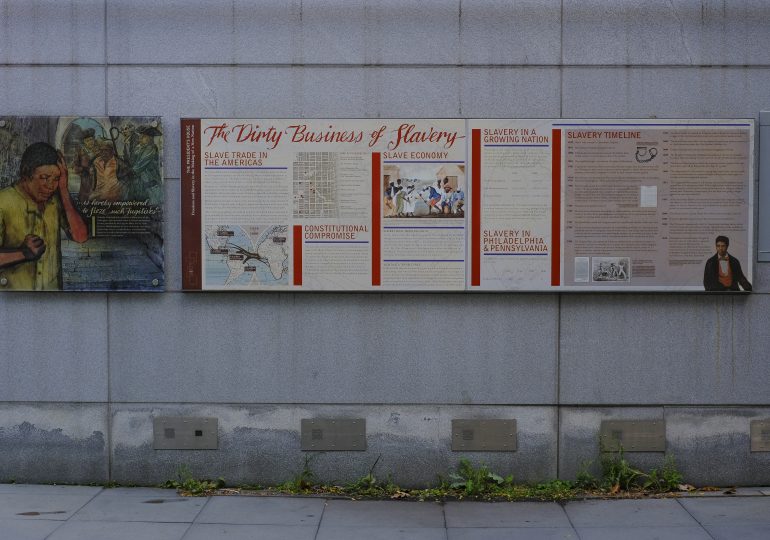

On Jan. 22, National Park Service staff tore down an outdoor exhibit on the history of slavery at the President’s House in Philadelphia, part of Independence National Historical Park. The removal comes after months of conjecture and protest over whether and how the site—which tells the story of the nine people George Washington enslaved while president—would reconcile its content with President Donald Trump’s 2025 executive order demanding the removal of history that might “inappropriately disparage” famous Americans.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

This latest act of historical erasure comes amid heightened scrutiny of slavery’s place in Washington’s legacy in recent years. During the demonstrations for racial justice in 2020, protestors across the country defaced and tore down statues of Washington, arguing that enslavers should be reviled, not honored. Predictably, others pushed back, demanding that we continue to celebrate him as our national hero.

Though many Americans emphasize that we must acknowledge Washington’s involvement with slavery to fully understand his legacy, the Trump administration and many of his conservative allies remain unwilling to even acknowledge Washington’s flaws. In 2024, Trump told an audience, “You know, they thought he had slaves. Actually, I think he probably didn’t.”

Yet for all their intensity, today’s arguments about Washington are hardly new. In fact, disputes over how to acknowledge our first president’s relationship with slavery are as old as the nation itself. For the last 250 years, Americans have treated Washington as an endlessly flexible symbol, one they could celebrate, distort, or wield to serve the needs of their own moment.

Despite efforts to simplify or ignore it, Washington’s involvement with slavery was complicated. He enslaved more people than any of his fellow founders, and he was actively, intimately involved in every aspect of the institution. Yet Washington also privately expressed uneasiness over his entanglements with slavery, and a desire to see it gradually abolished, though he never shared those views publicly.

On his deathbed, Washington used his last will and testament to free the people he enslaved. Although that emancipation came with conditions, it remains true that at the end of his life, Washington freed 123 people from slavery.

This ambiguous legacy as both enslaver and emancipator has troubled Americans ever since.

Even during his lifetime, Washington faced criticism for holding slaves. In 1775, British essayist Samuel Johnson criticized America’s founders, many of whom held slaves: “How is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

In 1797, British abolitionist Edward Rushton wrote a letter directly to Washington, crying “Shame! Shame! That man should be deemed the property of man, or that the name of Washington should be found among such proprietors.” Yet Rushton also understood why many Americans couldn’t recognize Washington’s hypocrisy: “Man does not readily perceive defects in what he has been accustomed to venerate.”

Shortly after Washington’s death in 1799, it was Richard Allen—a preacher born into slavery who later became the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal church—who first told Americans that Washington had freed the people he enslaved. Weeks before the will became public, Allen urged his Philadelphia congregation to mourn Washington’s passing, praising him for having “dared to do his duty, and wipe off the only stain with which man could ever reproach him.”

Yet even as Washington’s will was published hundreds of times in pamphlets and newspapers and the nation learned of its remarkable emancipation provisions, few Americans highlighted it in the way Allen had. In the dozens of biographies of Washington published in the decade after his death, few bothered to mention slavery at all. This silence opened space for future generations to cherry-pick from Washington’s history with slavery as they saw fit.

Indeed, few of today’s comments about Washington and slavery are more vitriolic than the criticisms levied by his nineteenth-century critics. In 1841, for example, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison reminded Americans that Washington was “a slaveholder to the day of his death,” a charge other antislavery activists repeated frequently in both speeches and print.

Likewise, in 1853, radical abolitionist Parker Pillsbury reminded Americans that Washington was “not only a slaveholder, but a slave hunter!!” because of his attempts to recapture Ona Judge, a woman who fled from the President’s House in Philadelphia.

Proslavery white southerners also invoked Washington, insisting they—not abolitionists—were carrying on his legacy. Washington was a slaveholder and had fought a revolution to overthrow British tyranny. Seceding from the United States to establish a slaveholding republic, they argued, was what Washington himself would have done.

They put Washington’s image on the official seal of the Confederacy, and on Confederate money, and at the top of Confederate newspapers. Most notably, when the Confederacy inaugurated its permanent government in Richmond, Va. in 1862, President Jefferson Davis delivered his remarks beneath a towering statue of Washington on George Washington’s birthday, declaring that their cause—the cause of slavery—was “fitly associated” with the day and setting.

These competing claims persisted well after the Civil War. In 1932, as the nation prepared to celebrate Washington’s 200th birthday, the all-white federal planning body worried that, for most Americans, Washington had become “a rather imaginary character.”

Determined to revive the “real” Washington, the George Washington Bicentennial Commission launched a year-long educational campaign. They published books and newspaper columns. They produced teacher training courses, radio broadcasts, and films. They mailed 900,000 posters to American schools. They put Washington on the quarter.

None of this material explored slavery. For all their talk of reviving the “real” Washington, most white Americans still refused to acknowledge one of the central facts of his life and legacy.

Black Americans refused to accept that erasure. Black newspaper editors and activists presented a rival account of who the “real” Washington was, emphasizing his involvement with slavery. The Baltimore Afro-American, one of the nation’s most prominent Black newspapers, ran stories declaring “Washington, on Horseback, Whipped Women Slaves until Blood Ran.” In headlines, they described him as “GEORGE WASHINGTON, SLAVE DRIVER.”

Nearly a century before today’s debates about monuments, the paper argued that statues of Washington should all include explanatory text acknowledging his involvement with slavery.

On Feb. 22, 1932—Washington’s 200th birthday—renowned scholar W. E. B. Du Bois praised Black Americans’ efforts to reveal Washington’s role as an enslaver. In an address in Philadelphia, Du Bois condemned Washington for failing to take a public stand against slavery, accusing him of having “the same ordinary attitude with which modern white men weakly face the issue of race when it is placed before them.”

Americans’ arguments about George Washington and slavery have never been only about him. Rather, Washington has served as a stand-in for the nation itself. His history as both enslaver and emancipator has allowed generations of Americans to selectively cite evidence, wielding the past in service of contemporary debates, rather than trying to understand or reckon with it.

The uncomfortable truth is that Americans have mostly been having the same argument about Washington and slavery for nearly 250 years. Should we condemn him, redeem him, or avoid the question altogether?

Americans have never had one answer, largely because we’ve never agreed on what liberty, justice, democracy, or America itself should mean, either.

Attempting to silence the issue by removing an exhibit in Philadelphia will not resolve these tensions. Each generation must confront Washington’s legacy anew, grappling with its discomfort and ambiguity.

Leave a comment