Fourth anniversaries aren’t often causes for celebration. But in the case of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which launched on Dec. 25, 2021, this anniversary marks an important transition.

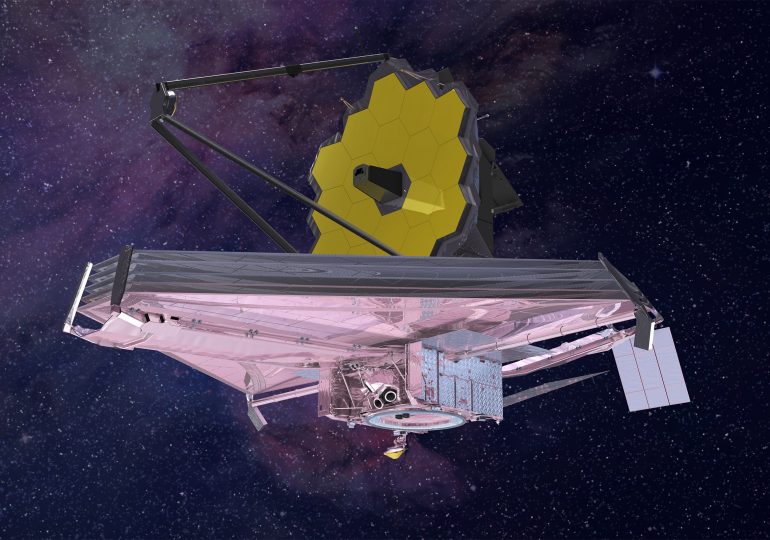

Until now, JWST has been in discovery mode. A generation in the making at a cost of $9.7 billion, it is the most powerful telescope in history, capable of observing at distances and levels of detail without precedent.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But as with any major new scientific instrument, astronomers needed to see JWST in action before they could answer the fundamental question that will drive research for decades to come: How much of our universe can we see?

The JWST builds on the progress the Hubble Space Telescope has made since its own launch, in 1990. The Hubble primarily observes space through the visible region of the light spectrum—the part that our eyes have evolved to see. JWST, however, sees primarily in the infrared, allowing it to penetrate cosmic dust, observe cooler objects, and peer into the early universe.

Because the speed of light is finite, observing objects at greater and greater distances means seeing farther and farther into the past. And because the expansion of the universe—the expansion of space itself—has stretched the visible light from the most distant objects into the infrared, JWST can search for the first sources of light, about 100 million years after the Big Bang.

Four frontiers

Edwin Hubble, American astronomer and the namesake of the Hubble Space Telescope, wrote in 1936 that “The history of astronomy is a history of receding horizons.” NASA, with assistance from the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, has identified four such horizons, frontiers which they designed JWST to cross.

First is the frontier that Galileo traversed in the early 17th century, when he pointed a primitive perspective tube (what we would call a telescope) at the night sky and bridged the ancient, previously impassable gap between the terrestrial and the celestial. In discovering evidence that the Earth orbits the Sun, rather than the other way around, Galileo implicitly recast Earth as simply one more member of a system of planets.

Now, thanks to JWST, the deep history of the solar system is coming into focus. By studying the surface chemistry of scores of icy objects far beyond Neptune, the most distant planet, JWST researchers can trace the emergence and evolution of the solar system as a whole. Meanwhile, the discovery of water among asteroids—a belt of “debris” between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars—raises the possibility that comets weren’t the only objects seeding the Earth’s primordial atmosphere with the ingredients for life.

But our Sun is just one star. Beyond the horizon of the solar system lie the hundreds of billions of other stars in our Milky Way galaxy, many of them hosting planetary systems. Astronomers are using JWST to sample systems in various stages of development—from primitive “protostars” that are first gathering the gas and dust that will eventually coalesce into a disk of orbiting objects, to fully mature planetary systems like our own. Or unlike our own.

JWST has discovered, in one planetary system after another, a kind of planet that is alien to our own system. Our system has historically been divided into two categories: gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) and diminutive rocks (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars). But thanks to JWST, we now know that other planetary systems include variants that astronomers call a mini-Neptune (gas surrounding a rocky core) or a super-Earth (perhaps a former mini-Neptune that has shed its atmosphere).

But our Milky Way is just one galaxy. Beyond that horizon—as Hubble the astronomer himself discovered in the 1920s—lie other galaxies. As with planetary systems in the Milky Way, astronomers are also using JWST to sample galaxies across the universe that are in various stages of development, from clouds of gas, to collisions of clouds of gas, to births of stars, to deaths of stars. Some of those deaths—exploding stars, or supernovae—might help explain a problem that has been puzzling astronomers for half a century: The universe seems to contain more dust than astronomers can account for, yet that dust has to be coming from somewhere. Might that source be supernovae? Preliminary studies have been promising.

Supernovae themselves offer another clue to the evolution of the universe. Scientists have known since the 1950s that successive generations of supernovae, due to thermonuclear forces ripping apart and rearranging the basic building blocks of matter, create heavier and heavier elements. From its inception, JWST’s ultimate goal has been to find the first, “pristine,” galaxies, free of all elements except hydrogen and helium. In order to do so, JWST would have to pass the horizon that the visible-light Hubble Space Telescope itself couldn’t cross: a cut-off around one billion years after the Big Bang.

So far, JWST has been able to observe galaxies, supernovae, and black holes as far back as 300 million years after the Big Bang. Though that might seem like a long period of time, it’s just a blip in a universe that’s 13.7 billion years old.

And JWST researchers are just getting started. They expect the JWST project to last well into the 2040s. That’s a lot more anniversaries. We should hope they’ll all be as deserving of celebration as this one.

Leave a comment