Since most Americans don’t think much about Lewis and Clark beyond elementary school, it often comes as a surprise to learn that Meriwether Lewis died by suicide in 1809. It was just three years after the end of the cross-country expedition to explore the lands of the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the nation. He was only 35 years old when he passed away, and the historical evidence shows that the cause of death was self-inflicted gunshot wounds.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

America doesn’t like to think of one of its heroes taking his own life. But Lewis’ life and death can help us to recalibrate notions of masculinity as our collective focus turns toward men’s mental health and the “male loneliness epidemic.” It helps us think through cultural notions of masculinity, which place value on men hiding or burying their emotions and which have served as roadblocks to prevent men from receiving the mental health treatment they need.

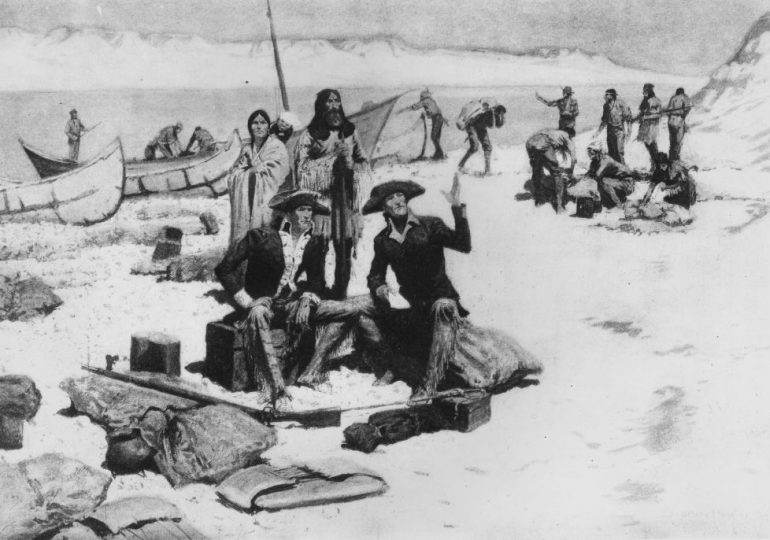

Such harmful ideas surrounding American masculinity have been shaped by the history of male wilderness heroes like Lewis and Clark, who have been portrayed as brawny, self-sufficient, stoic strongmen who know how to navigate any terrain and could survive the frontier.

But there is another side to this wilderness masculinity: the introspective and melancholic one. In fact, Lewis appears to have been highly self-aware, in touch with his emotions, and capable of expressing them. Lewis’s expedition journals and post-expedition letters show him to be a thoughtful, sensitive, and poetic man plagued by anxieties. On his 31st birthday on Aug. 18, 1805, during the first half of the expedition to reach the Pacific Ocean, Lewis wrote of his disappointment at feeling as if he had wasted his life: “I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the happiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation.” He ended the passage by formulating a strong defense mechanism to redirect his thoughts: “I dash from me the gloomy thought and resolved in future … to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself.”

Read More: How To Create a Sense of Belonging In a Divided America

Lewis’s constant worry throughout the expedition—about crossing the Rocky Mountains before winter, acquiring horses, finding guides—raised the possibility that his symptoms of anxiety could actually have been part of what made him well suited as a leader of a cross-country expedition. His tendency to become overly concerned for the future and highly reflective about the past caused him to plan for a myriad of contingencies and to become prepared for the worst. And he did this well. Only one expedition member died, and they succumbed to a disease incurable during the early 19th century.

Following the expedition, Lewis’ life began to unravel once he took on a new position as the governor of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. In this new role, he was unable to do two things he really wanted to do: find a wife, and write and publish his account of the expedition.

Lewis also faced tremendous threats to his finances and career, and he had two failed suicide attempts. He encountered trouble at his job as appointed governor, from which he may have faced removal, and he had mounting personal debts. The federal government questioned his job-related public expenditures and denied payment on them. His creditors then came calling for his private debts once they learned of this denial. Lewis took his final earthly journey to Washington, D.C., to explain himself and collect payment. He feared complete financial ruin.

He was also incredibly lonely. As a tall, handsome national celebrity, one might assume that Lewis would have made an easy match. And yet he died unmarried with no children.

In letters to friends, Lewis made light of it by calling himself a “fusty, musty, rusty old bachelor.” But, in another letter, he also confided that he felt adrift: “Thus floating on the surface of occasion I feel all that restlessness, that inquietude, that certain indescribable something common to old bachelors, which I cannot avoid thinking my dear fellow, proceeds, from that void in our hearts, which might, or ought to be better filled. Whence it comes I know not, but certain it is, that I never felt less like a heroe than at the present moment.” The slow, quiet devastation of making it to the age of 35 without having experienced the love and support of a romantic partner that he needed took a heavy toll on Lewis.

Read More: U.S. Suicide Rates Reached an All-Time High in 2022

Lacking a sufficient support system headed by a life partner, Lewis did not have anyone close enough to help him weather the storms of a life turned very chaotic. William Clark got married upon returning to St. Louis when their famous journey was over. When he learned of Lewis’ death, Clark wrote to his own brother Jonathan in terms that support the supposition that Lewis’s death was indeed a suicide. Clark was afraid that “the waight of his mind has over come him.” He had received an earlier (now lost) letter from Lewis that probably suggested some sort of mental disturbance. Without anyone to stop him, Lewis ultimately shot himself twice at an inn on the Natchez Trace in Tennessee on Oct. 11, 1809.

American culture prides itself on individual independence, with mainstream mental health care advocating for self-care and self-love above nearly all else. Lewis’s fate, and that of other suicide victims, shows how this rhetoric can only take us so far. Lewis desperately sought to break outside of himself, to stop carrying his burdens alone, and to disperse his talents and knowledge out into the world, in writing, to a lover, to his own family. But these opportunities never came. Loneliness on top of pre-existing mental illness can be immensely devastating, and for Lewis, it was deadly.

For centuries suicide has been associated with cowardice and shame. Lewis’ death shows that even those whom America reveres as the bravest of men struggle with mental illness. In his final moments, Lewis tried to immortalize his own strength in fighting an inner battle alone. One of the last things he said before he finally transpired was “I am no coward; but I am so strong, so hard to die.” It is only fair to treat Lewis—and other men who suffer as he did—as he last wanted to be remembered: as a strong and courageous person fighting mental illness without sufficient support.

Jamie M. Bolker is a former National Endowment for the Humanities fellow and scholar of early American literature and culture. She is writing a book on what it meant to get lost in America centuries before the invention of GPS. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental-health crisis or contemplating suicide, call or text 988. In emergencies, call 911, or seek care from a local hospital or mental health provider.

Leave a comment