Government borrowing soared in October as the UK continued to support the economy during the pandemic.

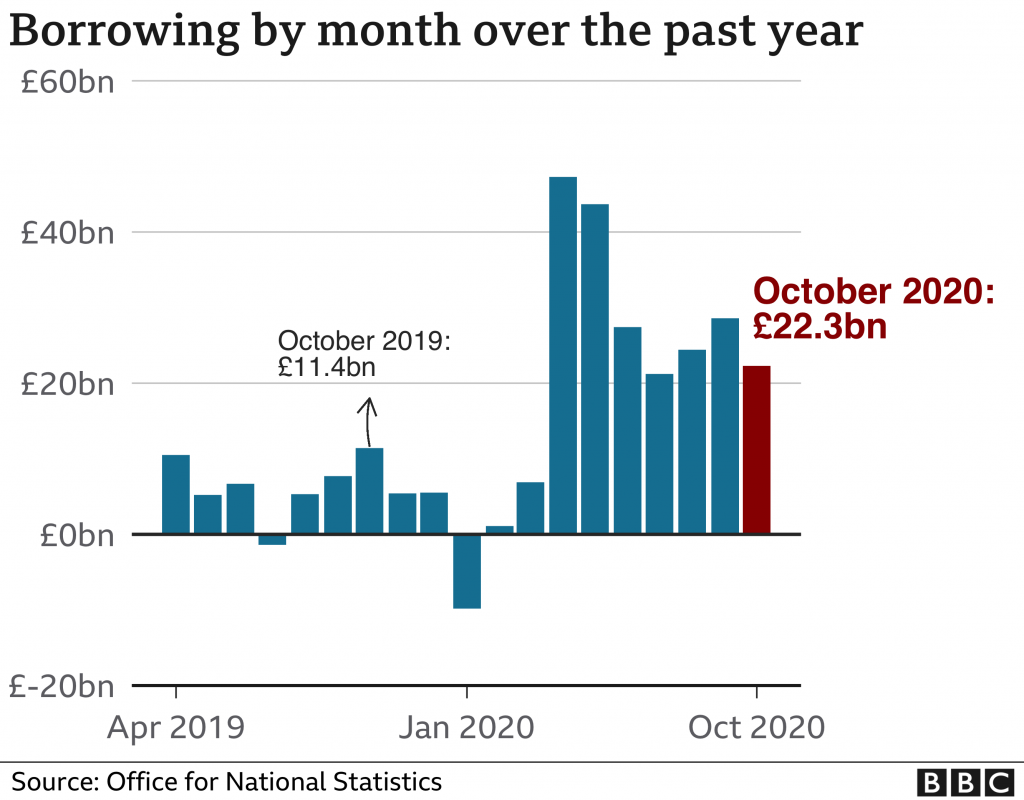

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said borrowing hit £22.3bn last month, the highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

It underlines that the pandemic is having a “substantial effect” on the public finances, the ONS said.

But the figure – the difference between spending and tax income – was not as high as some economists had forecast.

Since the beginning of the financial year in April, government borrowing has reached £214.9bn, £169.1bn more than a year ago.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has estimated it could reach £372.2bn by the end of the financial year in March.

Where does the government borrow?

The government borrows in the financial markets, by selling bonds.

A bond is a promise to make payments to whoever holds it on certain dates. There is a large payment on the final date – in effect, the repayment.

The buyers of these bonds, or “gilts”, are mainly financial institutions, like pension funds, investment funds, banks and insurance companies. Private savers also buy some.

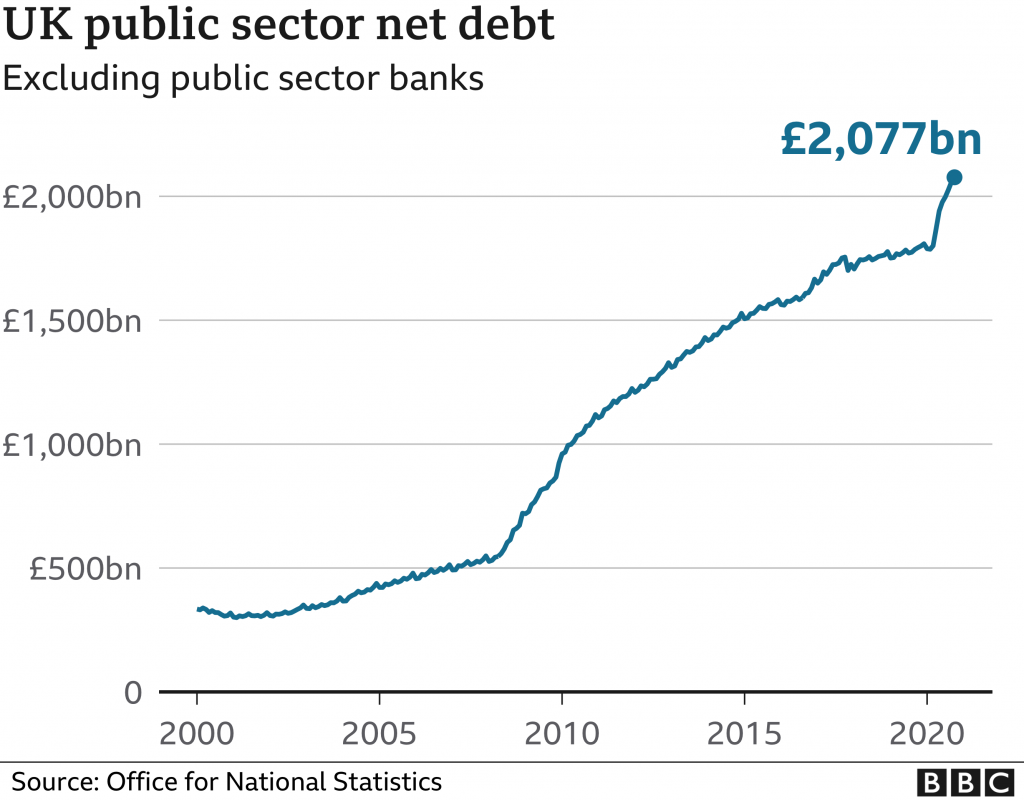

The increase in borrowing has led to sharp increase in the national debt, which now stands at £2.08 trillion, larger than the size of the economy.

The UK’s overall debt has now reached 100.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) – a level not seen since the early 1960s.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) will publish its latest forecast next week, when Chancellor Rishi Sunak, announces his Spending Review.

Millions of public sector workers face a pay freeze as part of that review, as the chancellor makes the case for pay restraint to reflect a fall in private sector earnings this year.

The Treasury is trying to bolster public finances after the huge rise in spending to fight coronavirus.

Borrowing so far this year is at its highest level since monthly records began in 1993. The overall government deficit is still heading to its highest in peacetime. The actual amount of borrowing in October, at £22.3bn, was double last year’s amount, but less than the record months earlier this year during the pandemic. Spending on the furlough scheme, for example, was down, and tax receipts had begun by to recover.

But with the UK now back in lockdown, and wages schemes returning in full, the outlook for the public finances ahead of next week’s Spending Review remains tricky. Despite this, the chancellor will claim that there will not be a return to the austerity years for Government departments. That is a tricky balancing act. And will not come as much comfort to those facing a tough message on public sector pay restraint.

The chancellor said on Friday: “We’ve provided over £200bn of support to protect the economy, lives and livelihoods from the significant and far reaching impacts of coronavirus.

“This is the responsible thing to do, but it’s also clear that over time it’s right we ensure the public finances are put on a sustainable path.”

‘No time for cuts’

Dr Jonathan Gillham, chief economist at PwC, said people should not be “overly concerned” by the debt levels.

“The Bank of England has committed to buy another £150bn of public debt, the UK’s credit rating is relatively stable and borrowing remains cheap.

“ONS figures for October show interest on borrowing fell by £4.4bn compared to October last year.”

And Michael Hewson, at CMC Markets, said despite the high borrowing, this may not be the time to rein back spending.

“While it is entirely understandable for there to be a debate about these unprecedented levels of public borrowing, one has to question whether now is the right time to do it, given that we haven’t as yet defeated the virus, or even got a vaccine programme in place yet.

“It’s hard to imagine that there would have been similar conversations being had in 1940, when the country was one year into World War Two.”

Leave a comment