Director Charlie Shackleton thought he could have his cake and eat it too.

For years Shackleton had been considering the idea of making a documentary centered on the Zodiac Killer. The mysterious and legendary serial killer haunted the Bay Area in the late 1960s and has been a fixture of pop-culture fascination ever since, from David Fincher’s 2007 thriller starring Jake Gyllenhaal to last year’s Netflix doc This Is the Zodiac Speaking.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“I had a sort of general love-hate relationship with true crime,” he says in a video call. “It seemed like the way to make something that would genuinely interest me but could also potentially be quite commercial.”

Shackleton, whose previous features include the essay-like Beyond Clueless about teen movies and Fear Itself about the horror genre, found his angle when he came across the book The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge. Published in 2012 by Lyndon Lafferty, a California Highway Patrolman, the book hones in on a suspect he calls George Russell Tucker and chronicles how Lafferty believed his efforts to bring Tucker to justice were thwarted. Alas, Lafferty’s family did not grant Shackleton the rights to The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up.

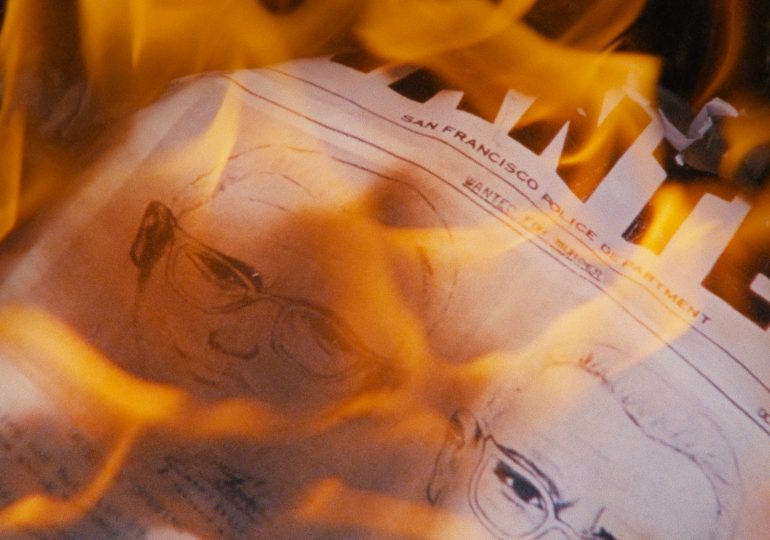

So instead, Shackleton made Zodiac Killer Project, which premiered on Jan. 27 at the Sundance Film Festival. This documentary is about the documentary that Shackleton would have made had he secured those rights, and in turn serves as a deconstruction of the entire genre of true crime and how filmmakers in his position often manipulate their audiences. Shackleton narrates, with a charming British accent and a wry sense of humor that veers into the self-deprecating, how he would have approached Lafferty’s tale. Instead of the reenactments he might have staged, the images on the screen are largely static shots of California locations mostly devoid of people.

Read more: The Human Cost of Binge-Watching True Crime Series

Shackleton also steps back to reveal how his movie might have adhered to the tropes of the true crime genre. For instance, how the title sequence would have used “country-inflected music, but with a sort of dark edge” as it cycles through layered images of landscapes and shadowy men. He uses examples from shows like The Jinx and Making a Murderer. He introduces us to terms like “evocative b-roll,” the kind of stock footage of, say, cigarettes burning or ominous-looking out-of-focus figures that get the blood pumping.

“I was never blind to the many complex ethical lapses of these things,” Shackleton explains. “And it wasn’t, I suppose, until I got my hands dirty, as it were, that I began to engage with those questions more actively.”

The idea for what Zodiac Killer Project eventually became emerged from conversations Shackleton had with friends, the kinds of chats he would have at a pub. Despite the fact that he legally couldn’t make a movie based on Lafferty’s book, he couldn’t let the idea go.

“I started from thinking about how it would be to have me tell it as I had already so many times to friends,” he says. “But obviously I was working within the restriction of not being able to adapt the book. Not being able to have any of the content of the thing. So what was left without the content? It was just like the shape and the feelings that I was convinced people would have felt if only I could have done the thing.” This led him to the idea of empty images of locations. If he couldn’t tell the whole story, what was left but absence? Sounds dull, yes? It’s not, though, because Shackleton makes the lack of action oddly hypnotic, allowing you to fill in the spaces with his intelligent, often funny descriptions of what might have been.

Read more: 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

But the shape the Zodiac Killer Project ultimately took proves fascinating in the way Shackleton calls himself out for the ethical leaps he might have taken. He acknowledges that there’s a certain degree of exaggerated “glibness” in the way he talks about what he might have done, and that he doesn’t know how far he would have actually gone in terms of salacious liberties taken. Still, he casually notes, calling out his own hypocrisy, he doesn’t show the house of Lafferty’s Zodiac suspect because it didn’t look spooky enough for the lair of a potential murderer, especially based on the way Lafferty describes it in the text. The completely unrelated building Shackleton shows is eerily shrouded in trees, unlike the real thing.

“I think if you make documentaries, when you watch documentaries, you have quite a heightened awareness of where those sorts of deceptions are happening because you’re watching with an eye on how it’s been made,” he says. “It appealed to me to kind of wrap the entire audience into that scrutiny so that they could scrutinize my choices just as I would anyone else’s.”

However, Shackleton was also careful not to call out viewers for being attracted to true crime, or shame them for liking exploitative stories of blood and guts. In fact, he believes that true crime itself has co-opted that narrative, scolding while still trying to offer up all the addictive material of the genre. During Zodiac Killer Project, he specifically calls out the highly watched and highly criticized Jeffrey Dahmer installment of Ryan Murphy’s Monster franchise, showing how the series offers up hours of Evan Peters as Dahmer committing heinous acts, while simultaneously asking for respect for Dahmer’s victims.

“Whatever value that analysis might ever have had has been completely cannibalized now by the true crime industry,” he says. Instead, Shackleton wants to turn the lens on the industry itself.

He adds that the other part of the equation is the question of supply. “The streamers and everyone else are constantly saying, ‘Well, this is what viewers want, there’s a huge demand for this so we just make it. But of course they are also putting out so much of it that often it’s just the thing that’s there when you pull up Netflix.”

Shackleton is not dismissive of all true crime. When asked to point out a documentary that he thinks does the style well he calls out Errol Morris’ seminal 1988 film The Thin Blue Line, about the wrongful conviction of Randall Dale Adams, accused of killing a police officer. “It holds up perfectly,” Shackleton says. “It set the mold of all these cliched shots that I’m taking the piss out of in my film but obviously when it was doing it they weren’t cliches.” But he says he struggles to think of a recent true crime documentary he thinks gets a clean bill of ethical health.

So has making Zodiac Killer Project killed Shackleton’s desire to make a real true crime doc himself? Yes, likely.

“I think my confidence that it’s possible to both lean into that genre and also make something interesting has reduced over time,” Shackleton said. “Not that it wasn’t formulaic before, but it has become so formulaic in the last couple of years, at least by my experience of watching all this stuff that comes up on streaming, that I think I’d be a lot less confident I could have my cake and eat it.”

Leave a comment