Five years ago, my dad would have turned 100. The Leonard Bernstein Centennial was a pretty big deal—but I didn’t really grasp the scope of my father’s impact until I started traveling around the country giving talks about my memoir, Famous Father Girl, which came out that same year. Everywhere I went, I met scores of older people who had been there: at Carnegie Hall, at Tanglewood, at the Kennedy Center, and beyond. They’d bought the records; they knew his Broadway shows. The Lenny fan base lives!

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

And they’d watched him on TV. Through his iconic Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein turned more people onto symphonic music than possibly any other person in history. He created lifelong musicians, too. I met so many orchestra members who told me the same story: “I watched your dad’s TV programs when I was a kid, and that’s why I play the viola/French horn/bassoon today.”

They would hold their hand over their heart as they spoke.

Over the past months, my brother, sister, and I have attended many screenings of Bradley Cooper’s film Maestro. In the receptions afterward, we repeatedly encountered this very same gesture: people coming up to us, hand over heart—to share the enormous emotions they had experienced while watching the film.

Bradley Cooper took an enormous risk in showing a very public persona, Bernstein, in the context of his private life. He welcomes his viewers into a liminal space where the daily intensities and negotiations of a marriage are laid bare for all to see. It’s an unusual marriage, yes—and yet, it contains the elements of every marriage. That’s why viewers react the way they do; the specifics have been rendered somehow universal. Not every married couple has a Thanksgiving Day fight as a giant Snoopy balloon floats past the window—but every married person (and child of parents) recognizes that fight.

In the process of his deep, deep dive into all things Bernstein, Bradley read my book. Once he’d decided to steer his story toward the marriage of Lenny and Felicia, he returned to my pages as part of his search for authenticity. Some of the book’s details ended up in the film.

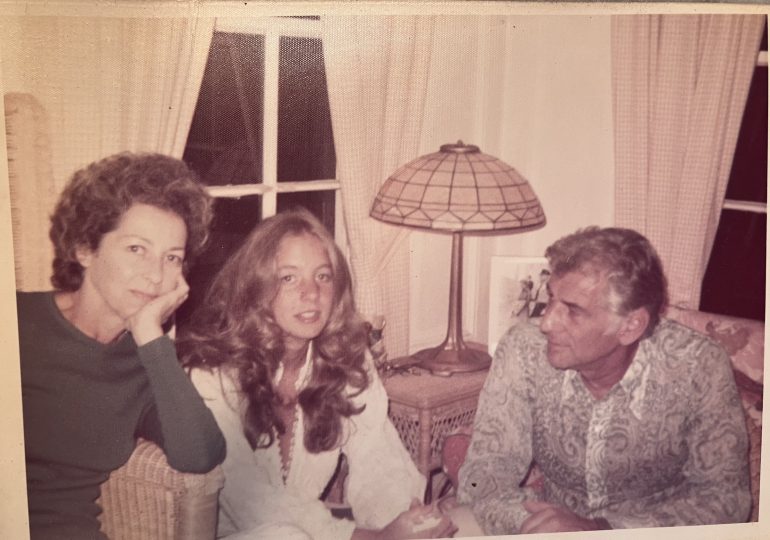

In one chapter, I described spending a teenage summer working at Tanglewood, where I heard stories about my father’s “wild youth,” which included dalliances with men. I wrote uneasily to my mother, mentioning the stories. She evidently shared the letter with my father, who took me aside one evening after dinner to talk about what I’d heard. He said the stories weren’t true. As I wrote about this incident, I included a new thought: it was occurring to me for the first time that my mother might well have put my father up to denying those rumors. Bradley took that piece of speculation and wove it into his narrative. In a perfect example of how storytelling can amplify reality, the scene where Felicia asks Lenny to lie to Jamie, who is played in the movie by Maya Hawke, feels absolutely, painfully plausible to me. And in the next scene, where Lenny and Jamie have their conversation, the long, nearly unbearable pauses convey the inarticulate connection of father and daughter far better than any dialogue could do.

Another crucial section of my book made its way into Maestro—from the chapter where I describe my mother’s final days as she was dying from cancer. This was a very tough time to write about, and my memories were buried deep. Fortunately, I had kept a journal. Forty years later, I found myself reading about the night I sat at my mother’s bedside, having what turned out to be our last real conversation. My mother held my hand and said: “Remember: the most important thing is kindness. Kindness, kindness, kindness.”

It all came flooding back: the sheer drama of the moment. My actress mother was theatrical to the end! (Could she have imagined that one day, a brilliant actress would play this scene to devastating effect in a film about her marriage?) But it took many more years for me to comprehend what my mother was telling me: Don’t let your own feelings prevent you from understanding the feelings of others. Open your heart, and keep your heart open, always.

What an extraordinary message to receive from one’s mother on her deathbed. Have I made good on her advice? I admit I’ve fallen down on the job plenty of times. But I treasure her gift—this triple-strength moral compass, handed to me at age 24.

Hearing the extraordinary Carey Mulligan say those words in the film allowed me to experience their power in a whole new way. Here was a woman who had known fury, regret, and love—and now, at the end, she was choosing love over all other emotions. Clearly, Bradley Cooper understood the magnitude of Felicia’s words—and he uses them to tell us that Felicia is forgiving Lenny: that she is loving him to her last breath, seeing his own true heart in all its anguish and complexity. And we see it too—or rather we hear it, thanks to Bernstein’s music, which drenches the film in his essence.

As Bradley worked on this enormous project, my brother, sister, and I gradually realized how much like our father he actually was. We recognized that intensity, that hyper-focus and perfectionism—but what resonated for us, more than anything, was the all-embracing warmth Bradley brought into every space, and to every person. That was the Lenny-est thing about him. Bradley’s hand was right over his own heart, throughout the making of Maestro. Nothing could have moved us more.

Leave a comment