Spoiler alert: This piece discusses the Curb Your Enthusiasm series finale.

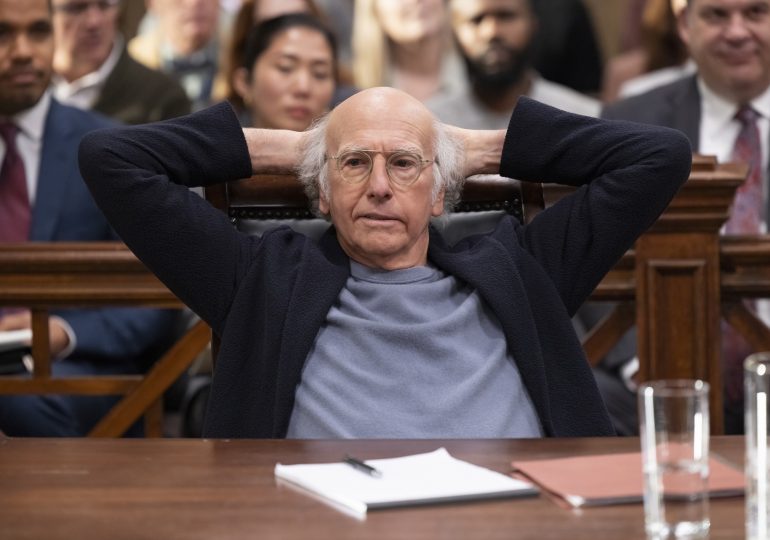

“I am 76 years old, and I have never learned a lesson in my entire life,” Larry David informs a little boy in a hotel lobby, early in Sunday’s Curb Your Enthusiasm series finale. Then, for those who weren’t already convinced by 12 seasons and 24 years’ worth of Larry the TV character’s antisocial antics, David the creator goes on to prove it by wrapping up his HBO comedy in much the same, wildly unpopular way he ended Seinfeld. Once again, a trial unites some of the series’ most memorable minor characters in an indictment of the protagonist’s selfish, petty behavior. In place of Soup Nazi and the low talker, we got Mocha Joe, Rachel Heineman of ski lift fame, and the girl Larry traumatized by giving her a hug with a bottle of water shoved down his pants—now a grown woman who’s still working through the incident in therapy. And once again, the verdict is guilty.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

David’s motto for Seinfeld, which flew in the face of 1980s and ’90s broadcast-comedy norms shaped by saccharine family sitcoms, was “no hugging, no learning.” The title of the Curb finale, “No Lessons Learned,” reiterates that TV Larry and real-life David have been, for the past 35 years, the same schlemiel we first met in the form of David’s hapless Seinfeld avatar, George Costanza. Yet, if you look closely at the end of Curb, you’ll find that something notable has shifted since a Massachusetts jury sentenced the so-called New York Four to a year behind bars. While Larry remained in arrested development, the world around him took a dramatic turn for the worse.

Consider the court cases that end each series. Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer are dragged before a judge for failing to intervene in a carjacking. Instead of helping a man whose vehicle is being stolen, at no apparent risk to themselves, they violate a newly enacted Good Samaritan Law by cracking jokes about the victim’s weight while videotaping the crime for their own future amusement. When they’re condemned to a year in prison, it’s because they violated society’s moral standards. The New York Four, who mock and manipulate and obsess over minutiae while shrugging off the wellbeing of others and the world at large, are essentially convicted of being bad people. Seinfeld fans who hated this conclusion felt implicated in David’s condemnation of his characters.

The Larry we’ve gotten to know in Curb is no better than those characters. But the transgression that lands him in an Atlanta courtroom is in no way symbolic of his moral bankruptcy. The law he breaks, Georgia’s Election Integrity Act, which prohibits the distribution of food or water on voting lines, is one that no fair-minded person—and certainly not David, a liberal who has made headlines for telling off Alan Dershowitz and excoriating Donald Trump—could support. Larry isn’t trying to make a statement, in the Season 12 premiere, when he delivers a drink to an overheating Auntie Rae (Ellia English); he’s still running damage control after behaving rudely towards her earlier in the episode. Yet his high-profile arrest embroils him in a partisan political war that he experiences as a shortcut to Hollywood heroism and, briefly, the arms of Sienna Miller (appearing as herself).

He’s hardly the only character capitalizing on liberal goodwill. Even Ted Danson, who has long played a fictionalized version of himself on Curb, is the subject of David’s parody when the actor and sometime activist leads a self-serving pro-Larry protest outside the courthouse. Then there’s the other side of the aisle. During the trial, David once again pokes fun at Trump. Larry’s bribery of a city councilwoman, Tracey Ullman’s gloriously crude Irma Kostroski, gives the show an excuse to put real White House whistleblower Alex Vindman on the stand to testify to our hero’s corruption. “It was a perfect call!” Larry shouts, in an echo of the former President’s statement on a phone conversation in which he attempted to influence Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate Joe Biden.

It’s no surprise when Larry is sent to prison, after receiving the same one-year sentence as the Seinfeld crew. Yet Curb ends on what appears to be a lighter note: Guest star Jerry Seinfeld spots a juror, who happens to resemble Joe Pesci in Goodfellas, breaking sequestration. A mistrial is declared. And Larry walks free, musing to Jerry that this is how Seinfeld should’ve ended. Has the ordeal taught him anything about what really matters in life? Of course not. In the final scene of the series, Larry is on a plane back to L.A. with his closest friends, blithely bickering over whether his nemesis (frienesis?), Susie Essman’s Susie Greene, has the right to open the window shade.

This is an absurd resolution to a predicament that has been absurd since the very beginning. But there’s a certain logic to it, in an era of heightened rhetoric and casual injustice, when so little of the news cycle makes factual, much less moral, sense. While the Seinfeld characters were anathema to the mores of a relatively healthy mainstream society, Larry and his ultimate fate are products of one that is sick.

David would probably brush off this reading. “I just try to write funny shows,” he told MSNBC’s Ari Melber at a pre-finale event this past Friday, repeating a claim he’s made many times before. “That’s all it is. I’ve never analyzed it.” Fair enough. But it doesn’t mean that, from the show about nothing to a Curb finale that relitigated that show, he hasn’t given the rest of us plenty to chew on.

Leave a comment