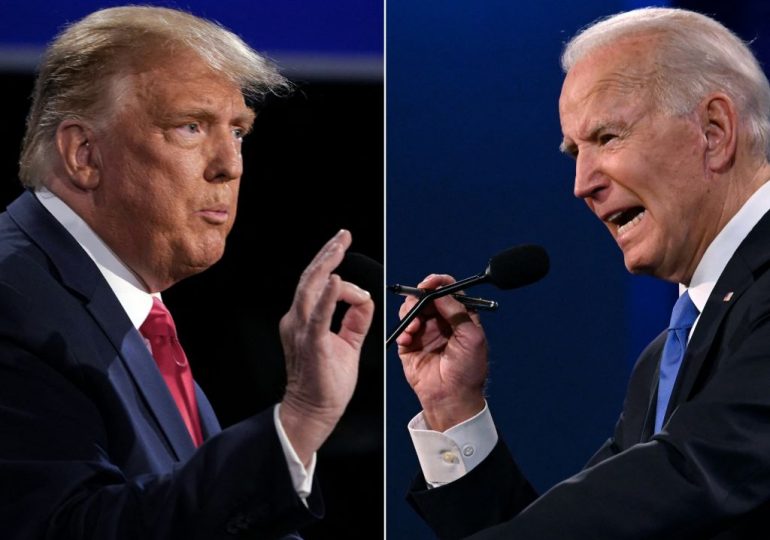

Tonight, President Joe Biden and former president Donald Trump face one another in an unprecedented televised debate. The format has been around since the 1960 presidential election, but the timing, structure, and candidates themselves—notably one being a convicted felon—represent uncharted waters for TV debates.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Typically, the media zeroes in on protocols, performance, polling, and gaffes—with journalists often prioritizing horse-race style coverage over voter education. How might the debate nudge the scale for the candidates, as determined by the inevitable follow-up polling? Will a candidate perform up to expectations? (If expectations are low because a candidate is known as a poor debater, a B+ performance will be understood as an A+ victory.) Will candidates discuss issues with one another, or will rules such as time limits merely enable pre-scripted talking points? And will there be any big gaffes that one side can weaponize against the other? Likewise, if a candidate scores a rhetorical coup, how will a zinger be good fodder for campaign teams to hype?

These trivialities trouble those who understand debates as venues that should provide solid information to undecided voters. And yet, if today’s debates are media showcases that have evolved into gotcha contests—where victory comes down to which campaign can best weaponize an opponent’s sound-bite-size gaffe into a meme for social-media circulation—that doesn’t mean that they used to do a substantially better job at furthering the democratic project. Taking a glass-half-empty perspective, one might conclude that televised debates have never actually served the noble democratic purpose that their idealist supporters imagine.

Read More: Your Questions About Presidential Debates, Answered

In fact, their origins were more pragmatic than high-minded. Debates were not broadcast in the 1950s, in part out of legal concerns. Federal regulations required equal airtime for all candidates, not just those of the two major parties. The networks didn’t want the headache.

That changed in 1960 out of practical necessity and in an effort to atone for scandals—liked rigged quiz shows. Facing both a public-relations crisis and pressure from the FCC and Congress to do better, broadcasters suddenly expressed a renewed commitment to public service. Congress suspended the equal time clause, and televised debates were born.

From the very beginning, the moments from televised presidential debates that generated news coverage in the days and weeks after the event had little to do with policy substance.

That first year, Nixon made a poor visual impression. Journalist Theodore H. White reported that the Lazy Shave face powder he wore to hide his five-o-clock shadow was “faintly streaked with sweat” and that at points he was “haggard-looking to the point of sickness…his eyes exaggerated hollows of blackness, his jaw, jowls, and face drooping with strain.” These visuals stuck in the public mind long after the telegenic John Kennedy won the election.

After a hiatus of three election cycles because the frontrunners had little incentive to face off against their challengers, debates returned in 1976 in the showdown between Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. In their first debate, the audio went out on the broadcast, forcing a delay of 27 minutes while technicians fixed the problem. Carter and Ford remained frozen at their podiums the entire time. Carter later recalled, “it was embarrassing to me that both President Ford and I stood there almost like robots.” Each thought he might look weak if he sat down, but instead, both seemed a bit foolish.

Then in their second face-off, Ford made the first famous gaffe in televised presidential debate history. He seemed to imply that he did not understand that Eastern Europe was under Soviet domination. Ford thereby reinforced popular images of himself as bumbling and an “accidental” president.

In 1980 and 1984, Ronald Reagan, a former actor, showed that the inverse was true: policy substance and vision mattered less than a good wisecrack. He put to bed questions about his age and fitness in 1984 by remarking, “I will not make age an issue in this campaign. I will not exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” Everyone laughed, including opponent Walter Mondale, and the quip had suddenly apparently solved an issue that was actually much more serious than a one-liner.

Read More: Presidential Debates in History That Moved the Needle

In 1988, Michael Dukakis learned that trying to be substantive and serious could actually damage a candidate. Asked at the second debate if he would support the death penalty against an offender who raped and murdered his wife, Dukakis offered up a policy explanation for his opposition to the death penalty, leaving viewers with the impression that he was cold and uncaring.

Despite these regular reminders that appearances, easily caricatured sound bites, and good one-liners mattered more than substance, idealists continually fought to find ways to make the debates matter to civic discourse, none more so than Newton Minow. The former FCC chair was one of the key players who worked to establish the Committee on Presidential Debates (CPD) in 1987 to take control of the quadrennial showdowns from the League of Women Voters.

Minow lamented that “despite its valiant efforts the League simply did not have the clout to succeed.” The debates were assembled ad-hoc, and the campaigns engaged in petty negotiations that the League found challenging to referee.

The CPD seemed to bring more stability, in part by diving into the groundwork far in advance of the actual events. In late 2023, for example, the commission selected Virginia State University as a site for a presidential debate to be held this October, which would make it the first historically Black college or university chosen to serve this role. It was a crushing blow, then, when the CPD was later pushed out of the process, as Biden and Trump chose to debate much earlier, first in Atlanta hosted by CNN this week, and later in September at a to-be-determined location, hosted by ABC. This points to the continued precariousness of these political rituals that we have come to expect every four years.

With the CPD elbowed out, perhaps permanently, this year marks a turning point. For one thing, there will now be ads, an entirely new, and some argue, corrupting presence, as if the debates had not been profitable for broadcasters in the past.

Incredibly, given the rise of social media and the fragmenting of what was formerly the mass American viewing audience, the debates actually do attract strong viewership numbers. In 1980, the Carter-Reagan debates pulled around 80 million viewers. Almost the same number tuned in for the first debate in 2020, even as TV news watching in general had plummeted. The U.S. population increased by some 100 million people in the intervening 40 years, so those numbers are not equivalent, but still, such high ratings show that TV debates, along with nominating conventions, remain the Super Bowl of elections. Broadcast and cable news outlets have good reason to hang onto them, regardless of whether or not they help voters make their choices.

Read More: The First Televised Presidential Debate Isn’t What You Think It Was

And so, even as the CPD has fallen out of the picture, there are still protocols in place, most notably an agreement that the mics have a cutoff switch and that the event takes place without a studio audience. That means Trump will not be able to work a crowd into a frenzy, and he won’t be able to talk over Biden incessantly, as he did at the first debate in 2020.

Such ground rules will help Biden make his case, but these two men are unlikely to offer brand new visions for the future or reveal previously hidden character traits. As we’ve seen in the past, the perceived champion in this horse race will probably be the one offering the best one-liners while avoiding gaffes that can be distorted (or even deep-faked) and go viral. Biden will likely emphasize his achievements, the value of democracy, and the importance of fighting for women’s health rights and rule of law, while Trump will likely hammer home messages about inflation and the border, while also engaging in misdirection, speaking in half-truths, and getting personal by attacking Biden’s recently convicted son.

With such off-the-rails discourse flying, it might be amusing to wonder which horse will win the debates this season, if the stakes weren’t so high.

Heather Hendershot is the Cardiss Collins Professor of Communication Studies and Journalism at Northwestern University. Her most recent book is When the News Broke: Chicago 1968 and the Polarizing of America.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Leave a comment