The presidency of Jimmy Carter, who died on Dec. 29 at age 100, is typically understood as bland and ineffective—perhaps best symbolized by the uninspiring cardigan sweaters he favored wearing in office.

Four decades of subsequent good works have transformed Carter’s cardigan into a symbol of something more wholesome, humble even. Carter’s post-presidential authenticity has even attracted a young, left-leaning fan base, like those using the TikTok hashtag #jimmycartergotmepregnant as a mock ironic lament about the declining quality of recent presidents.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

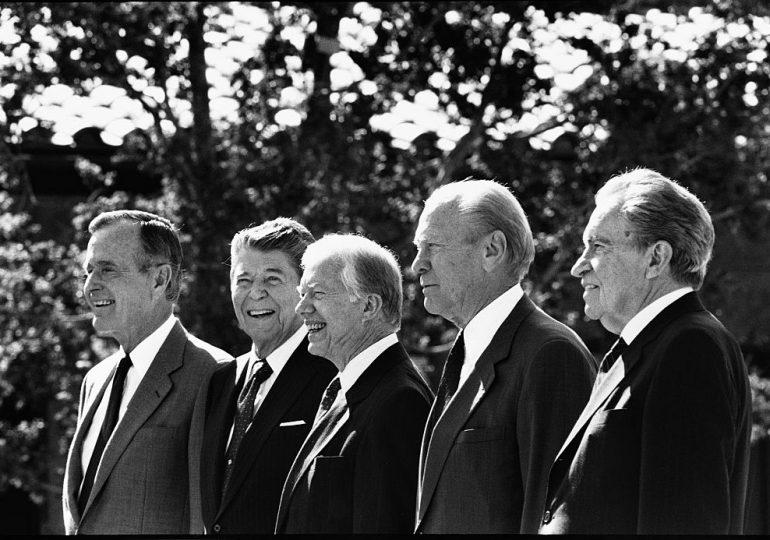

Yet, both portraits miss the mark. Carter was neither as ineffective a president as his critics allege, nor as liberal a politician as his new fans believe. Instead, the 39th president scored enormous policy successes—but observers often missed them because they didn’t grasp that Carter was one of the most substantively conservative presidents of the last half-century. In some ways, Carter actually did more to push American economic policy to the right than his Republican successors Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump. Understanding this reality paints Carter’s presidency in a totally different light.

Carter often described himself as a “conservative progressive,” which he defined as being “a fiscal conservative, but quite liberal on such issues as civil rights, environmental quality, and helping people overcome handicaps to lead fruitful lives.” Carter’s fiscal conservatism was perhaps natural for a successful, sophisticated agribusinessman.

During his 1976 presidential campaign, Carter stumped on the proposition that Washington was a “confused, bloated bureaucratic mess.” If elected, he pledged to streamline government agencies and reduce spending just as he had as governor of Georgia. This was not mere campaign rhetoric that disappeared once Carter entered office. In his 1978 State of the Union address, Carter said, “Government cannot solve our problems …[or] eliminate poverty, or provide a bountiful economy, or reduce inflation, or save our cities, or cure illiteracy, or provide energy.” It was an applause line one might have expected from a stalwart conservative Republican, not a Democratic president.

Unsurprisingly, Carter’s conservatism alienated much of the Democratic left. Looking back on his presidency in 1982, one union leader remarked, “As presidents go, he [Carter] was on par with Calvin Coolidge.” It was a fitting comparison for a president who once bragged that his policies represented “the greatest change in the relationship between business and government since the New Deal.”

Carter’s conservatism ran deeper than mere rhetoric. He transformed government regulation of the economy more than any other modern president. It was Carter, not Reagan, who was the true “Great Deregulator.” Carter viewed deregulation as the solution to stagflation, the unprecedented economic challenge confronting America in the 1970s. During his presidency, inflation rose from 6.5% to 13.5%, even as unemployment reached eight percent by the time he left office. And Carter blamed excessive regulation for these economic headwinds.

Not all of his deregulatory push generated opposition from the left. Deregulation of certain industries, especially trucking and airlines, even garnered support from Carter’s most prominent liberal critic and 1980 primary challenger, Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.). At the 1980 Democratic Convention, Kennedy bragged that his party had “ended excessive regulation … and we restored competition to the marketplace.” Kennedy’s views angered the labor unions who had long backed him in Massachusetts, but he believed that making himself the congressional face of deregulation would improve his national, presidential appeal.

That calculus explained why Kennedy and Carter joined forces to unshackle the airline industry. Carter appointed the economist and deregulatory hawk Alfred Kahn to the Civil Aeronautics Board, which created pressure on Congress to pass Kennedy’s legislation ending government regulation of flight routes and ticket price controls.

Carter’s success with airline deregulation in 1978—and Republican pickups in the midterm elections—lowered the political barriers to further deregulation. Carter pounced on the opportunity and went far beyond what liberals found tolerable. The administration worked to free scores of industries, from energy to trucking to rail, in subtle, yet significant ways. For example, after passage of the Motor Carrier Act of 1980—which allowed trucking companies to choose their own routes—500,000 new truckers flooded the market. The new efficiencies and additional competition ultimately reduced carriage costs by a third, benefiting every category of good produced or sold in America.

The positive impacts of these moves are often credited to Carter’s successors because the benefits only became evident after he had left office. But in concrete ways, he helped lay the foundation for the economic prosperity of the 1980s and 1990s.

Yet, perhaps the most underrated front in Carter’s war on regulation reshaped broadcasting, politics, and entertainment. Charles Ferris, Carter’s Federal Communications Commission Chair, was a zealous deregulator, who called the FCC’s thicket of regulations “ossified” and a “dead shell.” He repealed regulations that had stunted cable television’s growth, and acquiesced to the courts limiting FCC oversight. As a result, cable grew rapidly; by the mid-1980s, the share of households with cable subscriptions had tripled to nearly 60 percent.

Ferris also slowed enforcement of the Fairness Doctrine—a rule meant to promote balance in political broadcasting—which had been weaponized by the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations against political opponents. By streamlining the station license renewal process, Ferris also made it far harder for activists on both sides of the political spectrum to use the doctrine to threaten broadcasters. While it was Reagan’s FCC that did away with the Fairness Doctrine—something for which many on the left still curse him—it simply put the finishing touches on Carter’s revolution.

These deregulatory moves transformed news and entertainment, making everything from HBO to cable news channels to hit shows like The Sopranos and The Daily Show possible.

Read More: Jimmy Carter Was More Successful Than He Got Credit For

Carter’s deregulatory campaigns therefore reshaped the American economy, the media landscape, and national politics in seismic ways.

If he had been a Republican, he might rank higher than a subpar 26th (out of 44) in presidential rankings, perhaps even neck-and-neck with the ninth place Reagan. But he was too conservative for his most progressive allies and his policy stances soon became far out of step with a rapidly homogenizing Democratic Party. Meanwhile, Republicans—who were ideologically more amenable to Carter’s laissez-faire policy accomplishments—were not predisposed to recognize the achievements of a member of the opposition.

Yet, Carter’s conservative victories compare favorably to the accomplishments of his Republican successors. Reagan decreased the power of unionized air traffic controllers; but Carter deregulated the entire airline industry with profound results. Americans today fly four times as many miles at less than half the cost per mile as they did when Carter was president, while as many Americans now fly each year (an average of 49% from 2015-2019) as the percentage in 1971 who had ever flown before.

Similarly, George H.W. Bush sent troops to Kuwait to protect U.S. oil imports; but Carter cut American dependence on foreign oil imports nearly in half by deregulating the energy sector and encouraging domestic production. George W. Bush massively expanded the federal education bureaucracy with the No Child Left Behind Act, while Carter cut entire federal agencies, like the Civil Aeronautics Board. During Trump’s presidency, the federal debt to GDP ratio broke the record previously set during World War II, whereas Carter reduced that ratio to its lowest point since the beginning of the New Deal.

For good or ill, Carter remains the most substantively conservative president of the last half century—even though neither his champions or critics recognize it.

Paul Matzko is a historian and a research fellow at the Cato Institute. His book, The Radio Right: How a Band of Broadcasters Took on the Federal Government and Built the Modern Conservative Movement was published in 2020 by Oxford University Press.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

Leave a comment