Professional wrestling has always had a unique relationship with the truth. The most obvious example of this mercurial bond is kayfabe, performers’ efforts to present everything that happens in the ring as 100% true and spectators’ agreement to accept this, but in reality the phenomenon goes far beyond the squared circle.

As author David Shoemaker puts it in the second episode of Netflix’s new documentary series Mr. McMahon, “Nothing that anybody involved in wrestling tells you should be regarded as fact.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

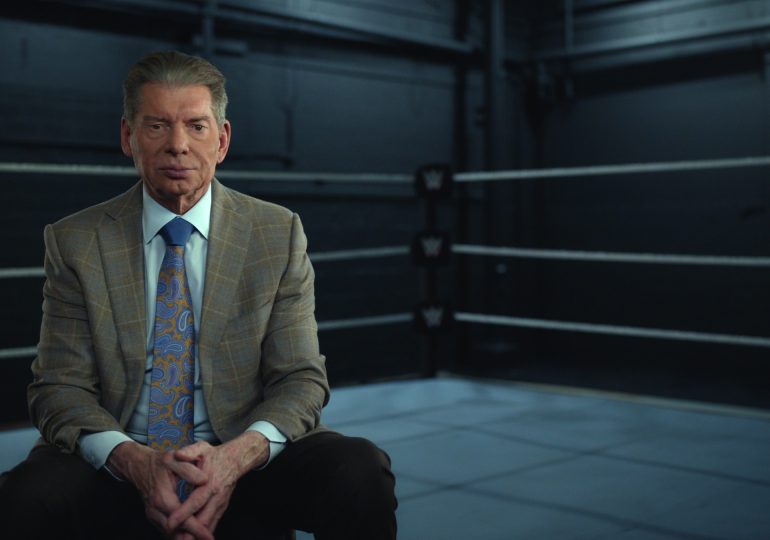

Since pro wrestling’s early days as a carnival sideshow attraction, performers and behind-the-scenes staff have misled the media, fans, and even themselves for purposes ranging from harmless to sinister. Some become unsure of where their characters end and real life begins. Promoters exaggerate their attributes and obfuscate their problems to make more money, solidify their legacies, and avoid fallout for any misdeeds. WWE founder and figurehead Vince McMahon was particularly adept at this. He even managed to rebound from his first retirement as WWE CEO and chairman amidst allegations of sexual misconduct in 2022 before a lawsuit filed by former employee Janel Grant, alleging that McMahon had subjected her to sexual assault, trafficking, physical abuse, and “extreme cruelty and degradation” led to his resignation, again, in late Januaury, 2024.

It’s not easy to honestly and thoroughly cover any aspect of this business when you have to constantly navigate all of the above. It’s even harder when your subject matter involves a company as dedicated to controlling its image and massaging its history as the WWE has been over the course of its 45-year existence (or 70-plus years, if you count its pre-WWF-branded origins). Some sports writers, including people featured in Mr. McMahon, have made valiant and valuable efforts to deliver serious reporting on the topic. The Vice TV series The Dark Side of the Ring has made some decent headway outside of the WWE’s reach over five seasons released since 2019. The show’s talking heads, a mix of wrestlers, promoters, and experts, can’t resist a certain degree of self-mythologizing, but it has produced probing looks at serious incidents involving the WWE, including Chris Benoit’s horrifying family annihilation and the infamous “Plane Ride From Hell.”

Productions that have been granted any degree of access to the company haven’t been able to get very far. Even acclaimed films like Beyond The Mat, and Hitman Hart: Wrestling With Shadows, both released in the late 1990s, offer only fleeting glimpses behind the company’s curtain. Most of the current “factual” content involving the WWE is produced by the WWE itself, which has yielded a lot of rose-tinted profiles of stars and pivotal moments.

When the WWE announced in 2020 that they’d sold a multi-part documentary series on embattled WWE co-founder and figurehead Vince McMahon with The Ringer’s Bill Simmons as executive producer and Fyre and Tiger King’s Chris Smith directing and producing, there was little reason to believe they’d have better luck penetrating the palace walls. Simmons and Smith are a respected journalist and filmmaker, respectively, with proven track records. But nothing in the early days of this particular project suggested that they were any match for the WWE machine. It didn’t help that Simmons’ previous collaboration with WWE studios, HBO’s 2018 documentary film André the Giant, while well made, wasn’t especially hard-hitting. The fact that WWE President and Chief Revenue Officer Nick Khan gushed about an early cut of the series, calling it “out of this world, amazing” in a Q3 2021 Earnings Call, wasn’t promising, either. Few experts in the field or fans with any knowledge of how the WWE operates—myself included—expected Simmons and Smith could take on WWE’s insular universe.

Judging by Mr. McMahon’s interviews with its key subject and his most vehement yes-men, like Terry “Hulk Hogan” Bollea and WWE Executive Director Bruce Pritchard—the majority of which were filmed before the most recent sexual misconduct allegations against McMahon—no one in his inner circle thought they could, either. Which might be the series’ greatest asset. Years of softball questions for whitewashed productions appear to have left McMahon ill prepared for the most rudimentary journalism. He blithely brags and confabulates, fudges easily refutable details like attendance numbers, makes spurious arguments (he doesn’t believe that Mark Calaway, a.k.a. the Undertaker, suffered a concussion during his Wrestlemania 30 match against Brock Lesnar and suggests that the star’s extensive physical symptoms were actually a trauma response to having to lose), and smugly declares that he’s working the crew as he speaks to them as if everyone involved will be sympathetic to him and no one will consider any fact checking or follow-ups. All that Simmons and Smith have to do to make this footage more than a hollow and bloviated tribute to McMahon is the fundamentals of their jobs. And they do.

It’s impossible to guess what the tone of the show might have been before the sexual abuse allegations against McMahon, which are referenced in multiple episodes and unflinchingly discussed in the finale, halted production and shifted the focus in 2022. But the version that does exist is far from the puff pieces fans of the league have come to know. (In another departure from the formula, WWE Studios is no longer associated with production.) Throughout the six-episode series, the Mr. McMahon crew give their titular subject the opportunity to tell his side of his story, starting with his impoverished childhood and weaving through four decades of highs and lows in the WWF-turned-WWE’s history. Then they repeatedly follow up with a mix of interviews with industry leaders and experts, archival news, and footage from McMahon’s own programming, to provide greater context for—and often flat out debunk—what he’s saying.

The breadth of the show’s coverage is fairly substantial. It touches upon a number of serious issues that McMahon and his company prefer to gloss over or sidestep, including labor abuses and union busting, the steroid trial, the ring boy scandal, referee Rita Chatterton’s rape allegations against McMahon, the suspicious death of Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s girlfriend, Benoit’s double murder-suicide, Ashley Massaro’s rape during a WWE appearance at a military base and the company’s efforts to cover it up, and the current civil lawsuit around sexual trafficking against McMahon and the federal criminal investigation it has spawned.

The cast of interviewees that the series has assembled is mostly up to the task of discussing these topics and many more, too. Former wrestlers Anthony White, a.k.a. Tony Atlas, and Bret Hart give clear-eyed (by wrestling standards) looks into the era in which they worked for the WWF. The Wrestling Observer’s Dave Meltzer does an excellent job of breaking down the WWE’s history in a way that is comprehensive enough for people who follow wrestling but still accessible for the uninitiated. Authors Sharon Mazer and David Shoemaker provide vital cultural criticism. Veteran New York Post columnist Phil Mushnick frankly discusses his decades-long coverage of McMahon’s professional and personal misdeeds while reporters Khadeeja Safdar, Ted Mann, and Joe Palazzolo provide insights into their recent investigations into his crimes.

Mr. McMahon is not perfect. While I appreciate that time constraints would make it almost impossible to properly investigate every scandal related to the WWE over the course of six episodes, some of them get little more than a fleeting mention here. (Netflix described the series in marketing materials as being culled from more than 200 hours of interviews with McMahon alone.) It’s significant that Snuka was acknowledged at all, but it’s a shame that there wasn’t the time, resources, or interest to investigate the long-standing rumors that the then WWF might have played a role in covering up his involvement in Nancy Argentino’s death.

Some periods of the WWE’s history are more thoroughly explored than others. The post-Attitude Era coverage in particular would have benefited from more cultural criticism and expert opinions. It’s odd that the series seems content to allow modern-day stars like Cody Rhodes insist that the current version of the company is supportive and devoid of the issues that plagued the rest of its history without the pushback that almost every other claim receives. (Although it’s convenient for Netflix, which will begin streaming WWE Raw in 2025, that their show is apparently completely separate from anything unsavory covered in this series.)

Despite its minor flaws and the limitations of its scope, though, the series remains a solid interrogation of McMahon’s life and work. I’ve followed wrestling for too long and seen too many improbable McMahon comebacks to be able to declare with any confidence that he won’t bounce back once more, but I believe that it will leave a permanent mark on his ability to control his own narrative. All of the usual tricks he’s employed to aggrandize himself and avoid accountability throughout his career are laid bare here. He mythologizes and exaggerates the details of Wrestlemania III and the producers immediately follow up with actual attendance numbers and background information about its stars. He shrugs off proven instances of harm as isolated events while the series has already made a solid case that they were consistent with his patterns of behavior and the company culture he fostered. And he keeps trying to draw a definitive line between himself and his alter ego and pin every accusation and criticism he’s received on the latter. (In fact, he’s still doing it. In a statement shared on X on Sept. 23, McMahon accused the producers of conflating himself with his character.) But the entire show serves as convincing evidence that no clear boundary between person and persona exists.

Mr. Vince McMahon might have believed that he could talk and confabulate his way out of anything the people involved in this production threw at him when he agreed to participate. But by the end, it’s clear that the only person he’s successfully worked is himself.

Leave a comment