Amid growing maternal mortality rates, Black and Indigenous women in the U.S. are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women. Many women of color experience painful and traumatic hospital experiences as a result of structural racism and being historically neglected by the American health care system. And while maternal care experts have noted the improved health outcomes that come with midwifery care—less medical intervention and fewer C-sections—over 90% of midwives are white, highlighting how hard it is for Black women to find Black providers.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But it always wasn’t this way. In 19th century America, interracial midwifery was the primary form of prenatal care. And yet, as childbirth became more medicalized, Black women and women of color were erased from providing maternal health care. Understanding the origin of this disparity is key to addressing the shortage of midwives of color and making the profession more diverse.

For generations, pregnancy care and childbirth were overseen by trainee midwives throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, and later, North America. Midwives would not only support the mother through the emotional pain of labor, but also administer medicine, ensure general hygiene, and take care of the mother and her baby following the birthing process.

In the U.S. before the Civil War, Black, Indigenous, and immigrant women imparted traditional healing practices and wisdom by engaging in apprenticeships alongside more experienced midwives within their communities. According to census data, midwifery was interracial: half of the women who provided reproductive health care were Black, and the other half were white and Indigenous.

Read More: Elaine Welteroth: Using Midwifery Care Was the Best Decision I Ever Made

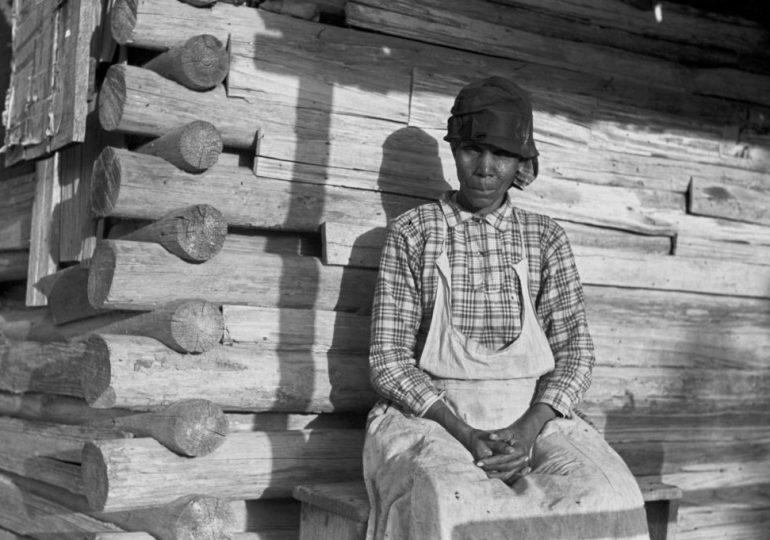

Despite the harsh restrictions of slavery, African American midwives were granted a high degree of mobility—they could travel and accept payment for their labor, which was rare among enslaved individuals. They were the primary providers of prenatal and birth care across the country, including, often, for their enslavers’ wives. Midwives were pillars of their community, maintaining social networks and keeping records even when families were separated and members were sold to new owners.

Midwives used both spiritual and medicinal remedies to treat a variety of ailments and ensure infants were in good health, but the services they provided went beyond childbirth. For some women, midwives were often the only available healthcare providers. One of their key roles was administering birth control and abortifacients. During slavery and for many years thereafter, African-American women lacked autonomy over their bodies as they endured heavy physical and sexual abuse. Choosing to have an abortion empowered them, providing a way to assert and preserve control over their bodies.

The majority of midwives in remote and rural parts of the South were Black. Dubbed “Granny Midwives,” they served as a strong force in alleviating reproductive health disparities and bridging gaps in maternal care. While formally trained physicians and medical practitioners existed, they often practiced in more urban areas and neglected patients of color.

Even after abolition, Black women preferred delivering at home with the help of a midwife rather than at a hospital due to the prejudice and discrimination they experienced in society.

However, the midwife role changed in the 20th century as the practice of child delivery became a medical specialty dominated by elite white men who asserted the importance of professional pedigrees, modern technologies, and the convenience of hospitals. As maternal mortality rates declined—due to increased sanitation and newly developed hygiene practices—white male obstetricians started to question the practice of all midwifery. The medical community also targeted Black midwives and midwives of color as posing another threat to their work, and excluded them from practicing within their establishments. In “The Development of Midwifery in Mississippi,” Dr. Felix J. Underwood, director of the Bureau of Child Hygiene for Mississippi, wrote: “What could be a more pitiable picture than that of a prospective mother housed in an unsanitary home and attended in this most critical period by an accoucheur, filthy and ignorant, and not far removed from the jungles of Africa, laden with its atmosphere of weird superstition and voodooism.”

As a result of this gender and racial prejudice, negative stories and anti-midwife sentiments began to circulate in the media and in medical journals. An article in The Birmingham-Age Herald newspaper stated, “the midwife should be eliminated and her work should be taken over by physicians and nurses.” White physicians even blamed midwives for being responsible for maternal deaths during childbirth—until the 1930 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection published research showing that the percentage of midwife-attended births did not influence high maternal mortality in any particular area of the country.

Many wealthy, white families started having babies under the care of white physicians because they viewed midwives as dangerous, unhygienic, and of lower status.

Midwifery still thrived in Black communities, especially in the South. For a Black woman, a midwife remained a more affordable, safer, and comfortable option—particularly at a time when she enjoyed fewer rights and little respect.

Nonetheless, the assault on the practice of midwifery by white physicians drove down the number of midwives. Even worse, this drop-off worsened birth and pregnancy outcomes—especially for Black mothers and birthing people, who struggled to find Black health care providers who made them feel secure and cared for. Julius Levy, a physician and researcher at the Bureau of Child Hygiene in the New Jersey State Department of Health, found that, among U.S. cities, “the lowest maternal mortality rate is in the city with the highest percentage of births delivered by midwives.” In Newark, N.J., the percentage of practicing midwives decreased from 48% in 1917 to 38% in 1921, while in the same five year period the maternal mortality rose from 4.1% to 6.5%.

In 1921, Congress passed the first federally funded social welfare program, the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act, in an effort to reduce alarming rates of maternal and infant mortality. It encouraged states to adopt their own maternal care legislation, and many of them began requiring midwives to be certified. As nurse-midwifery formalized, white practitioners began to dominate the profession as they began training programs that excluded Black women.

Even the Tuskegee School of Nurse-Midwifery, opened in 1941 specifically to increase representation of Black nurse-midwives, created additional barriers among this population. The stringent requirements and high tuition excluded many older, poor, rural Black women who had been practicing as midwives for most of their lives. As a result, fewer Black women enrolled and the school closed five years later in 1946 due to a lack of funding.

Read More: The History Behind America’s Devastating Shortage of Black Doctors

Without access to affordable training programs, Black midwives faced state legal and regulatory rules to prevent them from practicing. Many midwives who had built a profession for themselves were now out of work as they were labeled as filthy and illicit by white leaders. Those who stayed and got trained as nurse-midwives soon started working collaboratively with obstetricians as a part of a patient’s overall health care team, at medical institutions they were once banned from entering.

In the mid 20th century, as Black physicians started to establish their careers and gain legitimacy, many of them joined their white colleagues in discriminating against midwives. They felt that by criticizing the work of midwives—even Black midwives within their own communities—they would be accepted and respected by their white colleagues.

The half-century campaign against midwives took its toll: by 1950, midwives only attended 5% of all births in the U.S., though they continued to be present for 25% of all non-white births.

Due to the nation’s dark history, it’s been a long journey for midwives—especially those of color—to be able to practice in their communities.

Even today, the number of Black midwives is disproportionately low while the Black maternal mortality rate is disproportionately high. The two are connected, as the historical erasure of women of color in the reproductive health care space has further exacerbated maternal health disparities. This lesson can guide policymakers into increasing representation of Black midwives and midwives of color to shift the balance of power and support new moms.

Anika Nayak is a writer and Journalism and Women Symposium Health Journalism Fellow, supported by The Commonwealth Fund.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Leave a comment