Beyoncé‘s Cowboy Carter album is dominating the country charts. Yet, it’s also provoked a backlash from those who think the pop star isn’t cowboy enough for the genre. One redditor proclaimed “OMG. She is not country. She just thinks if Taylor [Swift] can switch genres, she can.” Another redditor called her music “ghetto trash.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

And this isn’t the first time that some country artists and fans rejected Beyoncé. When she performed at the 2016 Country Music Awards, chart-topper Alan Jackson walked out and Travis Tritt tweeted, “I love honest to God country music and feel the need to stand up for it at all costs. We don’t need pop or rap artists to validate us.”

At their core, these responses encapsulate a historic belief that certain people get to decide who can be a cowboy and make cowboy music, and who can’t. This gatekeeping evolved alongside the iconic image itself during the Jim Crow era, helping ensure that Americans increasingly defined the cowboy as white, straight, and male. So successful was the equation of the cowboy with whiteness, that well into the 21st century, artists like Beyoncé are not just performing for their audiences but educating them on their right to exist in country-western, cowboy spaces.

Historically, the American West, especially along the southwest border, was a racially diverse, multilingual, and sexually flexible space. Both enslaved and free Black people were central to the cattle industry that was a crucial part of the economy during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

After the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, when the U.S. claimed huge swaths of Mexico as the spoils of victory, an enslaved Black workforce, alongside some of the most powerful horse-based Indigenous tribes, helped adapt Hispanic vaquero culture into mounted North American herding practices. Historians estimate Black drovers, trainers, breeders, and herders—who were collectively referred to as cowboys—made up as much as a quarter of working ranch hands during the heyday of open-range ranching in the second half of the 19th century. In fact, the quintessential cowboy song, “Home on the Range,” was collected by a white musicologist from a Black cook on a Texas cattle trail.

Read More: Fans React to Beyoncé’s New Album Cowboy Carter

Once seen as ruffians and pushed to the outskirts of Victorian society, cowboys were reinvented as rugged cultural heroes in the American consciousness in the early 20th century through dime novels, rodeos, movies, and more. Cowboys became an amalgamation of American rural identity; it didn’t matter if you were an Appalachian coal miner or a logger in the Pacific Northwest, you could be a cowboy.

Cowboys also soon became associated with country music. Between the 1930s and 1950s, the use of cowboy hats and boots crafted the image of a more honky-tonk country artist who replaced the overall-wearing Appalachian “hillbilly” as the genre’s icon. At the same time as white southerners adopted the white cowboy as the symbol of country music, they increasingly shunted aside Black musicians, who previously had participated in the shared working-class genre, forcing them into a separate category: the blues.

Segregation also started to affect the Black Americans who had actively participated in the popularization of “the cowboy” and the crafting of country-western culture, with rodeo and Wild West show performances by famed Black rodeoer Bill Pickett in the early 20th century and movies like Herb Jeffies’s Harlem on the Prairie (1937). Increasingly, they had to perform with care — and in many states, in separate spaces, after officials began enforcing Jim Crow laws in public places, including musical performances, movie showings, and rodeos.

With the entrenchment of segregation laws and the reemergence of the KKK, rodeo producers and local discrimination laws forced Pickett and other Black rodeo stars to pose as Indigenous or Hispanic in places like Texas. And as white cowboys organized unions in the 1930s (eventually becoming the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association), women of all races and men of color were effectively pushed out of the highest earning rodeos around the country. In the mid-20th century, Texas’s highly exploitative prison rodeo—held at the state prison in Huntsville every Sunday in October from 1931 until 1986—was one of the few places an American could watch Black and white men perform as cowboys side-by-side.

Responding to their exclusion from country music and rodeo, Indigenous and Black communities created vibrant rodeo and music circuits of their own that allowed them to perform safely. By the 1940s and ’50s, San Antonio held numerous Black rodeos and local riders participated in the Southwestern Colored Rodeo Association, which organized a circuit of Black rodeos in central Texas, while other Texas communities incorporated Black rodeos into Juneteenth celebrations.

Yet, despite their perseverance, Cold War American popular culture featured two paradigmatic cowboys: John Wayne and Ronald Reagan. Neither had been actual range hands or even hailed from the regional West or South. But the two men — whether they were in films or engaged in politics— embodied a white, hypermasculine, taciturn, and violent ethos that defined Americans’ image of the cowboy, which became ubiquitous in popular culture.

This ideal meant there was little space for Black country artists like Linda Martell, who Beyoncé referenced on Cowboy Carter. Executives, fans, and peers repeatedly told Martell she didn’t belong in the genre in the 1970s. The same went for many Black rodeo stars, who were not just told they didn’t belong but for decades faced intimidation and violence in rural, southern communities. Willie Thomas received death threats from the KKK in the 1950s, and Abe Morris was attacked at a Louisiana bar in the 1980s following a rodeo.

Similarly, there was little room for gay men or lesbians in cowboy culture. Gay rodeo cowboys participated in the surge of popularity around country-western culture in the 1980s and 1990s, as line dancing replaced disco at many bars around the country, mechanical bull riding became a national pastime, and Garth Brooks became synonymous with country music and one of America’s biggest stars. Yet like Black Americans, LGBTQ+ riders were not welcomed on the mainstream rodeo circuit, and they too created their own space: the International Gay Rodeo Association. Even there, they faced community outrage and homophobic slurs.

Despite the violence faced by queer cowboys and Black rodeoers for pushing the boundaries of the country-western world, country music has moved in new sonic and cultural directions over the last 30 years.

But there was a catch: fans and the country music industry have only allowed white artists to tweak the genre’s stylings. Artists like Brooks, as well as Beyoncé-naysayers Jackson and Tritt, were heralded as trailblazers for edging country and pop closer together in the 1990s, breaking with “tradition” themselves. Similarly, country music fans didn’t ask Taylor Swift, who hailed from suburban Pennsylvania, for her cowboy credentials when she entered the genre as a star-spangled pre-teen in the 2000s. Florida Georgia Line even featured the Black rapper Nelly on their song “Cruise,” which spent a record-breaking 24 weeks in 2013 at the top of Billboard’s Hot Country list.

Read More: Beyoncé Is Boldly Defying Country’s Stereotypes

Yet, the country music industry and fans have regularly questioned the credibility of Black artists, continuing the gatekeeping traditions of the 20th century. After just one week on the Hot Country Songs chart in 2019, Billboard removed Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” from the list, arguing it “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.” Even when country music stalwart Billy Ray Cyrus came to the song’s defense, tweeting out, “it’s honest, humble, and has an infectious hook, and a banjo. What the hell more do ya need?” and collaborated on a remix, Billboard refused to back down.

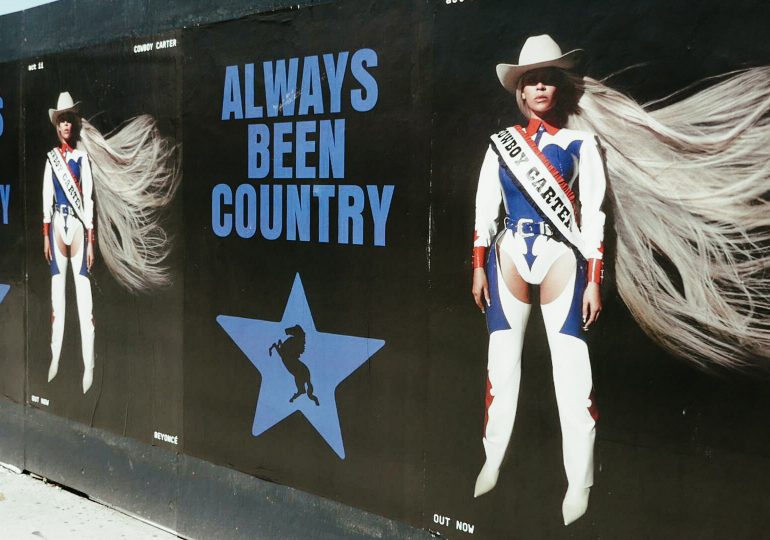

The reaction to Cowboy Carter has reinforced how, at its root, many Americans see the “cowboy” as a stoic, white, straight man. Beyoncé hails from Texas, homeland of North American cowboy culture and country music luminaries like Willie Nelson and George Strait. And yet, everything from her use of rodeo queen imagery (derided as “White Woman Cosplay” by Black rapper Azealia Banks) to her depiction of the American flag on the “Cowboy Carter” album cover has provoked backlash and questions about authenticity.

But this shouldn’t be surprising. It’s the result of more than a century of history in which a large power structure worked to portray white, straight men as the cowboys, enshrining Jim Crow gatekeeping, and erasing a century of rangeland labor and country cultural production by Black Americans. Until that power structure is upended, the same pattern will continue to repeat itself.

Elyssa Ford is associate professor of history at Northwest Missouri State University. She is the author of Rodeo as Refuge, Rodeo as Rebellion: Gender, Race, and Identity in the American Rodeo and Slapping Leather: Queer Cowfolx at the Gay Rodeo. Rebecca Scofield is associate professor of history and Chair of the Department of History at the University Idaho. She is the author of Outriders: Rodeo at the Fringes of the American West and Slapping Leather: Queer Cowfolx at the Gay Rodeo. She is also the PI for the Gay Rodeo Oral History Project.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Leave a comment