It’s hard to overstate the influence of pop star Robbie Williams at the height of his career. He dominated British music charts and tabloids—proving to be the ultimate entertainer both on and off the stage. Having left school without any qualifications, Williams was just 16-years-old in 1990 when he landed a spot in Take That, which went on to become one of the U.K.’s most successful boy bands. Fans were devastated when Williams left the group in 1995, after his bandmates and management took issue with his partying habits. They were even more bereft a year later, when the remaining four members of Take That announced the band was splitting. (The Samaritans set up a special helpline for the distraught fanbase, largely made up of teenage girls.) The phenomenon of Take That was arguably the 90s’ version of Beatlemania. The fans were “obsessive,” Williams notes.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

While the public fully expected Take That’s lead singer and songwriter Gary Barlow to become the breakout star after the band broke up, it was Williams who took center stage as a solo artist, thanks to his game-changing 1997 track “Angels.” The song elevated his career, cementing his front-man status and introducing him to a global audience (though his international appeal never quite took off in the United States). Williams was considered by many to be the bad boy of pop. A firm fixture in the tabloids, he was often pictured leaving parties in a bleary-eyed state. He had high-profile relationships with All Saints singer Nicole Appleton, who went on to marry Oasis’ Liam Gallagher, and Spice Girls’ Geri Halliwell. However, behind all of the hit singles, headlines, and bravado, Williams was struggling to find a sense of peace and purpose. Plagued by self-doubt, the former boybander battled addiction and depression.

Williams’ highest highs and lowest lows come into focus in the new Netflix documentary series Robbie Williams. Out Nov. 8, the series features the pop star taking viewers through his memories of his time in the spotlight.

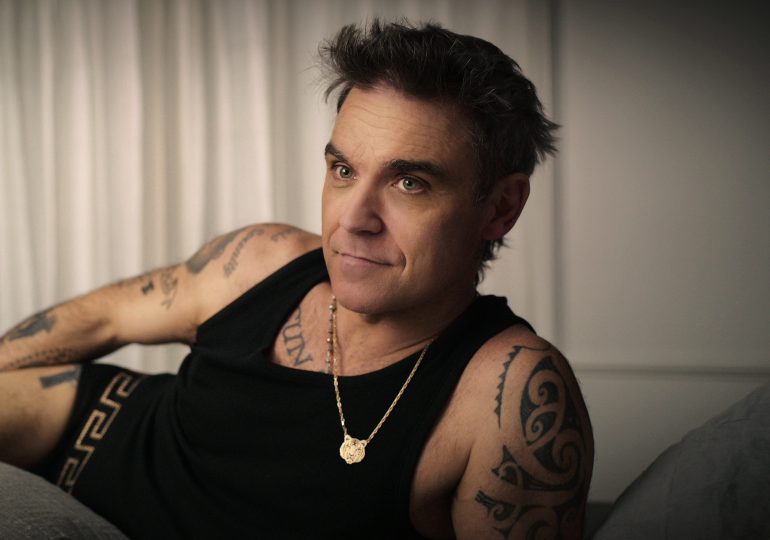

The four-part series, shot in 2022, takes us to Williams’ palatial Los Angeles home that he shares with his wife Ayda and their four children, who he heralds as being his saving grace. Aside from a few scenes where he’s pictured walking the grounds of his idyllic mansion in a Gucci cardigan, the singer spends the majority of the time lying in bed with his laptop, wearing a black vest top and briefs. “If I’m not on stage, I’m in bed,” Williams says, explaining the unorthodox location to director Joe Pearlman, the man behind other hit music documentaries such as Lewis Capaldi: How I’m Feeling Now. Williams watches behind-the-scenes footage and video blogs from his decades-long career, often grimacing as he’s confronted with moments he’s long sought to forget.

The “Let Me Entertain You” singer’s duality is prevalent throughout the documentary. He’s renowned for being an extrovert, yet admits he is “instinctively a loner.” He is often completely unguarded about his vulnerabilities. Reflecting on the era where his addiction to drugs and alcohol worsened, he reveals “there was a sense of… it would be best if I sort of passed away.” At other times, in the old footage especially, he comes off as arrogant and detached from reality. We witness Williams grapple with a desire to be “normal,” while acknowledging that he hasn’t truly lived a “normal” life since he was 16. “Nobody graduates from childhood fame well balanced,” the musician reasons.

Williams’ most conflicting relationships—with Take That, the British press, and with himself—form the crux of the story. Here’s what the documentary reveals about the most impactful relationships in his life and career.

Take That

In footage from the early ‘90s, Williams can be seen as an energetic teenager dancing alongside his bandmates. But the cracks soon started to show, as Williams rebelled against the polished image that had been created to represent the band. He also started to clash with lead singer Gary Barlow, who he felt was prioritized by the band’s management. Largely fueled by Williams, the rivalry went on for years. The singer often called out his former bandmate on stage and in interviews, sometimes going so far as to issue cruel jibes about Barlow’s appearance. In one moment of the documentary series, Williams looks back at footage from the ‘90s, as his daughter Teddy (born Theodora) makes one of her welcome interruptions. With the bluntness only a child can get away with, she quizzes her dad about his feelings on Take That, asking: “Who did you hate the most and why?” Without much hesitation, William admits: “I disliked Gary the most… I wanted to make him pay by having the career he was supposed to have.” He later confesses to feeling regret over how he treated Barlow during those years.

After reuniting in 2005, Take That pulled off an impressive comeback, topping the British charts once more and enjoying a critically-acclaimed tour. Williams, then at a low-point in his professional career, watched from afar. Although his memories from his early years in Take That had been “sullied” by how unhappy he was behind the scenes, he later yearned for that sense of brotherhood on stage. In 2009, when Williams battled with his mental health and low confidence as he attempted to make a solo comeback, he turned to his old bandmates. He rejoined the group for an album and a tour in 2010, before leaving once again in 2014. It was a full-circle moment for the singer, who had spent years actively separating himself from the “ex-boybander” label.

Guy Chambers

Take That’s split is not the only band break-up Williams encountered in his career. When the singer was struggling to find his solo voice in the industry, he teamed up with Guy Chambers, who became his musical director and co-writer. He refers to Chambers as one half of the “Robbie Williams band.” It’s easy to view Chambers as the Bernie Taupin to Williams’ Elton John. The duo collaborated on all of Williams’ biggest hits, including “Angels,” “Rock DJ,” “Millennium,” and “Let Me Entertain You.” Chambers features in much of the footage that Williams revisits in his documentary. Their friendship and brotherhood transcended beyond the studio, as we witness them traveling the world together. In Episode 2, during a prominent video filmed in 2000, the duo are seen enjoying a holiday in the South of France with their respective partners. Chambers is with his wife Emma, and Williams is with former Spice Girls member Geri Halliwell. Although we’ve already watched a whole episode’s worth of footage at this point, Williams admits that this holiday is the first time we’ve seen him truly happy.

But their harmonious bond fractured over time, and by 2002, Williams had decided that there was no longer a professional future for him and Chambers. “I needed full control, as much as possible,” he says, reflecting on his decision to cut Chambers from any future albums. “I was done with him.” Williams is cut-throat about the union ending, in an attitude that mirrors his reaction to his split from Take That and makes you wonder if, back then, he viewed people as disposable. It’s another instance of Williams’ dual nature, as he cherished the brotherly bond he shared with Chambers, yet desperately sought to prove that he could go it entirely alone.

The British press

Williams’ fractured, career-defining relationship with the British media is explored throughout the documentary. The invasive nature of the paparazzi, in particular, grated on Williams. Recalling his “confusing relationship” with Geri Halliwell, he says the intrusive nature of the press and the heightened interest in their union had a detrimental impact. Williams recalls being bewildered by how the paparazzi always managed to find them, noting that he was once informed by a photographer that Halliwell was orchestrating the paparazzi shots herself. Although Williams now says he doesn’t believe that to be true, he did at the time, and it wasn’t long before he and Halliwell parted ways.

“Robbie Williams is a crime against music” and “Robbie’s a loser” are just some of the brutal headlines revisited in the documentary. Among the historical footage, the singer can be seen phoning British tabloid newspaper The Sun to confront them over a “Stroppy Williams” story they had published. The singer’s push-and-pull relationship with the press reached its height in 2006, when he was lambasted for releasing a rap song, “Rudebox.” The change in direction was not well received, and Williams believes the British press’ poor reaction to the song negatively impacted the public and, in turn, his record sales.

In 1999, Williams tried to “break America” but was unsuccessful in his efforts. His “cheeky” British humor and his tendency to flash his bum on stage didn’t translate well with American audiences. At the time, this was a devastating loss to the record company who had invested so much in Williams’ attempt at success across the Atlantic. But Williams was later grateful for remaining a relative unknown in the U.S., reveling in regaining his anonymity when he moved to Los Angeles in the early 00s. Williams recalls being filled with a sense of dread when he returned to the U.K. on tour. “It represents hatred and a lack of safety,” he says. “I am divorced from the land that was once mine and I’m deeply, deeply affected by it.”

In spite of all this, Williams still craved the acceptance and approval of the British press. In footage from his 2009 comeback, he excitedly tells the camera that an article about his return to music is “number two on the BBC’s most read” stories. The media’s acceptance, and fame in general, appears to be another drug that Williams struggled to resist.

Addiction and mental health

Williams had a long and hard road battling addiction before getting sober during an ultimatum trip to rehab in 2007, organized by his increasingly concerned management who had witnessed him relapsing. “I’m a want monster, I want everything,” Williams states, before reeling off the drugs he used to indulge in or, as he calls them, his “greatest hits.” The singer’s addictions initially took a strong hold over him when he was 19. Newly divorced from Take That, Williams admits to “ingesting everything I could get my hands on.” As he jostled with the trauma brought about by transitioning from boyhood to manhood in front of the public’s glare, he soon came to rely on drugs and alcohol as a crutch.

In one enlightening moment, the singer recognises that the attributes that made him an addict are the same ones that made him a renowned showman. His “let’s see how far we can take this” attitude had both a positive and negative impact on his life and career.

Having been diagnosed with depression in his early 20s, Williams went on to experience what he describes as a “nervous, mental breakdown.” Although he was considered to be a cheeky chappy in the press, the musician struggled with depressive episodes which, at the height of his troubles, impacted his ability to perform, preventing him from doing the thing he believes he was born to do.

The man in the mirror

The experience of watching the Netflix documentary means seeing Williams get in his own way time and time again, a cycle revealed to be something only he could break. While the singer voices the impact of the press’ brutal criticism, it soon becomes apparent that Williams’ biggest critic is himself. Early on in the documentary, he alludes to his disordered eating. Reflecting on his first trip to rehab as a young twenty-something, Williams says the experience became more of a “weight loss camp” for him, admitting he was only eating a banana a day at the time. His body image issues are not directly brought up again, but they are visible in Williams’ self-loathing thoughts and taunts. Throughout the documentary, in both old and new footage, the singer refers to himself as “fat” and “fatty.” It’s always presented in a jovial, throwaway manner, but the sinister feeling behind it is clear for anyone who’s paying attention.

Over the years, Williams struggled with finding a sense of self-worth and purpose, at one point asking “am I enough?” He chased success, thinking it would amount to happiness, and although it worked for a short while, it wasn’t a sustainable or healthy way of living.

As the series shows, the singer managed to find some much-need balance after creating an identity outside of fame by becoming a father and husband. After meeting Ayda Field, a former American actor, in 2007, Williams embarked on a serious relationship with her after exiting rehab. “I guess the God-shaped hole has been filled with four kids and a wife,” he says in the closing moments of the documentary, sharing that he’s on his way to “being really, really happy.” Still very much a work in progress, like us all, Williams signs off the documentary from a place of hard-earned tranquility. Having confronted his darkest moments on tape, Williams has made peace with his former self and is focused on what the future holds.

Leave a comment