Elton John has no address. Visitors to his home are given three names: the name of a house, the name of a hill, and the name of a town, which is near Windsor, as in Windsor Castle, where King Charles III lives.

Admission is granted via a big iron gate that swings silently open to a crunchy driveway, a small turreted gatehouse, a pond with geese, hedgerows, wordless men with wheelbarrows and Wellingtons and, after a little walking, a three-story red-brick Georgian compound. From the outside it has the stately but understated air commonly associated with English gentry. One of the property’s chief treasures is a really old oak tree.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

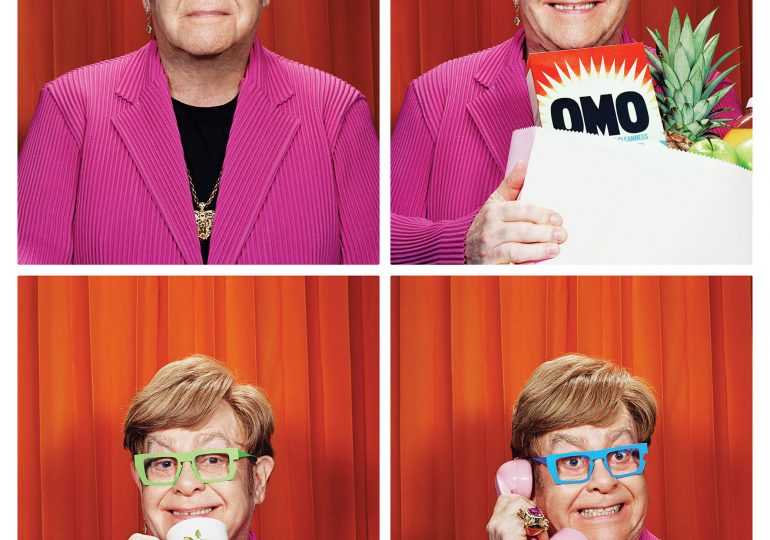

This is not the Elton John most people know. That guy is loud. The glasses, the outfits, the sexuality, the concerts, the retail expenditure, the platform heels, the temper, the parties, and most of all the piano—all set permanently at fortissimo. John has been in showbiz for 60 years, and for 50 of those he has been a front man, inordinately and excessively famous. His triumphs, mistakes, strengths, weaknesses, wigs, and duck costumes have been in full and permanent plumage. The wealth and passions he became known for have not been those associated with aristocracy: they leaned more toward shopping than Chopin.

But these days the comparison to an English noble feels weirdly apt. John’s married with two heirs. His philanthropic work is much admired. Some of his possessions—a selection from his impressive photograph collection—are currently on display at one of London’s most highly regarded art institutions, the Victoria and Albert Museum. His library is full of trophies that attest to his prowess, an Emmy and multiple other awards crowded together on a small table with some ancient sculpture fragments. He has literally been knighted. From his garden, the current King’s grandmother once remarked, you get a good view of the British monarchy’s ancestral home.

John has owned Woodside, as the house is known, for nearly 50 years, but until the pandemic he did not spend much time in it. Most of his life was spent in hotel rooms, while he toured. Like many nobles, he found laundry an unfamiliar task. “It was the most embarrassing thing in my life when I went into [drug] treatment that I couldn’t work a washing machine,” says John during our first interview, conducted in a New York City hotel room in November, while his husband David Furnish lies on the bed and two publicists wait in the bathroom. “I thought, ‘F-ck. Here you are at 43 years of age, and you can’t work a washing machine. That shows you how you’re f-cked up.’”

More than three decades later, at 77, he is doing much more than still standing in front of the top loader. Right now, he’s dealing with damage to his right eye, which was previously the good one, that has rendered him almost blind, but you wouldn’t know it to meet him. The candle that is Elton John has been inextinguishable, no matter how strong the wind. His 57 U.S. Top 40 hits were mostly released during his wild-child youth, but he found a second act in writing songs for animated Disney movies, for which he won two Oscars, and a third in writing songs for Broadway musicals, for which he won a Tony. There’s a whiff of fourth act about him as he moves into the mash-up phase of his career, lending his melodies—and some vocals—to a new generation of performers. It has been a mere 16 months since he had his last hit single, a collaboration with Britney Spears, who hadn’t recorded music for five years.

This kind of longevity requires not just prodigious musical dexterity, and phenomenal luck, but stamina. Few can keep up with fame’s sugar-daddy demands for long enough to get to the settling-down phase with their sanity, health, and friends and family intact. “When you’re famous, there’s like a court around you,” says John. “People are vying for position, and the nearer you are to me, the more people will get jealous.”

He has bested or evaded the four horsemen that cut down his generation’s boldest names: drug addiction, AIDS, irrelevance, and suicide. Apart from Paul McCartney, who had a Top 10 single with a resurrected Beatles song in 2023, very few of John’s contemporaries are still alive, let alone releasing new hits. The Rolling Stones still tour, but their last No. 1 was 40 years ago. John has also survived deep family dysfunction, tabloid fabrication, early hair loss, bulimia, and in the ’80s, a brief marriage to a woman. And here’s the key part: he has remained prolific.

Having performed 4,500-something concerts over half a century, he retired from touring at the end of 2023, but not from cultural output. Never Too Late, the most recent documentary on his life, which compares his meteoric first five years of touring the U.S. with the final tour that ended in July last year, is now on Disney+. He has written the music for and co-produced two new musicals: Tammy Faye and The Devil Wears Prada. An auction of some of his many belongings in February brought in more than $20 million, twice the presale estimate. He has a podcast/radio show, Rocket Hour, which promotes young musicians. This year the 52-year-old song “Rocket Man” hit a billion streams on Spotify, while “Cold Heart,” a 2021 track with Dua Lipa, drew a million listeners a day. “When Elton and David called me about the collaboration, for me, it was because of our friendship,” says Lipa. “And of course, singing alongside one of my musical heroes was a no-brainer. His music has been able to soundtrack my life from the very beginning.”

John’s outrageous string of hits is now a list of global standards. “Do you know how many requests I get a day for the use of our songs on things like America’s Got Talent, The Voice, or the silly show where they dress up as poodles?” says Bernie Taupin, John’s longtime writing partner, who has provided the lyrics to most of his hits. “I don’t think Bob Dylan gets a lot of requests for The Masked Singer.”

In person the glam-rock superstar is gentle, a little shy, and eager to please, and especially eager to make people laugh. While some frailties are apparent, he still has plenty of bounce. He favors comfy designer tracksuits and sneakers. He doesn’t hear too well or walk with confidence. Corrective surgery a few years back made the glasses a mostly cosmetic choice, but a recent eye infection damaged the optic nerve in his right eye and it’s taking a while to heal. His husband is determined to be optimistic about it. “I just think it’s just gonna take time, right?” Furnish says.

It’s the evening after opening night of Tammy Faye, the $22 million Broadway musical about the televangelist Tammy Faye Bakker, who came to embrace and be embraced by the gay community. John wrote the music. The reviews are out, and they are dismal. It will be just one day before the show’s impending closure is announced. John is mostly philosophical. “It’s a shame for everyone who put so much work in it,” he says. “But that’s what happens when you take a chance.” He and Furnish chalk the failure up to the mood after the election of Donald Trump. “It’s a fairly political piece of work,” he says. “And with that you have to press somebody’s buttons. The buttons we pressed last night with the critics weren’t the right ones.”

If John seems sanguine, it’s perhaps because he’s long been more interested in exploring what’s next than stewing about his failures. His best-selling 2019 memoir Me and Furnish’s 1995 documentary about him, Tantrums & Tiaras, reveal a willingness to let people see the less fabulous side of Elton John. “It was a bit like video therapy in a way,” says Furnish. “It gave me a chance to go in with a camera, like a shield, and kind of confront and shine a light on things in his life that I thought were odd.”

The documentary (which George Michael advised him to bury) captures him in full meltdown mode, insisting on one occasion that he will never make another music video because someone left a bag in a car, and on another instructing his private plane to leave the South of France as soon as possible and never return because a woman waved at him during a tennis lesson. (They stay.)

John still struggles with patience. “David can tell you that my fuse is very short, and the worst thing about my temper is that David is very rational about things and he’ll explain,” says John. “And I’ll get even madder about it.” When John met Furnish in 1993, at a dinner party a friend had organized at Woodside at John’s request, Furnish was impressed with the star’s warmth and lack of ego. But as they grew closer, he realized John, who had endured childhood under a distant and eventually absent father and an ill-tempered mother, was a people pleaser with self-esteem issues. “He was very, very shut down in terms of accepting love,” says Furnish. “No one had ever asked him to do personal things like go for a walk together, those kind of joyful things.”

John was one of the earliest celebrities to come out, in 1976, initially saying he was bisexual, when such an admission was deeply hazardous career-wise. After 31 years together, John and Furnish, who formerly worked in advertising, take their gay-icon status very seriously. They formed a civil partnership in December 2005, within weeks of its becoming legal to do so, and were married on the same day nine years later after the U.K.’s same-sex-marriage laws were passed.

Unlike many celebrity parents, they are sending their two boys, Zachary, 13, and Elijah, 11, to school locally, although Zachary just started boarding school. “We deliberately didn’t homeschool our children because we want them to be their own people and to define life as they want to be defined,” says Furnish, who is husband, helpmeet, and manager. He’s the CEO of Rocket Entertainment, is listed as executive producer on the musicals, and is the co-director of the new documentary, which he brought to R.J. Cutler, who has also helmed docs about Martha Stewart and Billie Eilish.

Fatherhood, marriage, and sobriety have mellowed the superstar. As has self-knowledge. “I will flare up if I’m tired, if I’m exhausted, if I’m overwhelmed,” says John. “I don’t like having that temperament, but it’s all usually done and dusted within five or 10 minutes.” But impatience is also part of his gift, it seems. He likes to write fast—if he can’t get a tune for the lyrics he’s given in an hour or so, he moves on to new ones. “I know people think, ‘Oh, God, he doesn’t work that hard,’” says John. “But it’s really effortless. If I get a lyric and I look at it, the song comes straight out.”

Taupin wrote “Your Song,” the duo’s most commercially successful tune, over breakfast when he was 19 and living with John’s family, sleeping in bunk beds in John’s room. He guesses it took his roommate half an hour to create music for it. “We have a telepathy between the two of us,” says John of Taupin. “He seems to know what I want, and I seem to know what he wants. It’s really unusual and it’s very spooky.” In the new documentary there’s old footage where John explains how he scored a song Taupin wrote. “As soon as you see the word ballerina, you know it’s not going to be fast, it’s got to be gentle,” the young star says, like it’s the most obvious thing in the world. The song is “Tiny Dancer.”

In some of rock ’n’ roll’s most formative years, 1970 to 1975, John released 13 albums, seven of which went platinum. He was the first artist ever to have an album debut at No. 1 on the American charts and is the only one ever to have had a Top 10 single in each of the past six decades. Even today, John’s songs are inescapable—they’re at every party, in every restaurant, in every airport, on every hold for an agent, at every karaoke night. Spears cited him as her favorite artist even before their duet gave her an unexpected hit song. “Elton’s songs are perfectly, masterfully written songs, and that’s what connects them to millions, billions of people,” says Chappell Roan, whom John raves about and whose rapid rise to fame is reminiscent of John’s early days.

Roan says he also helped her learn to trust her instincts. “The advice he gave me was that the songs will come,” says Roan. He told her that after his first album blew up, he had no songs lined up. “He thought that he wouldn’t have the ideas, but they were absolutely there. He just had to let them come to him. So that’s a good reminder.” As well as being a guru for young performers, John has restored the careers of older musicians who had lost faith in themselves. His work with John Lennon gave the Beatles legend a No. 1 hit. And he rescued one of his idols, Leon Russell, from obscurity with an album they made together in 2011.

Rocket Hour is mostly just him playing music and telling the young artists how much he adores them. The people he interviews look bewildered to be so feted, like they got a FaceTime about their science project from Albert Einstein. “Elton’s impact cannot be overstated, and even now, his continued effort to make a better future for young LGBTQ+ artists is so felt,” wrote Allison Ponthier, one of the artists he has featured, on social media.

For Taupin, John’s enduring relevance is a validation. “What people didn’t realize in the ’70s and ’80s and ’90s, but I think they realize now, is that he’s one of the best f-cking piano players on the planet,” he says. “There are a lot of people that have great catalogs and great songs, but I don’t think anybody of our peers has songs that are so varied.” Cutler, the documentary’s other co-director, calls him “Mozartian in his prodigious gifts.” In his youth, Cutler forged multiple record vouchers to win a ticket to John’s 1974 concert at Madison Square Garden. “It comes out of him,” says Cutler, trying to describe John’s artistry. “It emanates from him, like it’s a gift from the heavens.”

Music was always the easiest part of John’s life. Words—and relationships—not so much. A fledgling music producer at Liberty Records was so unimpressed with young Reginald Dwight’s songs during an audition that he sent him packing, handing him an envelope of lyrics mailed in by a 17-year-old chicken farmer from Lincolnshire as he left. It’s one of the greatest origin stories in rock history. The unlikely duo of John and Taupin churned out hits in much the same way chickens make eggs, often and without fuss. Except these eggs frequently turned platinum.

While the songs were appealing, it was John’s performance style that captivated American critics on his first tour in the States in 1970. He had developed an approach to the piano that combined the merriness of Winifred Atwell with the force of Jerry Lee Lewis and the showmanship of Little Richard, all to a rock beat. The costumes and keyboard antics were brazen, but the stories the songs told and harmonies they used were mostly tender. “I think there’s always a new generation that cling on to the things they say,” says Taupin.

Somewhere around 1974, at the peak of his productivity, John was introduced to cocaine by his ex-lover and then manager John Reid. He took to it with the avidity he applies to most of his pursuits. At first he found it freed him of his crippling shyness, but eventually it took over. “You make terrible decisions on drugs,” he says. “I wanted love so badly, I’d just take hostages. I’d see someone I liked and spend three or four months together, and then they would resent me because they had nothing in their life apart from me. It really upsets me, thinking back on how many people I probably hurt.”

As John became increasingly dependent on drugs, the music got worse. “I was terrified for him. It was absolutely horrible,” says Taupin. He had some hits—“I’m Still Standing,” interestingly, came out of this period—but they were rarer. “A lot of the work that we did in the times when he was at his worst wasn’t the best of both of us,” says Taupin, who says watching John’s decline made him reform his own heavy drug use. “I wasn’t able to creatively invest any time in writing material that related to him until he actually found himself, and then it was easier for me to reflect upon it.”

John now divides his life into pre- and post-sober periods. He has helped many people kick drugs and has offered to help many more. He is Eminem’s sponsor. He orchestrated English pop star Robbie Williams’ first stint in rehab. He tried, without success, to help George Michael. “It’s tough to tell someone that they’re being an a–hole, and it’s tough to hear,” he says. “Eventually I made the choice to admit that I’m being an a–hole.” Those struggles have made him doubt the wisdom of legal weed. “I maintain that it’s addictive. It leads to other drugs. And when you’re stoned—and I’ve been stoned—you don’t think normally,” he says. “Legalizing marijuana in America and Canada is one of the greatest mistakes of all time.”

Asked if he feels the same way about alcohol, he pauses, exhales, and asks Furnish for help. His husband, who is also sober and has already prevented the star from oversharing once during the interview, sits up on the bed and offers a balanced answer, suggesting that while alcohol is part of the fabric of society, there are studies that find it’s much less healthy than people believe it to be.

Survival, as the poet Christian Wiman has said, is a style. You have to be around long enough to really make a dent on the culture. John, who has taken a half-hearted bid at ending his life three times, thinks there were three things that saved him from the fates that took so many of his peers: Watford FC, a soccer club local to where he grew up that he bought and took to the Premier League; Alcoholics Anonymous; and a hemophiliac teenager from Indiana named Ryan White. At the club he met people who cared more about soccer than his fame, AA’s methods helped him deal with his multiple addictions, and White, who contracted HIV from a tainted blood transfusion in the early days of the AIDS crisis and was shunned by his school and neighbors, showed him how selfishly he was living.

John heard about White when the teen was invited to an AIDS benefit and said on a TV news program that the person he was most looking forward to meeting was the rock star. John saw the interview and called the family. White, who was given six months to live when he got his diagnosis, survived five years and spent much of it trying to educate people about AIDS. John kept in touch and helped the family out when they needed it. Eventually he flew them to a concert in California. “Elton wasn’t afraid to be around us and just brought so much joy,” says Jeanne White Ginder, Ryan’s mother. “It took us off all the negativity we were facing at home.”

White died on April 8, 1990, at 18. John was at the hospital with him. “It all came to a climax, really, at the Ryan White funeral in Indianapolis—a really sad and emotional week—and I came back to the hotel thinking I’m just so out of line,” John says. “It was a shock to see how far down the scale of humanity I’d fallen.” Six months later he went into rehab. Two years later he started the Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF), of which Furnish is now the chairman. “We could end AIDS tomorrow if every person knew their HIV status and had access to treatment,” says Furnish.

In 2022, President Joe Biden surprised John with the National Humanities Medal, calling him “an enduring icon and advocate with absolute courage, who found purpose to challenge convention, shatter stigma, and advance the simple truth that everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect.” John and Furnish are particularly proud of the EJAF-funded program that allows people to take HIV tests at Walmart, without going to a doctor. They believe that the U.N.’s goal of ending new AIDS cases by 2030 is achievable, even with an incoming U.S. Administration whose proposed health czar has suggested, contrary to evidence, that AIDS is not caused by a virus.

Looking back on that news program that first brought John into their lives, White Ginder recalls how horrified she was that her son had not talked up the event’s sponsor Elizabeth Taylor. “I said, ‘Ryan, why did you mention Elton John?’” she says. “And he said, ‘Because he’s not afraid to be different.’”

As Furnish and John sit on floral couches next to a gas fireplace in Woodside and talk about the demands and benefits of being Elton John, it is clear that the rock star gave up touring reluctantly. (“Elton used to say, ‘I want to die onstage,’” says Furnish. “It never made me particularly happy.”) But what he has now is what he has always wanted: a home. Yes, it’s one where a stunning young man serves hot beverages and where artworks by Damien Hirst and Andy Warhol share space with a mannequin covered in what look like jelly beans. But the bougie-candle-scented living room is also strewn with family photos. As with so many who resisted the pulls of fatherhood until late in life, John’s chosen style of parenting is gushy. “On my gravestone,” he tells me in our New York City interview, “all I want it to say is ‘He was a great dad.’”

There were casualties to creating this new life, the biggest of which was his relationship with his mother, to whom he had been very close. “She meant a lot to me, but my success changed her,” he says. He continued to support her financially, but she disapproved of Furnish. “She was probably one of the biggest liars I’ve ever met,” says John. “But that’s because she was a sociopath, and I got to understand it.” The two fought publicly; she hired an Elton John impersonator for her 90th birthday. Her son and his spouse were not invited, but reporters were. “I rang her up the next day to wish her a happy birthday. I said, ‘How did it go?’” John recalls. “And she said, ‘It was great. He’s as good as you are.’”

Perhaps it’s age or his relationship with Furnish (or distance from his mother, who died in 2017), but he has grown slightly more comfortable with himself. Slightly. His distaste for being on video, for instance, persists. “Music videos should be made by good-looking people like Harry Styles,” says John. “I’m not very good at looking at myself. I don’t think you ever lose that body consciousness. I just think it stays with you forever. But I am much better.” He especially dislikes TV and has turned down invitations to be a judge on the TV talent shows that request his music so often. “Being on TV all the time kills your career, kills your vibe, kills your charisma totally,” he says.

He would prefer to spend his time discovering. “I’ve never lost the excitement of buying a new record, a new book, a new photograph,” he says, noting that if he had to choose between never playing music again and never listening to it again, he’d opt to keep listening. “I just think that’s kept me going,” he says. But he is beginning to think a bit about what lies beyond. “I don’t really believe in the biblical God too much, but I have faith,” says John. “My higher power has been looking after me all my life; he’s got me through drugs, he’s got me through depression, he’s got me through loneliness, and he got me sober. He’s been there all the time, I think. I just didn’t acknowledge him.”

Like many megastars, John feels that he was somehow chosen to be as famous as he is, because he could withstand the burdens it brings. Asked if he’d wish his talent on his sons, if it also came with the drawbacks of stardom, he offers an emphatic no. “I’ve lived an incredible life, but it’s been a hell of a life, and it’s been a slog,” he says. “I wouldn’t want that amount of pressure on them.” Icon status is great, but as he learned over his many decades in the spotlight, there’s more to life than rock ’n’ roll. “If people remember that we tried to change the world a little bit, we were kind, we tried to help people,” that would be enough of a legacy for him, says John. “And then, apart from that, there was the music.”

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein

Set design by Trish Stephenson; styled by Jo Hambro; grooming by Jamie Madison; production by 2b Management

Leave a comment