Covid has been running amok in the Chinese capital. What happens there will reverberate around the world.

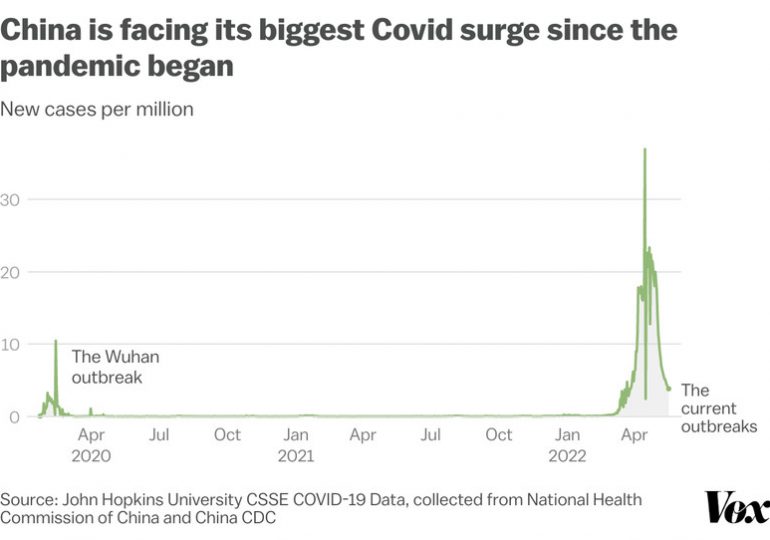

After successfully curbing the novel coronavirus for most of the past two years, China in recent months has faced its biggest Covid-19 surge since the virus was first discovered in Wuhan in December 2019. The Covid wave caused by the highly contagious omicron variant has spread across many major cities, including Shanghai.

This past month, the wave has reached the capital, Beijing, and what happens there could have enormous implications for the course of the pandemic, China’s government, and the global economy.

As of Wednesday, May 18, Beijing has reported 719 cases since the beginning of the month, part of the worst surge the city has faced since the virus emerged. By comparison, Shanghai, China’s economic capital, which had previously dominated the headlines for its devastating surge, has reported 4,798 cases since the beginning of this month. China as a whole has passed the 1.5 million Covid-19 total confirmed case count, with the vast majority of cases reported since the beginning of March.

Although the Beijing case count is lower compared to Shanghai’s, and considerably lower than what’s been seen in the United States, China has responded with urgency. Beijing officials have rolled out numerous policies from their zero-Covid pandemic playbook. This has included rounds of mandatory mass PCR testing for its population of 22 million residents; partial lockdowns; contact tracing; isolation of cases and close contacts; sealing off of buildings; public transit cutbacks; closures of schools, malls, movie theaters, and gyms; and bans on indoor dining at restaurants.

Zhuoran Li, a research assistant at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, told me, “Family and friends in Beijing have told me that, right now, it’s still more of locking down [specific] communities rather than the entire city. My uncle and aunt, [for example], can still go buy food themselves.”

Chinese authorities are acting quickly to prevent Beijing from entering a full-scale lockdown, which was undertaken most notably and recently in the financial capital, Shanghai. The lockdown there, which involved quarantining a city of over 26 million people, has come under much criticism — both domestic and international — with stories coming out about food shortages and civilians’ inability to access basic medical care.

Even as global Covid-19 cases passed the 500 million mark this month, many countries around the world, notably the United States and those in Europe, have relaxed their pandemic protection policies, choosing to live with the virus. China, meanwhile, has held steadfastly to its zero-Covid plan — an approach it once shared with countries like Vietnam and New Zealand but is now alone in pursuing.

Many experts and pundits, particularly in the West, have characterized China’s zero-Covid pandemic policies as draconian and ineffective in the face of the extremely contagious omicron variant. Increasingly, some members of the Chinese public and intelligentsia are also expressing mixed feelings on the policy. But the Chinese government remains unbowed; an editorial in the state-owned Global Times touts the policy for adhering “to the principle of people first and life first,” in contrast to the “cruel social Darwinism” of the West.

What’s playing out is a major test for the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), whose leader, President Xi Jinping, has elevated the country’s pandemic response to shore up the party’s legitimacy. China is gearing up for the 20th Party Congress, the country’s paramount political event, where the party decides China’s leadership every five years and sets key policy priorities. This year, Xi is widely expected to secure an unprecedented third term in power.

For the wider world, China’s Covid troubles could exacerbate global supply chain issues, food shortages, and inflation, as well as increase the risk of a global recession. Like China’s initial battle with Covid, the country’s latest struggle will determine the fate of more than just its own population.

Just how bad is the latest Covid outbreak?

While questions have been raised about the accuracy of Covid-19 data reported by the Chinese government, there is no doubt that the current outbreak in Beijing is the worst the city has seen since the beginning of the pandemic. Aside from an outbreak in the summer of 2020, the capital had mostly been spared from Covid-19 over the past years. As a result, Beijingers had been able to live life with relatively few restrictions, and the city held major events like the centenary of the CCP and the 2022 Beijing Olympics without any subsequent outbreaks.

John Hopkins University CSSE

All this has changed with the arrival of the more contagious omicron variant, which China has had difficulty bringing under control with its zero-Covid approach. Not only is omicron more contagious, but it is also much better at evading the defenses of people who have been vaccinated. In the country more broadly, there were lockdowns of some sort in more than 40 cities as of May 5, affecting up about 327.9 million people, according to a CNBC report.

Though a staggering number, the population affected by lockdowns is not even close to a majority of China’s overall population. Benjamin Cowling, a professor and epidemiologist at the University of Hong Kong, told me, “Most of China is normal — no masks, no social distancing, very limited impact on daily life — and that doesn’t come across in the coverage of Covid in China. It looks like China is having chaos, but it’s [mainly cities like] Shanghai having these measures in place.”

However, China’s current struggles with containing Covid and the scale of the current outbreak do reveal a major hole in the middle of the country’s pandemic strategy: vaccination. Though China’s overall vaccination rate (two doses without boosters) stands at about 87 percent, only about half of people over the age of 80 have been fully vaccinated. That’s because China did not prioritize the elderly for vaccination, unlike many other countries. (Indeed, adults over 60 were not even approved to get the vaccines at first due to initial concerns about side effects from domestically made vaccines.)

Cowling, who recently co-authored a study on vaccine hesitancy among older Chinese adults, told me that the lack of urgency is related to the country’s overall early success in curbing Covid.

“The big fundamental issue is about the risk-benefit calculation for vaccines. Where we always say in the West, the vaccines have small risks, but the benefits far outweigh the risks, in China, you have the risk of the vaccine, which we accept is very, very low, but not zero, but if the government continues with the [zero-Covid] policy and it works, then the benefit is very limited,” he said.

Cowling said that China could have marshaled better messaging on vaccines, like how the UK responded to concerns about the Astra-Zeneca vaccine causing blood clots. Ultimately, the majority of those who have died in cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong have thus far been the unvaccinated elderly.

Along with low vaccine uptake, the Chinese-made vaccines are now understood to be less efficacious against omicron than the mRNA vaccines (though about as effective as mRNA vaccines against serious illness and death, with three doses). The disappointing performance of the domestic vaccines has led to questions about why China has not imported the more effective mRNA ones. Li, the Johns Hopkins researcher, described this to me as a form of “vaccine nationalism,” where the Chinese government is trying to be self-reliant and shore up its own biotech and pharmaceutical industry.

“For China, [to import the Western mRNA vaccines] means that they cannot claim this victory anymore, and that they’re conceding their own governance model is not working as well as the American model,” Li said.

Why is it a big deal if the government imposes a Shanghai-style lockdown in Beijing?

Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images

Officials in Beijing have acted fast not to repeat the blunders of their counterparts in Shanghai, where frustration over the government’s handling of the current surge has gone viral across Chinese social media and manifested in often-unseen protests. No tool has been left off the table, including blocking rideshare apps from operating within districts that have been put under lockdown. While authorities have thus far avoided the panic and chaos of Shanghai, this hasn’t entirely stopped dissent from manifesting, including at one of the nation’s top schools, and Beijing’s current battle from Covid is far from over.

There would be deep ramifications if Beijing has to undergo a citywide, Shanghai-style lockdown — for the government, the people, and the world.

A lockdown in Beijing would be seen as a major political loss for the ruling CCP, which, despite the government’s troubled handling of the initial outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan, has been able to successfully manage the pandemic since then.

Xi Jinping in particular has used China’s Covid success to champion the Chinese model of governance, proudly declaring back in October 2020, “The pandemic once again proves the superiority of the socialist system with Chinese characteristics.” In an era where governments increasingly frame events in terms of geopolitical competition between democracies and autocracies, failure in Beijing would be a loss of face.

Jane Duckett, a professor specializing in Chinese politics and society at the University of Glasgow, told me, “I think the government is caught between a rock and a hard place … if it doesn’t try to [contain] Covid, then it will spread, and if we end up with a [situation] like Hong Kong, then their entire, ‘We are going to save lives and our system is superior’ kind of line [falls short] … and [China has] ended up perhaps as bad as some of the countries that the [Chinese] leadership has been very critical of.”

The ones who are most affected and will continue to be the most affected by the Chinese government’s pandemic policies are, of course, the average Zhous, regular Chinese people. Alongside the severe mental health toll that comes with life under lockdown, Human Rights Watch found that there was a “systematic denial of medical needs of people with serious but non-Covid related illnesses,” sometimes even leading to unnecessary deaths.

The economic impacts are also quite severe, as hundreds of thousands of small businesses have closed, while the Chinese stock market has slumped. Unemployment is rising, particularly among young people, with the jobless rate for 16-24 year olds at 16 percent (nationally, it is around 5 percent), and less than half of college graduates this year having received job offers.

Chinese officials are aware of all this, and have taken some action to ameliorate the economic downturn. This includes provisional living allowances for unemployed migrant workers, who already deal with a great deal of precarity in normal times, as well as infrastructure spending to shore up the economy. All of this may not be enough, though; as Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, put it in an interview, “The stimulus measures are like a band-aid for an amputation.”

Economic issues in China, the world’s second-largest economy by GDP and the largest exporter of goods, have already begun to reverberate around the world.

For one thing, China’s lockdowns are further roiling a global supply chain already backed up by previous shocks during the pandemic, which will lead to longer delays for goods like electric vehicles and iPhones.

This goes beyond consumer goods, though, as China is also the world’s second-largest exporter of fertilizer after Russia, and the country has increasingly curbed much of its fertilizer exports since last summer to prevent domestic food security issues. Because Russia did the same in the wake of its war on Ukraine, these twin crises are likely to exacerbate an alarming food crisis, potentially deepening hunger in places like Africa and West Asia.

And any downturn in China’s stock market and economy will in turn adversely affect the economies of countries in the Global South that have particularly close economic ties, like South Africa and Brazil. This could all possibly dampen the overall global economy, and perhaps even intensify the risk of a global recession.

If there’s one thing we have learned from this pandemic, it’s that what happens in China doesn’t stay there; it has deep implications for the rest of the world. The course of Beijing’s fight against Covid may well have consequential repercussions beyond China’s borders.

Leave a comment