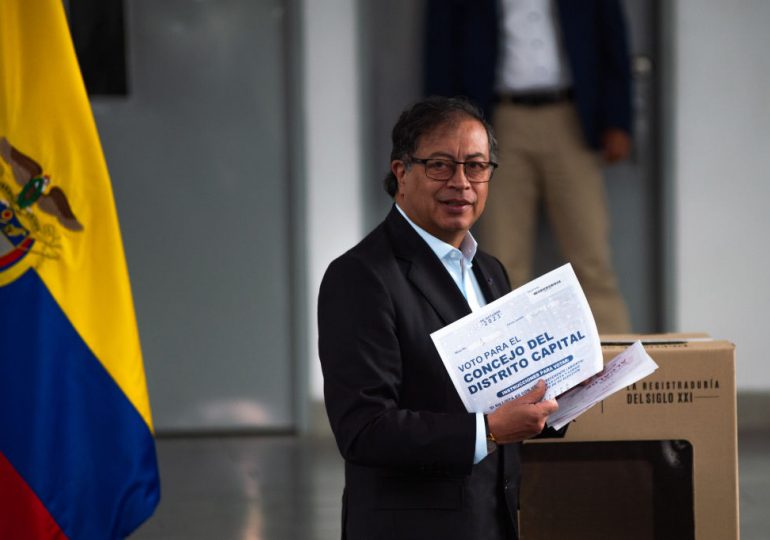

The location for my Dec. 3 interview with Colombian President Gustavo Petro is arranged with all the formalities of a bilateral meeting between heads of government. Staff have arranged his seat on the patio of a luxury beachside hotel in Dubai to carefully avoid the sun and placed a Colombian flag on the nearby table. Men with earpieces linger in the background.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But from the moment he walks in, Petro dispatches with the decorum. He’s dressed in a crisp white shirt, jeans, and loafers—no tie, no jacket. And he has no patience for the diplomatic talking points that officials typically deliver from such a post. Climate change is a matter of “life and death,” he says, and the time has come for countries to move past their narrow self interest and antiquated market-based policies. “The presidents come to make some prefabricated speeches that they themselves do not write, generally, that introduce what I would call a ‘correct’ policy,” he says. “That ‘correct’ policy is false.”

The correct policy, in Petro’s view, is to ditch fossil fuels. And he is positioning Colombia not only as a key advocate for the global energy transition but also as a test case of how a fossil-fuel-producing country can decarbonize. “What I’m proposing is not jumping into a void, as some denialist voices say,” he says. “Rather, it’s a change in the way forward. A way forward which, from my point of view, can be much more powerful, and prosperous, than the path that we would be leaving behind.”

As fossil-fuel interests, at both the corporate and national levels, continue to resist the transition to clean energy, Petro could offer a powerful rebuke, showing how an economy can transform and prosper. Now, he just has to deliver.

Climate change is nothing new for Petro, who has worked on the issue for decades and made it a key plank of his presidential campaign last year. In his year and a half in office, he has blocked new oil-and-gas drilling and begun a campaign to ground the economy to its “biological wealth” rather than its fossil-fuel wealth.

His international advocacy on the issue comes at an important moment. Fossil fuels have been at the center of the global climate agenda at COP28, the United Nations climate conference now in its final hours in Dubai, and those conversations have rankled some of the biggest fossil-fuel producers whose economies depend on revenue from the industry.

Colombia offers an important counter narrative. Even though it is the world’s fifth-largest exporter of coal and an oil-and-gas producer with significant untapped reserves, Colombian negotiators have pushed for aggressive language on fossil fuels, making them a leading voice in the fraught talks. And, while in town, Petro himself endorsed a call for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, a proposal thus far shepherded by civil society and small island states, that would provide a concrete pathway for countries to wind down fossil fuels. He is the first leader of a large country and the first of a fossil fuel-producing nation to do so. “For about 40 years now, we have been living from exporting that coal and that oil,” he says. “Yet I’ve wanted to say, first to Colombian society, and now to the world, that even under these circumstances the economy should transition to decarbonization.”

Without listening closely, this can all seem a bit radical. Petro, a former guerrilla movement member turned left-wing economist, spooked the markets when he was elected president last year. And in our conversation he remains true to his roots, citing Marx and delivering a critique of the prevailing economic literature on how to address climate change. Market-based approaches, like a carbon tax, are “sort of like the religious expecting the miracle,” he says. And he says that wealth from carbon-intensive commodities is concentrated among the wealthy, posing a political barrier to climate policy. “Human life can be saved if the total wealth held by the richest 1% falls. And that won’t happen through market mechanisms,” he says.

But his proposals aren’t totally divorced from the conventional wisdom. Indeed, he has found ways to square the market-based order with his socialist roots. Among other ideas, Petro has proposed using the multilateral financial institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to reduce the debt of low- and middle-income countries in exchange for protecting nature and, in turn, slowing climate change. “Capitalism has the financial system as a central node, which in a certain way is for planning,” he says. “And one must appeal to it to emerge from the crisis.” Applications of such an approach, like these debt-for-nature swaps, have significant buy-in across the globe, though the devil is in the details about how to structure them.

As for what he plans to do at home, Petro’s climate program sounds a bit like the other spending programs that have swept the globe, including Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. At COP28, he announced $32 billion in projects to advance green transportation, clean energy, and climate adaptation, among other things.

In many ways, Petro is a unique figure. Despite his populist agenda, he speaks more like a philosopher-economist than a firebrand. He manages good relations with other leaders and policymakers who do not share his ideologies. And his climate advocacy stands apart from many of his left-wing counterparts in Latin America who take an old-school approach and see fossil fuel-created wealth as a necessary source of finance for social services.

Petro tries to look forward. He expresses concern about “barbarism” that might be triggered by climate change and the resulting migration. And he fears the possibility of right-wing backlash from related political disruptions. “There is this rational path forward,” he says. “It’s a question of tapping into the scenarios of human rationality that exist today, under, undoubtedly, dominant political influences, and trying, with planning and quickly, to make the transition to another way of producing.”

But as much as Petro is an outlier, his approach to climate may be a harbinger of what’s to come. At CO28, we can already see this change happening. After close to three decades of negotiators ignoring fossil fuels in their climate agreements, a global consensus to phase them out is now in play. Petro is just one part of that shift, but, as climate change and the havoc it wreaks become more urgent, it is bound to create a new generation of leaders who think about the issue differently.

Leave a comment