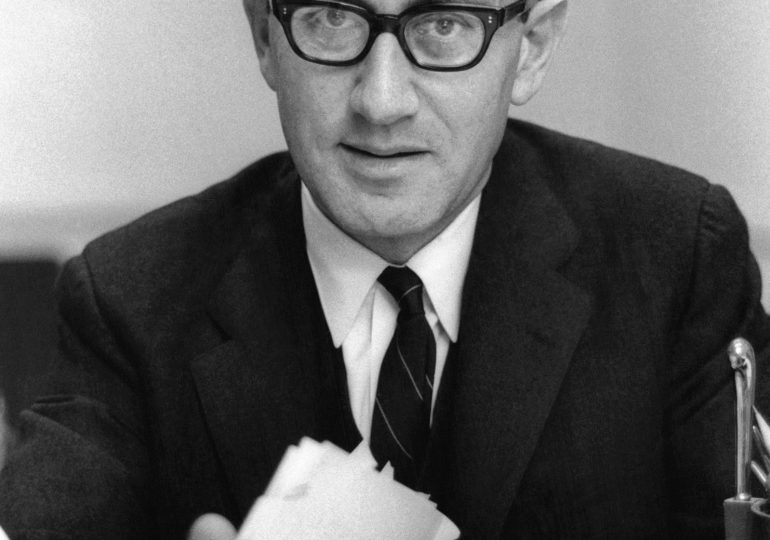

Henry Kissinger, the former Secretary of State known for his realist approach to foreign policy during the Nixon and Ford administrations, has died. He was 100.

News of his death was confirmed by a statement from his consulting firm.

Kissinger was a highly influential but polarizing figure. His impact extended beyond his tenure as national security adviser from 1969 to 1975 and overlapping/concurrent service as Secretary of State from 1973 to 1977, for decades spanning from the Vietnam War to the aftermath of 9/11. He leaves behind a mixed legacy: Once the most admired man in America according to a 1973 Gallup poll—the same year that he was controversially named the joint recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize for the Paris Peace Accords, along with North Vietnamese counterpart Le Duc Tho—he has also been fiercely criticized as a war criminal.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

As Secretary of State, he was known for pioneering a policy of détente with the Soviet Union and promoting an open door policy toward China. He’s also credited with eventually (some would argue belatedly) extricating America from the Vietnam War. But his critics have argued that his policies contributed to millions of deaths by permitting heavy bombing in Cambodia and Laos, blocking the ascension of a democratically elected leader in Chile, genocides in East Timor and Bangladesh and civil war in southern Africa.

Born in 1923 near Nuremberg, Germany, Heinz Alfred Kissinger and his Jewish family fled the Nazis in 1938. (Once in America, he changed his name to Henry.) As a new American citizen, he served in the U.S. Army for three years, returning to Europe to fight in World War II and receiving a Bronze Star in 1945. Kissinger then earned bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from Harvard, where he held a faculty appointment from 1954 to 1969.

Kissinger was one of the leading practitioners of realpolitik, arguing that pragmatism—rather than idealism—should govern America’s approach to foreign policy. He once famously said that “power is the ultimate aphrodisiac,” a mentality that manifested itself, some critics alleged, in a calculating and opportunistic approach to his professional relationships.

In the 1968 presidential election, Kissinger hedged his bets. After Nixon won the nomination, Kissinger—a former adviser to rival Republican Nelson Rockefeller, then Governor of New York—sent vague updates to the Nixon campaign about the status of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s peace talks with North Vietnam. But Kissinger played both sides: offering, but never ultimately delivering, Rockefeller’s opposition research on Nixon to Hubert Humphrey’s campaign.

Once Nixon appointed him national security adviser, Kissinger proved adept at navigating the administration’s atmosphere of suspicion and wiretaps, reportedly authorizing FBI investigations and wiretaps against at least one member of his staff and further knowledge of staff surveillance.

He managed to escape the Watergate scandal largely unscathed, continuing to serve as Secretary of State until the end of the Ford administration in 1977, when he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award.

After co-founding an international consulting firm, Kissinger Associates, Inc., in 1982, he continued to leverage his global connections and remain active in diplomatic circles.

Though he was no longer Secretary of State, he continued to advise future administrations. Reagan appointed him chair of the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, which he led from 1983 until 1985. He also served as a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board from 1984 to 1990.

In November 2002, President George W. Bush appointed Kissinger chairman of the 9/11 commission, but he resigned a few weeks later amid questions about potential conflicts of interest. Kissinger also served as a “powerful, largely invisible influence” on that administration’s approach to the Iraq War, according to Bob Woodward’s State of Denial. However, Kissinger tipped his hand a bit in a 2005 op-ed, writing that “victory over the insurgency is the only meaningful exit strategy.”

Kissinger’s influence also extended to another Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, who once wrote in The Washington Post that she “relied on his counsel.”

Some critics have objected to Kissinger’s continued involvement in American foreign policy, arguing that his actions as America’s top diplomat created long-lasting problems that the nation continues to grapple with today, such as aiding fundamentalist Islamic movements in the Middle East and playing a role in fostering American dependence on Saudi oil.

Nevertheless, Kissinger continued to remain active in both society and diplomatic circles well into his 90s. Continuing to meet with leaders from Russia and China, including at least 17 meetings with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. In June 2018, at the age of 95, he warned against the advent of artificial intelligence in a piece for The Atlantic entitled “How the Enlightenment Ends.” Two years later, in November 2020, Kissinger also warned incoming President Joe Biden to work quickly to restore U.S.-China relations that deteriorated during the Trump Administration.

But until the end, his political philosophy remained pragmatic. “America would not be true to itself if it abandoned [its] essential idealism,” he wrote in his book World Order at age 91. “But to be effective, these aspirational aspects of policy must be paired with an unsentimental analysis of underlying factors.”

Leave a comment