The current cease fire in Gaza has given the world hope that the war will end. Yet the extensive destruction suggests that only a massive rebuilding project can make it livable again. Recognizing this, President Donald Trump has offered various proposals for Gaza’s redevelopment. His self-proclaimed “natural instinct as a real estate person” is meant to be evident in these plans. Trump is not, however, the first New York real estate developer to suggest external development and management of the area.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Over a century ago, another New York real estate magnate weighed in on the future of this land. Manhattan developer Henry Morgenthau Sr., whose donations to Woodrow Wilson’s presidential campaign earned him the Ambassadorship to the Ottoman Empire in 1913, helped forge the political tradition of outsiders advocating for some form of external control of the region—a tradition that has bred mistrust among its people and has been disastrous for their interests.

Morgenthau began his tenure as ambassador doing what he expected to do, which was to aid U.S. missionary and business interests in the Ottoman lands. He toured Palestinian lands in April 1914 and, like many American visitors of the era, was captivated by the holy sites but found the region’s poverty off-putting. As World War I commenced, his job became far different. He funneled money to support American-affiliated interests in the region, including Zionist colonists who had lost nearly all forms of income because of the war.

In 1916, Morgenthau resigned in despair, having been able to do little to stop the massacre of Armenians, and returned home to help Wilson’s re-election campaign. He went on a speaking tour of the United States, with numerous organizations feting him for his wartime humanitarianism. In these speeches, Morgenthau discussed his plan for Palestine, declaring that “Jews and Christians should unite in the purchase of this sacred land.” Claiming to have already discussed this with receptive Ottoman leaders, he contended that “once purchased, Palestine should be turned into a small free republic or an international park, in whose government the Christian nations of the world would participate.” Developers would construct a large new harbor in Jaffa and tourists would stream in.

Such a plan focused on development, not diplomacy, and Morgenthau should have known that his comments would make it back to Istanbul. Later that year, Morgenthau’s successor as Ambassador, Abram Elkus, reported that he was struggling to accomplish anything that required Ottoman government permission, and that Morgenthau’s Palestine plan was the culprit. The “real trouble,” Elkus had been told, was that Morgenthau’s assertion that “Turkish officials were willing to sell Palestine or that he could buy it” had been “widely circulated.” The Ottomans “now believe that the United States has designs upon their territory” just as the European imperial powers did. Trust had evaporated.

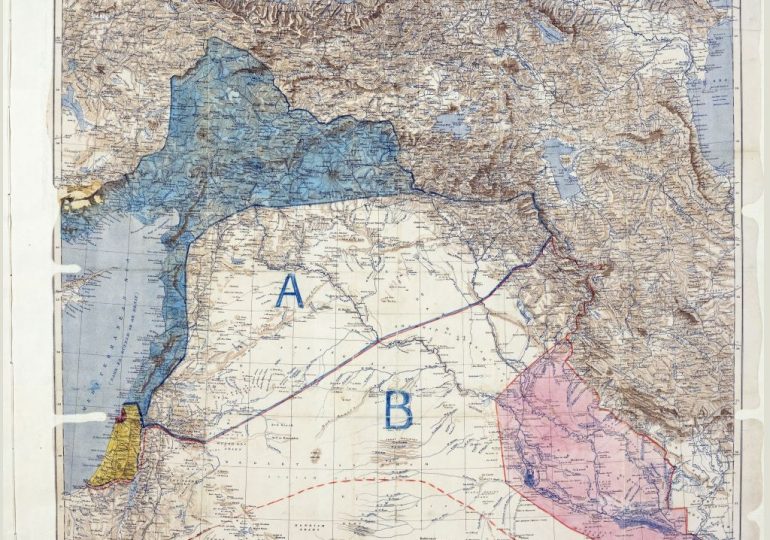

Morgenthau was not the first to suggest something like this, and a similar plan was brewing concurrently. In 1916, the British and French were negotiating the possible post-war fate of the Ottoman lands. In what has come to be called the Sykes-Picot Agreement, they agreed to place Palestine under “an international administration” of some form. They eventually jettisoned this element of the agreement and Britain retained what became known as Mandatory Palestine after the war, championing the immigration of European Jews to the region despite resistance from Palestinians.

Despite being the rulers of Palestine, British officials continued to suggest international control of at least part of the region. Perhaps most prominently, what has come to be known as the Peel Commission visited the region to investigate the 1936 Arab Revolt. One of its recommendations at the time was to form an “enclave” around the “Holy places” (including Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem) to be governed by international “trustees” who would “promote the well-being and development” of the region. The United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 similarly created a “Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem” which extended to Bethlehem. In the end, neither Morgenthau’s plan, nor any of these other proposals, ever gained traction.

And yet the idea of foreign powers or investors believing that they know the best use for the long-contested land has persisted. Months before the recent cease fire, Trump offered to “take over the Gaza Strip,” despite it not being his to control—“and we’ll do a job with it too,” he added. “We’ll own it and … create an economic development that will supply unlimited numbers of jobs and housing for the people of the area.” It would become, he argued, “the riviera of the Middle East” and an “international, unbelievable place.”

The cease fire plan replaced the President’s initial idea with the promise of “a Trump economic development plan.” A “panel of experts who have helped birth some of the thriving modern miracle cities of the Middle East,” referring to the oil-rich cities of the Gulf, would oversee this plan, with “long-term internal security” provided by an “International Stabilization Force.”

Trump has joined Morgenthau and a long line of external actors planning the future of Palestinian land. But for many, Trump’s statement, even as it has been overtaken by the reality of the cease fire, represented a dismaying shift: They heard the leader of a country that enabled Israel’s destruction of Gaza discussing it as a possible real estate bonanza—“the transformation of mass death into a development project,” in the words of historian Taner Akcam—and pictured an intervention well beyond those of his predecessors. While it is not yet known what exactly a Trump-led economic plan would look like, it is already clear that no Dubai-like development could rebuild what the people of Gaza have lost.

Andrew Patrick is a Professor of History at Tennessee State University, a scholar of U.S.-Middle East relations, and the author of the book America’s Forgotten Middle East Initiative: The King-Crane Commission of 1919.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Leave a comment