For nearly half a century, NASA has been talking an awfully good game about its much-heralded Mars Sample Return (MSR) project. As long ago as 1978, the space agency requested funding to develop a mission that would see an uncrewed spacecraft land on the Red Planet, collect and cache samples of rock and soil, and bring them back to Earth for study—all without the risk and expense of sending human crews out to do the spelunking. But tight budgets and challenging technology meant that it was not until 2009 that NASA, in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), finally got the mission rolling.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

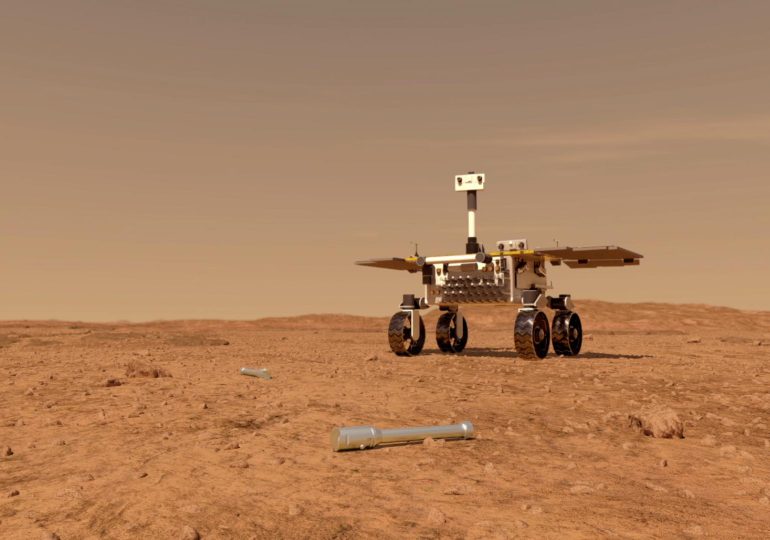

Even then, it would take 12 years for the first phase of MSR to at last fly. On Feb. 18, 2021, NASA’s Perseverance rover landed on Mars and began collecting soil, rock, and atmospheric samples in 30 sterile, cigar-sized, titanium tubes. Now, four years later, the entire mission—generations in the making and billions in the funding—may be coming undone.

During a Jan. 7 press conference, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson conceded that costs have exploded, deadlines have unraveled, and unless MSR receives a major rethink now, there may be neither will nor wallet to fly the long-awaited mission to collect the Mars rover’s sample tubes.

“As that plan had proceeded, it continued to be delayed as to when we would get the samples back, and the cost began to accelerate to the point that earlier this past year, it was thought that it could be as much as $11 billion and you would not even get the samples back till 2040,” Nelson says. “Well, that was just simply unacceptable.”

Though Nelson declared flatly that he had as a result, “pulled the plug on [the mission] as it’s currently envisioned,” things are not quite that grave. Last April, NASA went quietly seeking private partners, including SpaceX and Blue Origin, which could help provide hardware and defray costs. Whether MSR indeed reaches fruition, the project’s current woes are a cautionary tale of what happens when a mission gets too complex and too costly, with incomplete planning being done before hardware actually begins flying.

MSR was by no means the only job Perseverance has had on Mars, and the rover has been an unalloyed success so far in studying soil, atmosphere, and terrain. But getting samples back to Earth was nonetheless one of its major goals. The biggest problem with MSR was always that it simply had too many moving parts. In a perfect and parsimonious world, a single two-stage spacecraft would land on Mars, scoop up soil samples in situ, and transfer them to an ascent stage which would blast off into orbit. There, the samples would be transferred again, this time to a second orbiting spacecraft, equipped with an Earth-transit module which would carry the soil and rock back home. Colloquially called a grab-and-go mission, this is the flight profile China is planning for its Tianwen-3 mission, now scheduled for launch to Mars in 2028.

The downside of grab-and-go is that you get just one sample from one site, which limits the science you can do. NASA has instead sent Perseverance to multiple spots around its Jezero Crater landing zone—a site that billions of years ago was an inland sea that may have hosted life. There the rover has collected samples from different elevations with different chemical makeups and left the titanium tubes tubes scattered in its path like geological Easter eggs.

“To find different samples of different layers showing different ages of material and rocks,” says Nelson, “it’s going to give quite a history of what Mars was like billions of years ago, when there was water in the lake.”

The problem is, bringing those samples home required multiple other spacecraft, none of which have been firmly designed or contracted yet, much less built. For starters, scattering the samples requires collecting the samples, which calls for another fetch rover, able to follow in Perseverance’s path, gather up the tubes, and then transfer them to yet a third lander capable of taking off from the surface, and transferring the tubes to a fourth orbiting transit ship, built by the ESA, that would bring the tubes home. Not only did that break the bank at $11 billion, it also broke the schedule, with the collection and return phase not happening until the mid to late 2030s. And none of that was helped by the fact that NASA saw a total $5 billion budget cut over the 2024 and 2025 fiscal years, slowing R&D even further.

“This thing had gotten out of control,” says Nelson. “You simply can’t do everything you want to do with less dollars.”

But if MSR as originally envisioned is dead, MSR as an ultimate goal isn’t. NASA is currently seeking private company solicitations to land the fetch vehicle and ascent vehicle on Mars, taking advantage of competitive pricing that could assign the job of sending the surface hardware to Mars to a SpaceX Falcon Heavy booster, which has had a total of 11 launches, or to a Blue Origin New Glenn booster, which scrubbed a planned maiden launch on Jan. 13 due to technical issues and has not yet rescheduled its next attempt. The two rockets’ propulsive muscle would allow them to land relatively heavy collection and ascent vehicles on Mars.

The other alternative involves NASA keeping more of the work in-house. Like the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, the sample collection vehicle and Mars ascent vehicle could be landed on the surface by a “sky-crane,” a rocket-powered chassis that hovers about 20 meters (66 ft.) above the Martian surface and lowers the vehicles to the ground by cable. The limited power of the sky crane would require a smaller, lighter—not to mention cheaper—collection vehicle and ascent stage and allow for a smaller, cheaper booster to get the mission started. Under either scenario, the ascent vehicle would still rely on an Earth-transit ship built by the ESA to carry the samples home. Both missions would cost somewhere between an estimated $5.8 billion and $7.7 billion.

“That’s a far cry from the $11 billion,” says Nelson.

Flying cheaper means flying sooner—at least a little—with Nelson projecting that the missions could begin as early as 2030 when the European return vehicle would launch, followed in 2035 by the fetch vehicle and the ascent vehicle.

Politics, as ever in a federally bankrolled program, will play a role in all of this. Nelson and the outgoing NASA team have not yet discussed Mars Sample Return with Jared Isaacman, President-elect Donald Trump’s choice for the next NASA administrator, much less with Trump himself. But Nelson remains hopeful.

“We have not had those conversations,” he says, “but I think it’s a responsible thing to do if they want to have a Mars Sample Return [and] I can’t imagine they don’t. I don’t think they want the only sample return coming back on the Chinese spacecraft.”

Leave a comment