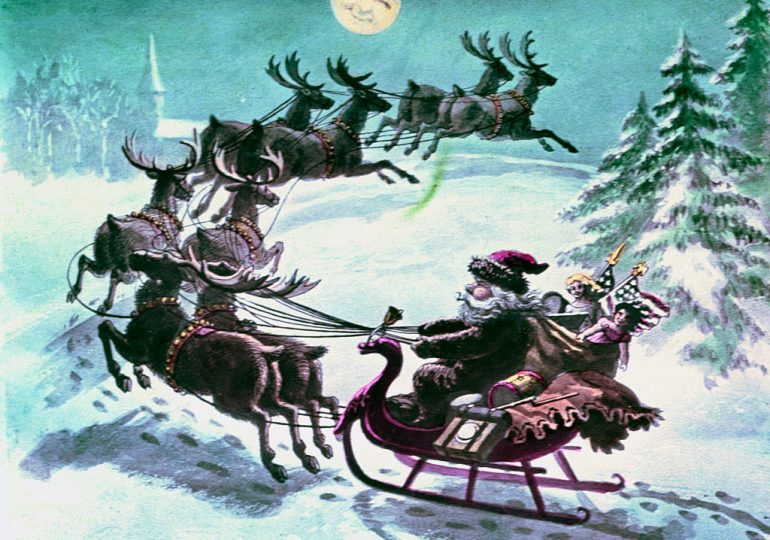

Just prior to Christmas in 1823, a poem called “A Visit from St. Nicholas” appeared in the Troy Sentinel, sans attribution. The author, perhaps viewing this particular literary excursion as slumming it, was Clement Clarke Moore, who had hit upon the idea of a Christmas poem for the American masses the year prior when out riding in a sleigh.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

A respected academic, Moore regarded such verse below his intellectual station, and yet, he couldn’t help himself. The result: the one poem with which almost all Americans have some familiarity—and something rather better than that, too.

The poem is narrated by a man who gets out of bed and observes none other than Santa Claus himself coming down the chimney, putting out the presents, and even giving a signal before exiting back up the chimney with a touch of his nose. As I’m sure is the case for many, both the very idea of Christmas and the words of Moore’s poem—which is often erroneously billed as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”—seemed to enter my consciousness at the same time. What most struck me about the latter is also what impacts me the most about it all this time later.

We all reach a point when it’s made official to us that Santa is not real. But this makes me uneasy, and I refuse to vouchsafe that he isn’t.

What is Santa meant to be? Wish-granter? Present-bearer? If that’s what we think, Santa is a bit like Amazon, but with a sleigh and bells rather than one of those huge vans that make a swooshing sound when backing up.

Read more: The True History of St. Nicholas Is a Christmas Mystery

Clement Moore wasn’t the best guy. He was an anti-abolitionist for starters, which is well beyond “naughty.” But he made Santa real in a way that went beyond the physical, beyond gifts. What the narrator of the poem is rendered agog by is wonder. Mystery. Faith.

You know how people say, “That’s my president!” I say, “That’s my Santa.” He is a force of the imagination, of thinking of what we might do to make someone else happy, to show them that we care.

When I was a kid, I had this Pez dispenser that was purple with a skeleton head. I liked scary things. One day I lost it outside at a neighbor’s house. It started pouring. I came home and told my mom. She knew I was upset, so she got out the raincoats and we went back across the street and she helped me find it.

When I think about my mother and love, I think about that memory. I’m calling to mind a rainy September day, but that was a Santa-esque moment too. She cared, so she accepted that this silly object meant something to me and my imagination.

When we cease to believe in that which we cannot touch or see, we are not as human as we might be. We’re diminished. The Santa of Moore’s poem transcends the space of one’s chimney and one’s childhood.

I’ve repeatedly been told that this is likely the last year that my 10-year-old nephew will “believe.” We say it that way, right? As if the concept of belief itself has come to a close.

I didn’t believe for a while. Ironically, as life got harder and lonelier, I began to believe again, in a manner beyond the scope of making a list and putting it in the mailbox with extra postage for the North Pole.

Is a theme not real because it doesn’t have a first and last name? Is selflessness not real because it’s rare? Is the love you had for someone not real because they’re gone?

Read more: After My Parents Died, I Lost the Christmas Spirit. Now It’s Slowly Coming Back

Santa Claus is a spirit of hope. We’re often not very good to each other, are we? The narrator of Moore’s poem experienced, as if by a vision, a potent reminder that he could be good to people, and selfless.

The poem is less about what he sees than what he believes. And belief always starts with what we allow ourselves to be open to.

I will always be open to the realness of Santa Claus. Sometimes I read this poem to confirm what I already know, and other times I merely look within myself to find Santa Claus and all he represents.

He couldn’t be more real to me than if I looked up into the sky and there he was. May he be so for you, too.

Leave a comment