushing anguish that things at home—and in the years since leaving Harlem—would not change. An anguish that almost emptied him of keeping the faith. A painful feeling that also travels from the center of my chest this morning and the morning before that and the morning before that. “Four AM can be a devastating hour,” Baldwin writes. The clock reads 4:32am. I have just taken a sip of the gunpowder green tea, have just finished the last page of John Hersey’s 1946 essay “Hiroshima,” have read the last line—”They were looking for their mothers”—three times, underlined it with black ink that bleeds through the next page, and have become more determined, as Baldwin has, “to bear the light.”

If you are like me and are concerned with history, grief, failure, and goodness—and the way each is woven together when we tell the story of how things unfold in our lives and the lives of others—then you, too, have stared at that black and white image. You have studied James Baldwin’s hands and his eyes, remembering that the year 1963 crawls in his psyche like a never-ending plague that overworks the ventricles of the heart. You have turned to the chronology in your well-worn copy of Baldwin’s collected essays edited by Toni Morrison and see that the year 1963 was full of travel and meetings and reportings on lynching and dancing and trembling.

In the midst of all of this travel, you would realize that Baldwin had been hospitalized for what doctors call “exhaustion.” That he felt it impossible to stop because of the demands of the world. That he felt it impossible not to speak because of his broken heart. That “exhaustion” is but another word for love when you are deemed unloveable and invaluable and have refused to believe it. That you feel what Baldwin has felt and therefore have taken his essays with you everywhere because a well-worn copy of essays is somewhat an indicator of a mind that wrestles, a heart that moves, and a body that feels.

I, too, have wondered about the same world , some 60 years later, with the same type of dying in and around us. As I write these words, I am sitting at my desk at home while my daughter, Ava, is asleep upstairs. The news says the numbers of children, women, and men dead in Gaza has eclipsed almost 30,000. The streets in New York and Washington, D.C. have been filled with people crying for justice. In January, President Joe Biden stood at the pulpit at Mother Emmanuel AME, where a protester demanded a ceasefire, and the crowd responds “Four more years,” silencing the cries for dignity and protection. A few weeks before that, a rabbi stood in a crowd of people demanding the same and was met with, “Get out of here!” Neighborhoods have been flattened. Aid has been cut off. Hatred is growing. Politicians are in denial about whether or not this country was born out of anti-Black racism. I find it hard to feel anything wondering what would come of this next election year.

How do we grieve where we are now when so much has been lost? It’s in these moments that I think about Baldwin often—that I feel Baldwin’s heart and mind can be a creative force to give me the hope that I often don’t feel and the courage to allow my heartbreak to break me open instead of close me up. I think that if there is anyone to lead us through an election year—to help us ask the right questions, make the right demands, fight the good fight, and stay human—it is James Baldwin.

I think of 1963, a year that is everything but a normal year in American history. By January, the same month Baldwin wrote his intimate and thunderous appeal, 16,000 American military personnel were deployed to South Vietnam in an unjust war. By February, the fiery napalm and smoke incinerated both the bodies and fields along the Perfume River. By April, 90-year old Dorothy Bell waited for a table that never came and was eventually arrested. By May, police dogs were ripping into the rib cage of a 70-year-old black man in protest. By June, Medgar Ever’s back was split open as he bled to death in front of his wife and children. By August, burnt crosses stood illuminating the doorstops of a black family who moved into an all white neighborhood. By September, some 19 sticks of dynamite shredded the ligaments of five black girls, killing them instantly, and injuring some 20, blowing out the face of the stained glass Christ that sat behind the choir’s seating.

Read More: How Liberal White America Turned Its Back on James Baldwin in the 1960s

I have studied the image that Jorrin had taken of Baldwin that same year. The image is silent. Baldwin does not smile. His hands do not move. And yet, the image is as loud as the words he wrote in his 1963 letter to his nephew, “the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon.”

I have been thinking a lot about this image and the 60 years that has passed since this moment. The facts are this: the world is neither more safe or more healed than when he left it. The world is neither more loving or more honest or more healthy than when he was born in it. The same racism, hatred, death, and religious bigotry that Baldwin wanted us freed of in his time destroys us in our time. And yet, there is something about our time that feels different. (I am partly tired of hearing people say this moment is unprecedented because, you know, looking back through history, things have always been bad. But a part of me wonders if they are not the foolish ones, but me.) It feels different because the forces that want the world to stay the same are growing stronger. And at the same time, the inner willingness to believe that things can change, is growing deeper.

This image lingers because I too stand behind the sacred desk declaring the good news of God’s love and liberation. I too return to the blank page to feel, as Baldwin says, “what it is like to be alive.”

If there is anything that on my part and in these days that I have crawled back to, it is the way that Baldwin, as Morrison wrote in her eulogy to him, gave us language to articulate our perils, to deeply understand our place in the world not simply as humans but as people who come from a battered and worn and complex history. None of the villains and heroes in Baldwin’s mind seem quite black and white. Baldwin knew that villainy, especially of the American kind that is so double-minded and unstable in our ways about what matters and who counts, is not a given. It is chosen. And if it is chosen, then we can choose the better. This better, Morrison so beautifully articulates, is the way Baldwin so fearlessly and tenderly laid out of condition and the redemptive energy that lays at the center of it. “You went into that forbidden territory and decolonized it,” Morrison wrote. “and ungated it for black people, so that in your wake we could enter it, occupy it, restructure it in order to accommodate our complicated passions.” For Morrison, Baldwin was more than anything, full of that sacred wisdom, courage, and love that leaves us both to “witness the pain you had witnessed” and yet “tough enough to bear while it broke your heart.”

I have found myself being most concerned as of late with the things that broke Baldwin’s heart. It is not because I am obsessed with the dark side of the man who gave so much of his energy in 1963 to do what he must to make us more whole and honest and loving. It is because some 60 years later, it seems as if, on the one hand, we are so obsessed with running from grief that to deal with it is to almost give up hope because of the mountain of moral failure we feel we have to climb. And then on the other, we are living in a country where people seem to be addicted to the suffering of others.

They do not care whether your body or your brain is exhausted, they only desire your labor. They do not care whether you are you have rights or freedoms, they only care that they have them and have the power to take yours away. They do not care about your children or their children or this planet or the past or the present or the future. They only care about now and harming as many people now with as little accountability as possible.

There are days, I wonder if any of us can survive all of this. I wonder if seeing images of dead children, rage-filled desires to shred our common humanity, social media’s constant altering of our own self-image and love, the eroding of social trust and morality, the lying, the greed, the bigotry, the sleepless nights, all of it—I wonder if we can survive it.

American society for all its declarations of freedom and justice had become nothing more than empty promises and empty hopes and a “series of myths about one’s heroic ancestors, ” Baldwin wrote in October 1963, in a talk to teachers. The citizen who calls into question those, like the Good Samaritan story in the Christian Scriptures, who pass by people in need is not championed but silenced and erased. This was a cruelty, in Baldwin’s mind, of the highest order. Take the Black child and the Black adults fight for their freedom. “It is not really a Negro Revolution that is upsetting this country,” he wrote. “What is upsetting the country is a sense of its own identity.” For many in his time and even now 60 years later, the same thing is true: there is a fight to violently hold on to “American” meaning white and Christian and straight and male. For all the talk of America being a “Christian nation,” it was not just a lie, but the term “Christian nation” had become a weapon. This, too, was a deep and depressing cruelty.

Throughout his talk, Baldwin kept alluding to this idea of bad faith both as a way of being together but also bad faith as a way of living. “We understood very early that this was not a Christian nation,” he says. “It didn’t matter what you said or how often you went to church …my father and my mother and my grandfather and my grandmother knew that Christians didn’t act this way.”

When I read that line, I couldn’t help but think of what is happening right now in this country. I have thought so hard and so often about how sad it is that we live in a country where Christians have the most power, but believe they are experiencing the most pain. It’s sad that we have become so empty of not just compassion but of mercy, kindness, wisdom, and goodness. As I’ve flipped through my underlined pages of Baldwin’s text, I shook my head side to side and came to this conclusion:if anybody is making it hard to be an American and a Christian, it is Christians.

“All of these means that there are in this country tremendous reservoirs of bitterness which have never been able to find an outlet,” Baldwin posits. Sadly, that bitterness has now shown up in the most destructive and deceptive ways. And yet, that is not all Baldwin had seen. When the mind is confused, full of doubt, and discouragement, the eye must be insistent in its power to see.

After having talked about the teacher and student’s responsibility to do what we must to responsibly love one another, Baldwin turns particularly to say a word about what he would say to a black child if he were to teach them day in and day out. He would teach them that the environments that they have been forced into is not of their own doing, but that of a power that has sought to destroy them. There are no “good” kids or “bad” kids ultimately, only the conditions that mark them as such and rob the “bad” kids of their humanity and dignity.

He would teach them that their lives, their art, their history, and their story is greater than the ways this country believes them to be backward and nothing. He would teach them that the stereotypes of the world are powerful and yet not ultimate. And then the famous line: “I would try to make him know that just as American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it, so is the world larger, more daring, more beautiful and more terrible, but principally larger—and that it belongs to him.”

Read More: James Baldwin and the Trap Of Our History

I have read this line and thought of my own two children. I think of all children, truly. Children who are black as my own. Children who are Palestinian. Children who are Jewish. Children who are Asian. Children who are Hispanic, and gay and straight and athletic and quirky and in wealthy districts and left behind in enclaves. I think of them so much because, as one African proverb says, the health of the nation is dependent on the condition of its children.

I think of their growing minds and the fears that I have of what they will have to enter. How little do they know what actually awaits them and how furiously I have stayed up into the late hours of the night either praying or reading or writing in some way to prepare them. I think of my own upbringing. Our small plot of land. How little was expected of us and how much of this world we both endured and made. As a parent, I have found so much peace in those last six words: “and it belongs to him.”

Two nights ago, as I sat alone at my table reading over his talk for the third time, I took a sip of my chamomile tea as I listened to Hammock’s “We Watched You Disappear” in the background. The outside had darkened as the clouds from today’s rain passed over. I walked upstairs, noticing the chill bounce of the walls. I kiss both of my children on their foreheads as they sleep. I walk downstairs, walk back to my office, and stare at another picture from 1963 of Baldwin during his travels.

In the picture, his arms form in the position of a “T” as his body bounces side to side. The walls are bright. A painting which looks to depict an ancient time hangs on the wall. Baldwin’s eyes hang downward as the cracks of his lips widen. Doris Castle, an active organizer on the front lines of the Civil Right movement with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) stands in front of Baldwin with her torso forward, her arms like a bird’s wings, her right thumb toward the ceiling and her left index finger holding a cigarette. It was the same year that Castle protested a segregated New Orleans City Hall cafeteria. It was the same year that Baldwin went on a crusade to change the heart of the nation. In the photo, he smiles. She dances. It is said that both of them are doing the “Hitch Hike”—a dance popularized the year before with Marvin Gaye’s 1962 hit by the same name. The dance goes like this: thumb out, start to the right, four count, one, two, three, four, throw the shoulder back, left thumb out, start to the left, five, six, seven, eight, bend down, roll the hands, and turn to the left and turn to the right. And then again and then again until you are so lost together that you almost forget that a hitch hiker is a person in desperation, putting themselves in danger, hoping that they arrive where they desire as whole.

There is room made in the world, the burning and bleeding world of 1963, to dance and be joyful. There are times I wonder, as I look at this picture of both Baldwin and Castle, if their dancing kept them going. I wonder if it was their movement that let them know that their lives were more than just producing things and fighting things. To know that their existence is enough. To know that whatever good they did out there was a reflection of the good they protected in their hearts.

I have no answer to that question but something about these two images—Baldwin preaching his good news in the church and dancing his heart happy in a home—remind me that Baldwin left more than a broken heart. He left us a beating heart. “My ancestors counseled me to keep the faith: and I promised, I vowed, that I would,” he wrote. I, too, have made that vow. I, too, have watched my own children dance, twirl their bodies around the dying grass, laughing and holding hands. I, too, have watched people take the streets once again to say to the world: if they can’t be free, then we can’t be free. I, too, have watched the artist and poets among us move their tender fingers toward the keyboard and the page, determined to create against all hope. I, too, have watched how we have done something as simple as cried at the sight of one human being helping another, trusting that every good deed can be multiplied. A broken heart isn’t the only type of heart.

There is also a heart that with every act of courage, tenderness, vulnerability, kindness, and mercy, moves forward.

Leave a comment