Around the world, workers are mobilizing for higher wages while citizens are questioning the very functioning of democratic institutions. In the United States, workers across various industries from film to car manufacturers to coffee shops are demanding adequate compensation.

In Nigeria, similar demands are being made. Meanwhile, just as in the U.S., there is rising distrust in electoral practices. With ordinary people in Nigeria facing significant hardship partly because of the government’s removal of a critical oil subsidy, the country’s largest unions called for and went on a short national strike in November.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

These events, coinciding with the 63rd anniversary of Nigeria’s independence, highlight ongoing questions about Nigeria’s political landscape that reach back to the colonial period and demonstrate the connections between democracy and labor activism.

Read More: Why Nigeria’s Election Is a Key Test for Democracy in 2023

In particular, the relatively unsung ideas of Olaniwun Adunni Oluwole are worth revisiting. She placed the political and economic needs of everyday Nigerians at the forefront of her agenda. Remembering her activism is important not only for rethinking Nigeria’s political future but also for illustrating how solidarity—forged across class and gender lines—can spur change in many contexts.

Oluwole grew up amid the British forces’ gradual subjugation of the communities that were amalgamated later into the colony named Nigeria. Born in 1905, Oluwole attended primary school in Lagos and then worked as an actress and itinerant preacher. Her transition from the pulpit to the political arena occurred in 1945 during one of the most significant moments in Nigeria’s history: the colony’s first and longest labor strike, which involved 40,000 workers and lasted for six weeks.

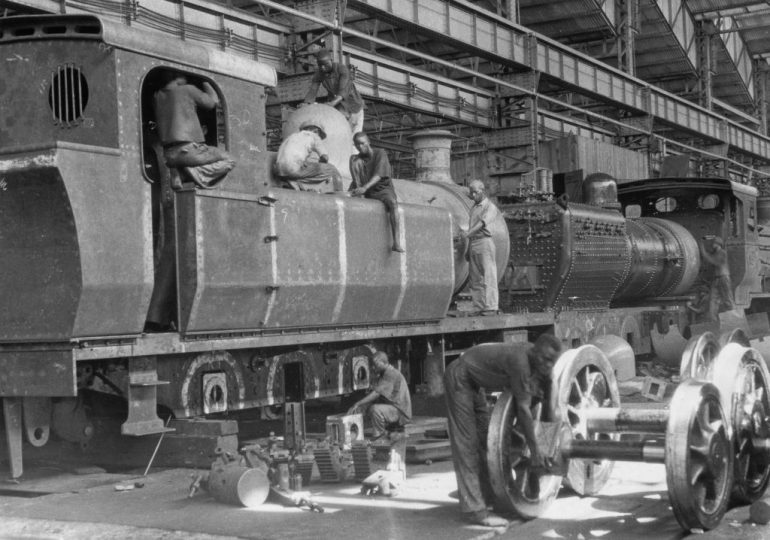

Since 1941, Nigerian trade unions had agitated for higher wages in response to degraded working conditions and economic inflation exacerbated by the Second World War. Shortly after the war’s outbreak in 1939, the British government had diverted food supplies to the army and mandated overtime hours in railway and factory work. Policies pushing farmers to cultivate cash crops at the expense of food crops limited Nigerians’ food production, as did price regulations. These initiatives inflated the cost of basic necessities and made life difficult for colonized people.

These policies also brought Nigerian women into the fight. The Lagos Market Women Association (LMWA), which represented female traders, rejected the wartime price controls, including the government’s decision to buy and sell food at its own stores. Led by the association’s president, Madam Alimotu Pelewura, LWMA members argued that the British government undercut their profits and disrupted the local marketing system. The traders protested price restrictions by storming official meetings, petitioning British officials, and holding street demonstrations. Recognizing the women’s political influence, labor leader Michael Imoudu requested the LMWA’s support in case of a strike, telling Pelewura in a 1941 letter that “our strike is also your own strike.” The labor unions and the broader community shared in the goal of defeating British economic oppression.

Read More: Nigeria Is Bracing for a Potentially Mammoth Strike Over a Hike in the Fuel Price

The over-worked and underpaid unions pressed their employers for cost-of-living salary increases. Although the British governor initially claimed that the government had no funds for African workers, by May 1942, his administration provided “separation allowance” to European expatriates whose wives resided abroad. Finally, in June 1945, the railway workers in Lagos kickstarted the strike that spread across Nigeria. The strikers demanded that the British colonizers increase wages and offer benefits like “family allowances” similar to the European separation allowances for African workers.

Nigerian women sustained the strike by donating funds to the Workers’ Relief Fund. Oluwole, the actress and preacher, devoted herself to the workers’ cause. In addition to feeding workers who visited her Lagos home, Oluwole spoke at strikers’ meetings, encouraging them to maintain the picket line. Her efforts later earned her the title of the “workers’ mother.”

The labor unions also depended on the connections that leaders had forged with the LMWA. The traders aligned with the strikers because of their shared criticisms of the British government’s price controls as well as family ties. Male wage earners were the fathers, brothers, and sons of working women. Traders across Nigeria followed their Lagos peers by selling items to the strikers on credit or reduced prices.

The strike slowed the British government’s emergency war production and forced it to recognize the power of working class people. By December 1945, the British administration agreed to pay workers a living allowance 50% higher than in the pre-strike era. LWMA’s agitations also forced the European administrators to remove gari, a staple food made from cassava, from the control list after the end of war.

The strike’s success demonstrated the transformative power of class and gender solidarity in pressing for workers’ rights and temporarily crippling the colonial economy.

The strike also strengthened Oluwole’s resolve to agitate for Nigeria’s freedom from British rule. Oluwole was convinced that only expelling British colonizers would relieve workers’ suffering and improve Nigerians’ living conditions. She turned her full attention to supporting the Nigerian political parties who were committed to self-rule.

Read More: Queen Elizabeth II’s Death Is a Chance to Examine the Present-Day Effects of Britain’s Colonial Past

The country’s leading politicians had been pushing the British government to accelerate the date for independence to 1956, as well as replace the existing government with a federalist one that would divide power among the three regional legislatures.

However, Oluwole opposed the parties’ agenda, explaining her stance in a 1954 newspaper op-ed: “I am not anti-self-government when it is to the benefit of the majority of the people. The stand of my party is that self-government for Nigeria in 1956 is premature.” She established the Nigerian Commoners’ Party (NCP) to promote everyday people’s interests. It also opposed some Nigerian parties’ agitation for self-government by 1956, concerned that such an acceleration would set up the new nation for failure.

Oluwole’s discontent was shaped by the nepotism, electoral fraud, and aggrandization of wealth that were already unfolding among these parties. Advancing an alternative vision, Oluwole wanted a decentralized and unitary government that would prevent regional power plays and imbalances. She advocated a political structure where local councils with greater administrative powers would coexist with a single legislature.

Before she could do more to achieve her vision, though, Oluwole died at age 52 in 1957.

But revisiting her alternative proposals yields new insights. Her criticisms of Nigeria’s emerging political structure proved prescient. Moreover, lifting up the example of forgotten women like Oluwole today reminds us of the possibilities of “anti-colonial world-making” that exposed the unequal relationship between colonized people and European rulers.

Women’s organizing changed the workers’ conditions and weakened colonial economic order: the 1945 labor dispute’s success depended on the strikers’ connections with women leaders and recognizing their shared struggles against colonial exploitation. By foregrounding the working class’ interests, Nigerian women created and envisioned transformative political changes. Any future for Nigeria will have to do the same.

Halimat Somotan is a historian of 20th century Lagos, Nigeria and assistant professor of African studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

Leave a comment