At least since the 1800s, colleges and universities in the United States have emphasized their civic missions. American college students weren’t just supposed to get better at exams and recitations, they were supposed to develop character traits that would make them better citizens. In the last fifty years, whether one attended a large public university or a small private college, chances are the mission statement of your school included language that emphasized the institution’s contribution to the public good. So why today is there a chorus of critics urging higher education leaders to cultivate neutrality, to cede the public sphere to others?

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

I suppose that in these days of social polarization and hyper-partisanship, some see campus life as a retreat from the bruising realities of political life. You can pursue theater or biology, religion or economics, without worrying too much what the person sitting next to you thinks of the political issue of the day. And if your institution has no political commitments, so the thinking seems to go, you may feel more inclined to form your own, or just not to have any at all. Whether one weds this to a monastic view of higher education, or skills-based vocational one, one can feel that university life provides a respite from the take-a-stand demands of the political. While there is certainly freedom in that, it should be remembered that we only have that freedom because of guarantees established by generations of political struggle.

One of those fundamental guarantees is the ability to choose one’s field of study, to conduct research without political intervention, and to openly discuss the results of one’s work. In his forthcoming book Academic Freedom: From Professional Norm to First Amendment Right, David Rabban argues convincingly that academic freedom is a distinctive first amendment right, one which protects teachers and researchers while enabling society as a whole to benefit from the production and dissemination of knowledge. The American Association of University Professors sketched out this foundational professional norm in 1915. Scholars are free to explore issues and to debate them; they should be able to take positions that might turn out to be very unpopular in the broader political realm. Rabban shows how these protections have been protected in a series of court decisions over the last hundred years. Whether teaching the Bible, a contemporary video, or evolutionary biology, professors should not have to worry that political pressures will force them away from a path of inquiry or a mode of expression.

Today, though, such worries abound. Libraries are banning books at alarming rates, faculty are being disciplined for their political views, and student rights to protest are being curtailed beyond appropriate “time and place” guidelines. Issues around the right to speak one’s mind are front and center on college campuses, thrust there in part because of protests around the war in Gaza and the spectacle of congressional hearings about antisemitism. Ivy League institutions have attracted the most attention for outbursts of Jew hatred even as scores of civilian hostages from Israel are subject to torture, rape, and brutal isolation. But rejecting the vicious tactics of the war in Gaza, doesn’t make one a supporter of terrorist violence; starving Palestinians in Gaza won’t secure freedom for the hostages. In these dire conditions, it’s no wonder that colleges are faced with legitimate protests as well as traditional expressions of prejudice and hate. On campuses across the country, Islamophobia and antisemitic harassment can destroy the conditions for learning, but mass arrests of peaceful protestors and the censorship of speakers for their political views only undermine academic freedom in the long run.

In recent years, some progressives have expressed doubts about free speech, describing it as a neo-liberal disguise of existing power relations. Now, however, as those aligned with pro-Palestinian movements are being censured or arrested, the old liberal approach to freedom of expression seems more attractive to many protestors. Historians Ahmna Khalid and Jeffrey Snyder have been writing about these issues, and recently they gave a powerful presentation to a packed house at Wesleyan. They began with a critical appraisal of Florida’s various attacks on academic freedom, which on my campus was preaching to the choir. But the speakers went on to discuss how many of efforts that fall under the popular rubric of inclusion are also aimed at suppressing speech ostensibly to protect so-called vulnerable communities. Protecting students against speech in the name of harm reduction is almost always a mistake, they argued. Here, the debate got interesting. And this was their point: debates are only interesting when people are free to disagree, listen to opposing views, change their minds. But they also seemed to agree that in some cases intimidation could be intense enough to warrant restrictions on expression. I call this a “safe enough space” approach to speech, but in the discussion following their talk it was clear that they thought my pragmatist position left too much room for unwarranted “safetyism.” There was a real conversation; students and faculty were fully engaged.

Read More: The New Antisemitism

And that, of course, is when learning happens: when we are engaged in deep listening and in trying to think for ourselves in the company of others. This is what I argue in The Student: A Short History: being a student—at whatever age—means being open to others in ways that allow one to expand one’s thinking, to enhance one’s capacities for appreciation, for empathy and for civic participation. That participation energizes a virtuous circle because it’s by engaging with others that one multiplies possibilities for learning (and then for further engagement).

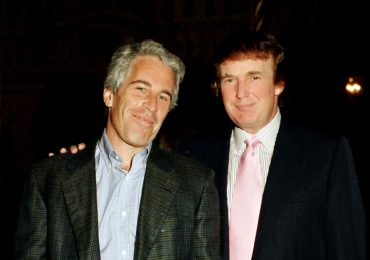

That virtuous circle depends on freedoms in a political context under direct threat from the populist authoritarianism movement led by Donald Trump. When Trump attacks his enemies, when he talks about them as thugs and vermin or proposes his own national university to replace the elites so despised by his base, he is telegraphing his intentions to remake higher education in the image of his MAGA movement. Many academics seem to shrug their shoulders, saying either that “other politicians aren’t so great either,” or to suggest (as elites often have when faced with growing fascist threats) that he doesn’t really mean what he says. This is a grave mistake, as we’ve seen before in history.

Neutrality, whether based on principle, apathy or cynicism, today feeds collaboration. The attack on democracy, the attack on the rule of law, will also sweep away the freedoms that higher education has won over the last 100 years.

We can fight back. Between now and November 5th, many of our students, faculty, staff and alumni will be practicing freedom by participating in the electoral process. They will work on behalf of candidates and in regard to issues bearing on the future of academic freedom, free speech, and the possibilities for full engagement with others. This is challenging work. In the noise of contemporary politics, it’s hard to practice authentic listening; in the glare of the media’s campaign cameras, it’s hard to see things from someone else’s point of view.

But that is our task. If we are to strengthen our democracy and the educational institutions that depend on it, we must learn to practice freedom, better. We must learn to be better students. Our future depends on it.

Leave a comment