The working class’s continued attraction to Donald Trump has long rankled his opponents, who argue that his biggest first-term policy accomplishment, the 2017 Tax and Jobs Act, disproportionately benefited the wealthy. They see the President-elect as exploiting fears about cultural change and immigration to sell working people a bill of goods.

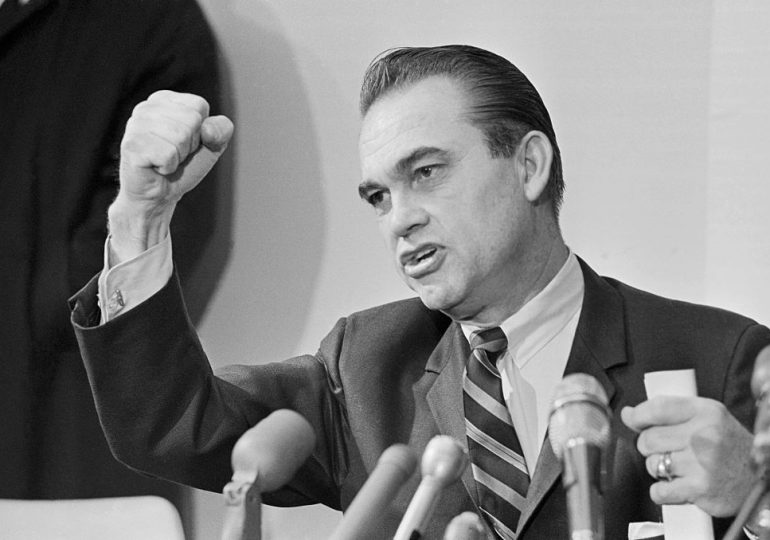

The history of another conservative populist — former Alabama governor George Wallace — indicates that such fears are well founded. Wallace is most remembered for the racism and racial violence he unleashed on civil rights protestors in the state during his first term as governor (1963-1967). Yet, looking at his subsequent, oft-forgotten time as governor in the 1970s and 1980s sheds light on Trump’s populist appeal, while also underscoring the likelihood that his business-friendly policies will actually hurt his base of working-class voters.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Wallace continuously wielded populist rhetoric and maintained support from working-class white Alabamans. Yet, after the successes of the civil rights movement in the 1960s threatened to dilute his power base, the governor joined forces with special interest groups to promote policies intended to protect big business at the expense of everyday Alabamans. The result was sky-high sales taxes, poor public services, and limited economic mobility.

Wallace entered office in 1963 as the state was already beginning to change economically. Alabama’s billion-dollar timber industry had just surpassed heavy metals as the economic leader in the state. Timber and paper companies were eager to buy up as much land from farmers as they possibly could to take advantage of Alabama’s cheap land and low taxes.

Read More: Trump — The Incoherent Demagogue

Big businesses like these especially targeted land in rural, majority-Black counties, where disenfranchisement allowed whites to control the county positions that determined the property-tax assessment rate. These white officials kept taxes low, which disproportionately helped the businesses that were buying up huge tracts of land. The companies feared that if Black officials were elected, they would raise property taxes to pay for much-needed social services, thereby severely damaging their bottom line.

That made the staunchly segregationist Wallace an ally, although their alliance was far from obvious in the governor’s rhetoric. Wallace mixed his racist appeals to white Alabamans with ample populist rhetoric, which portrayed him as a defender of Alabamans’ right to have a say in their own government. His calls for “freedom of choice,” state’s rights, and low taxes appealed to working-class white Alabamans who saw the social, political, and economic changes of the 1960s as a threat to their “way of life.”

Yet, if one dug beneath Wallace’s rhetoric, it became clear he was wielding white supremacy to defend a tax structure that allowed white elites to take advantage of the very people Wallace claimed to protect.

Wallace railed against the 1965 Voting Rights Act and federal mandates to reapportion the legislature as attacks on local control. Federal orders to equalize representation and taxation, he argued, were really ploys to force whites to pay more taxes for “radical” civil rights initiatives.

The real threat of those federal mandates, however, was to the corporate bottom line for Wallace’s biggest benefactors. Meanwhile, it was the policies that Wallace was pushing which actually hurt the white Alabamans the governor claimed to be protecting. To keep property taxes low for big business, for example, the governor had to raise sales and excise taxes just to pay for essential government functions.

Wallace left office in 1967 and waged an unsuccessful battle to win the presidency in 1968. Then in 1970, he ran to recapture the governorship from Albert Brewer, who had succeeded Wallace’s wife Lurleen as governor when she died of cancer in 1968.

Wallace ran a rabidly racist campaign that included racialized populist promises to white voters. In particular, he railed against “federal overreach” and high taxes, which he framed as stemming from forced desegregation, legislative reapportionment, and property reassessment.

Yet, despite this populist rhetoric, Wallace’s real concern in terms of pushing low property taxes was helping his corporate benefactors.

Wallace won narrowly, and his deep alignment with corporate interests became evident when he backed a series of what was known as “lid bills.” These laws preserved large landholders’ power and profit margins by fixing property tax assessments and rates at ridiculously low levels and removing local authorities’ ability to change them. They eliminated the power of local Black officials elected after the Voting Rights Act to demand that utility companies and large timber and paper conglomerates pay their fair share.

Read More: The Troubling Consequence of State Takeovers of Local Government

Not surprisingly these industries poured thousands of dollars into these campaigns. With their crucial help, the lid bills passed in 1972 and legislators enshrined the limits they imposed into Alabama’s constitution by 1978.

The lid bills saved these interests millions of dollars and Alabama’s largest landowners quadrupled their holdings.

Passage of the lid bills was a sign of the hollowness of Wallace’s populist rhetoric. The governor had spent years claiming to oppose a “central government meddling in local affairs” — and now he championed doing just that to help corporations.

The practical impact of these policies was devastating on two levels. First, they severely limited the local contribution to things like healthcare and education, resulting in poorer public services. They also forced the legislature to enact one of the heaviest sales tax burdens of any state. The hefty sales taxes disproportionately affected poorer residents, even as companies like Alabama Power saved millions in property taxes.

These policies have hampered Alabama for decades, making it hard to recruit new businesses or keep skilled workers in state. They’ve also strained local governments’ ability to fund essential services and promote economic growth. They highlight the damage that can be done when policy prioritizes corporate interests over the public good.

Trump’s rise to power, like Wallace’s, rests on exploiting divisive social issues and presenting himself as a champion of the “common man.” His promises to create jobs and boost the economy resonate with many working class Americans.

Yet, Alabama’s experience under Wallace presents a stark warning to Trump’s working class supporters: while populist rhetoric may appear to offer a voice to voters who feel disenfranchised and marginalized, the policies that follow from it often fail to serve their needs. Unless the policies of Trump’s second term reverse course from the first, and include significant investment in public services, they may well lead to a race to the bottom — one that hurts Trump’s biggest supporters.

Brucie Porter is a doctoral candidate at Auburn University. Her work focuses on the history of race, education, and policy in the American South. Brucie is a native of Auburn, Ala. and earned her bachelor’s degree from the University of the South.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Leave a comment